Shortly after President Trump took office, Politico reported that a small group of career employees at the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) were using an encrypted messaging application, called “Signal,” to discuss ways to prevent incoming political appointees from implementing the Trump Administration’s policy agenda. The use of Signal at the EPA mirrored reports about the use of other electronic messaging platforms across the government.

Records recently released to CoA Institute under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) now confirm that a number of EPA employees installed Signal, WhatsApp, and at least sixteen other messaging applications on their agency-furnished devices. These records also reveal that EPA employees installed a panoply of other applications—including email, sports betting, dating, and entertainment applications—that raise questions about the use of government-issued and taxpayer-funded mobile devices for personal purposes.

CoA Institute’s Investigation of Messaging Apps at the EPA

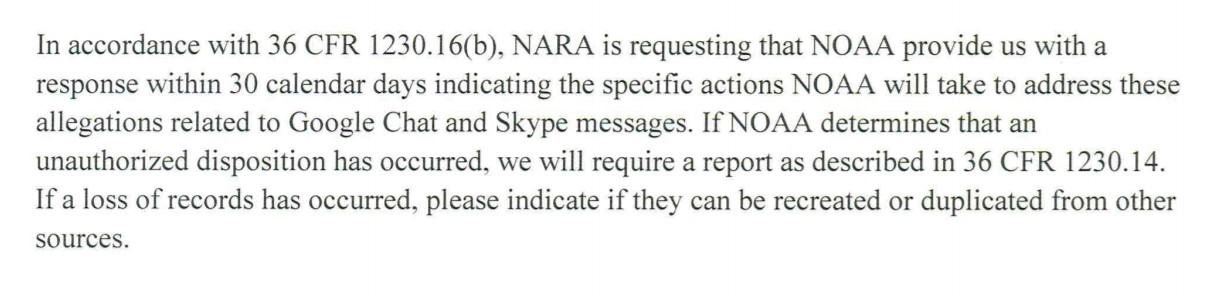

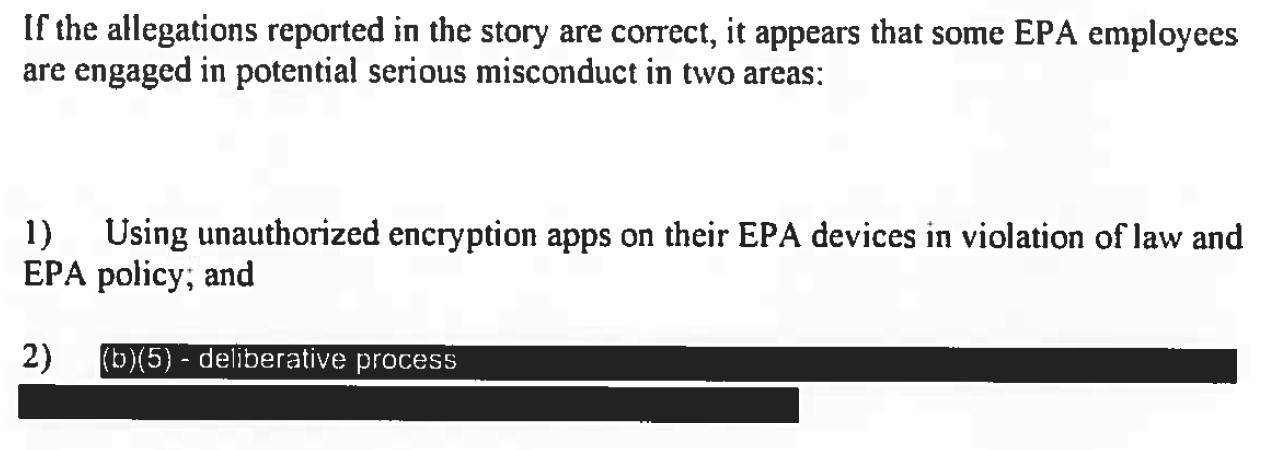

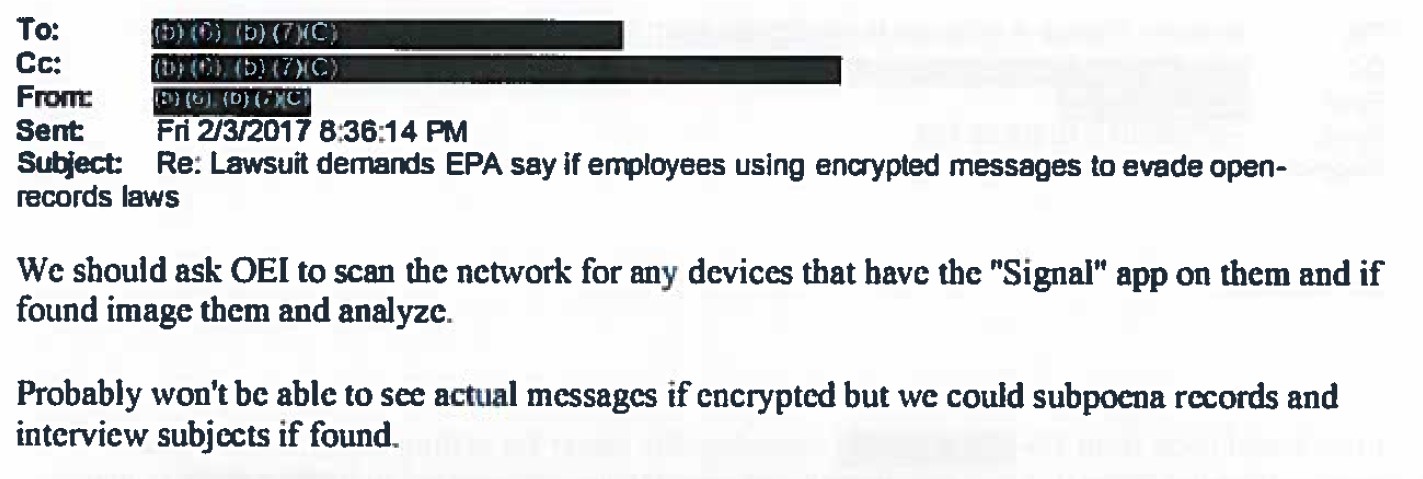

Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) opened its investigation into the use of Signal because we were concerned that the application might be used to conceal internal agency communications from oversight and to avoid EPA obligations under the FOIA and the Federal Records Act (“FRA”). We were not alone in our suspicions. After the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology’s requested that the EPA Inspector General analyze the allegations reported in the press, the National Archives and Records Administration (“NARA”) opened its own inquiry into the potential violation of federal records management laws. That inquiry remains open.

