Last week, a group of eight Democratic Senators, led by Ranking Member Jon Tester of the U.S. Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, wrote to the Department of Veterans Affairs (“VA”) to express concern over the possible politicization of the agency’s Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) processes. The senators requested various records concerning the involvement of political appointees in the FOIA decision-making process, as well as other “sensitive review”-type policies. They also wrote to the VA’s Inspector General to request an investigation into these allegations. Among other things, the legislators sought “an assessment of the role that political appointees play in the FOIA process, what types of oversight exist to ensure employees are providing all responsive material, and who makes determinations about what is or is not responsive to a request[.]”

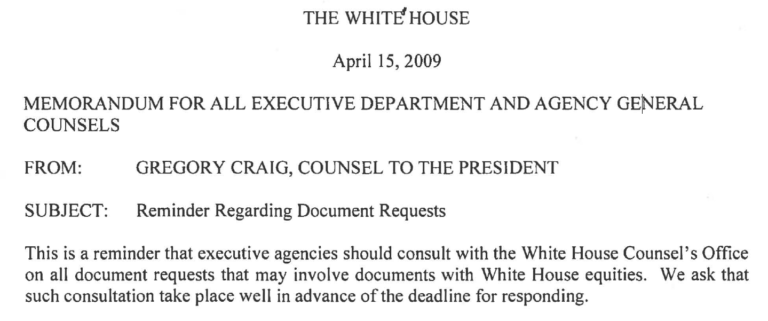

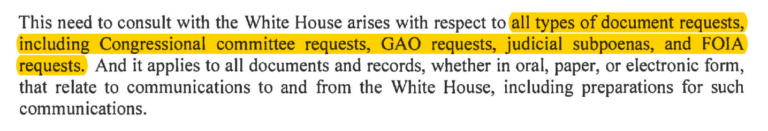

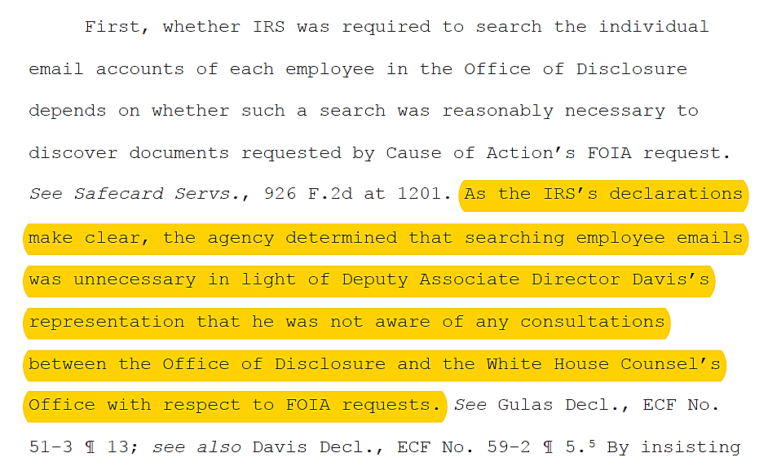

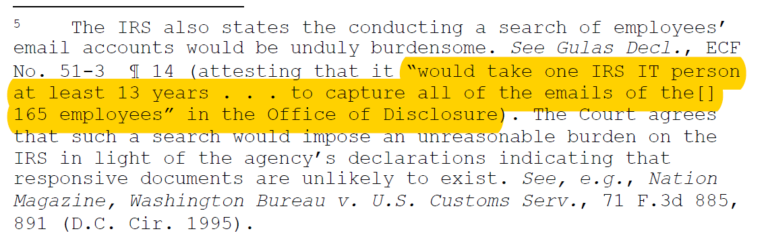

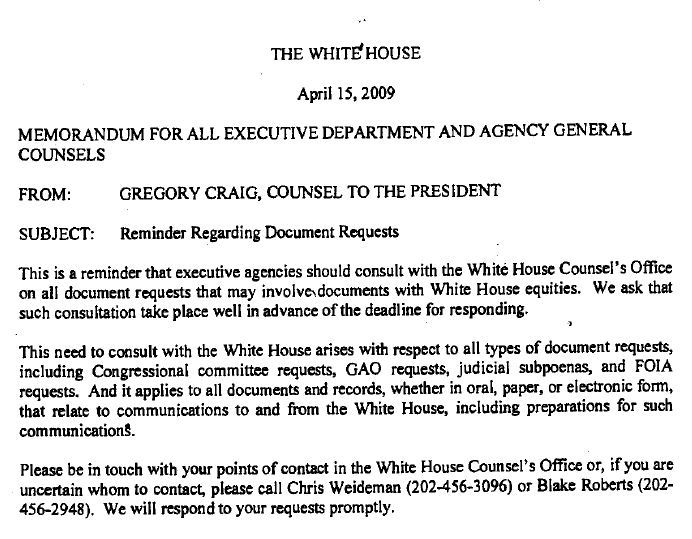

Sensitive FOIA review has been increasingly in the news. The most recent reports have focused on the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”). According to EPA Chief of Staff Ryan Jackson, the Trump Administration has added an “extra layer of review” for “politically charged” or “complex requests.” Other officials claim that “sensitive review,” and similar practices such as “White House equities” review, actually originated with the Obama White House. This latter claim is better supported by the historical record, as I (here and here) and others (here) have repeatedly argued. The Obama Administration was notorious for its efforts to delay and block the disclosure of politically damaging or otherwise newsworthy records. This is not to say the Trump Administration is innocent—it has likewise contributed to obfuscation and an overall erosion of transparency. My posts earlier this year on sensitive review at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Federal Aviation Administration demonstrate as much.

