The Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) finalized new Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) regulations today, adopting two revisions from a comment that Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) proposed in January 2018. The FOIA allows for the disclosure of records of federal agencies, including documents, emails, and reports, and is an essential tool for promoting government transparency.

CoA Institute made three recommendations in response to the SEC’s proposed rulemaking. First, we urged the agency to remove outdated “organized and operated” language from its definition of “representative of the news media.” Such language has been used in the past to deny FOIA fee waivers to organizations like CoA Institute that investigate agency waste, fraudulent activity, cronyism, and wrongdoing. In 2015, we argued Cause of Action v. Federal Trade Commission before the D.C. Circuit, which resulted in a landmark ruling that invalidated the “organized and operated” requirement.

In Cause of Action, the D.C. Circuit clarified proper fee category definitions and the application of fees for FOIA requests. CoA Institute cited this case in its comment to the SEC and the agency concurred with our proposal to remove the outdated “organized and operated” language from its definition of a news media requester. The FTC also acknowledged the D.C. Circuit’s landmark decision in its final rule.

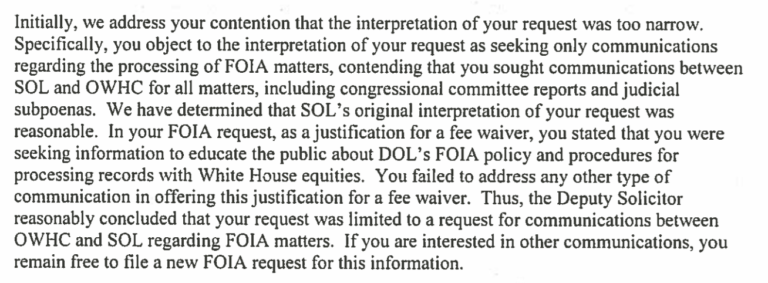

Second, CoA Institute recommended eliminating “case-by-case” fee category determinations. Under the original rule proposed by the SEC, FOIA offices would “determine whether to grant a requester news media status on a case-by-case basis based upon the requester’s intended use of the requested material.” CoA Institute again cited Cause of Action to argue that the focus of the fee waiver inquiry should be on “requesters, rather than [their] requests.” The SEC agreed and removed the restrictive language.

Finally, CoA Institute recommended that the SEC recognize that a news media requester may use “editorial skills” to turn “raw materials into a distinct work” when writing documents such as press releases and editorial comments. This understanding broadens the potential pool of news media requesters and our recommendation tracks language from the D.C. Circuit’s decision in Cause of Action. Although, in this respect, we did not recommend any specific changes to the final rule the SEC nevertheless acknowledged our comments by stating that it “will consider Cause of Action and any other relevant precedents in applying the fee provisions in its regulations.”

Americans have an interest in living free and prosperous lives without the interference of arbitrary and abusive executive power. One of the ways CoA Institute monitors government overreach is by fighting for access to information on the federal government’s activities. Our successful comment is a small but important victory in our work to ensure a transparent government that works for the benefit of all Americans.

Chris Klein is a Research Fellow at Cause of Action Institute