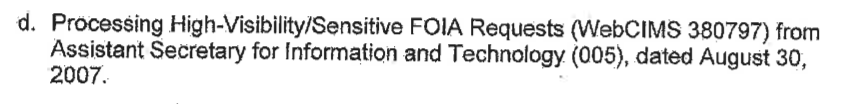

In the case of the VA, the agency’s watchdog previously argued, in 2010 and 2015, that there has not been regular inference by political appointees in the FOIA process. But the public has long known of internal practices at the VA that likely contribute to politicization. In August 2007, for example, the agency issued a directive concerning the processing of “high visibility” or “sensitive” FOIA requests that implicate potentially embarrassing or newsworthy records.

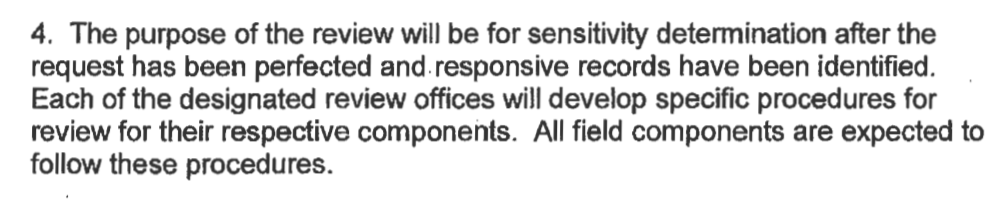

The potential for politicization only worsened during the Obama Administration. An October 2013 memorandum instructed all Central Office components to clear FOIA responses and productions through Jim Horan, Director of the VA FOIA Service. (Mr. Horan is still part of the leadership in the Office of Privacy and Records Management.) This clearance process imposed a “temporary requirement” for front office review—although it is unknown whether the practice continues—and entailed a “sensitivity determination” leading to unnamed “specific procedures.”

Regardless of which party or president controls the government, sensitive review raises serious concerns. Although alerting or involving political appointees in FOIA administration does not violate the law per se—and may, in rare cases, be appropriate—there is never any assurance that the practice will not lead to severe delays of months and even years. At its worst, sensitive FOIA review leads to intentionally inadequate searches, politicized document review, improper record redaction, and incomplete disclosure. When politically sensitive or potentially embarrassing records are at issue, politicians and bureaucrats will always have an incentive to err on the side of secrecy and non-disclosure.

Considering the new allegations of FOIA troubles at the VA, CoA Institute has submitted a FOIA request seeking further information about the agency’s sensitive review policy. We will continue to report on the matter as information becomes available.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.