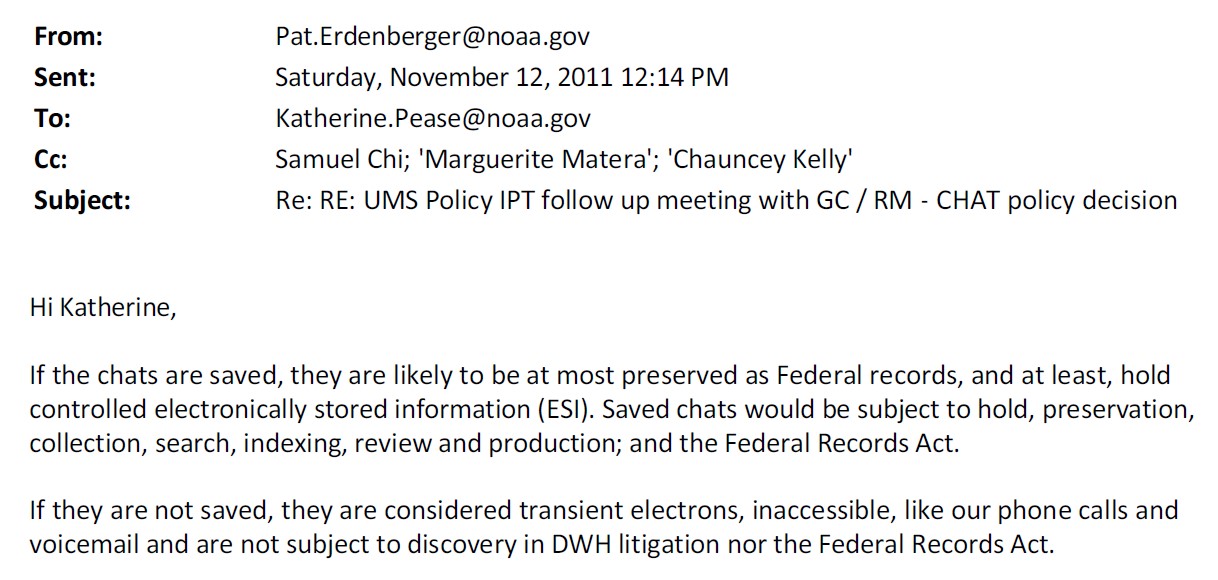

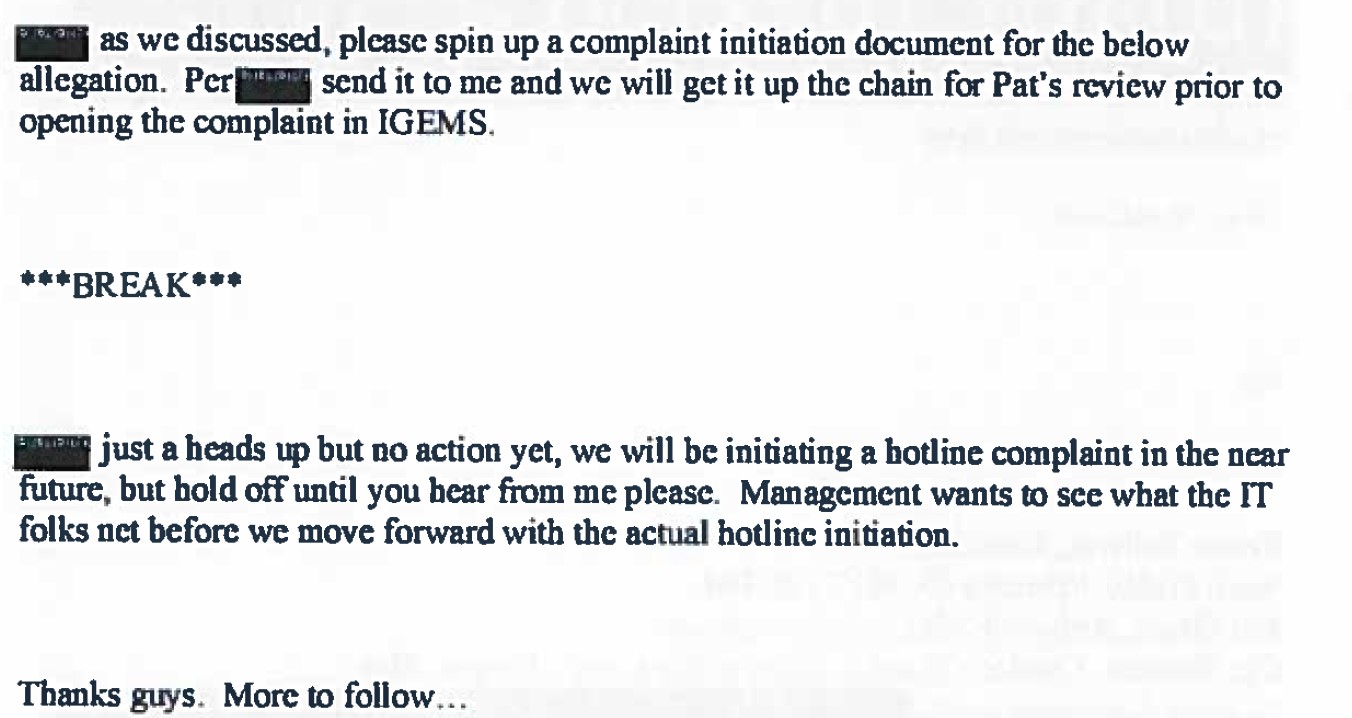

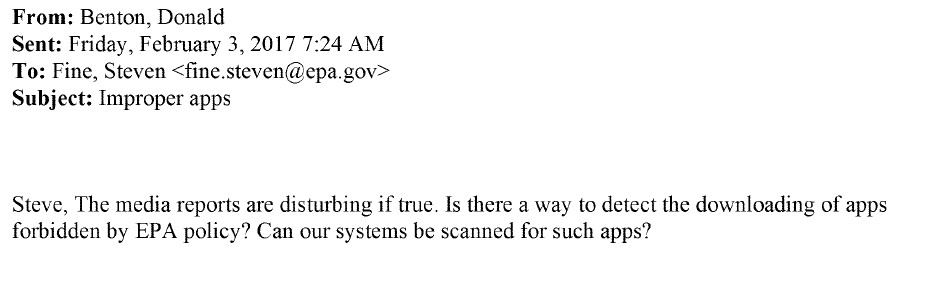

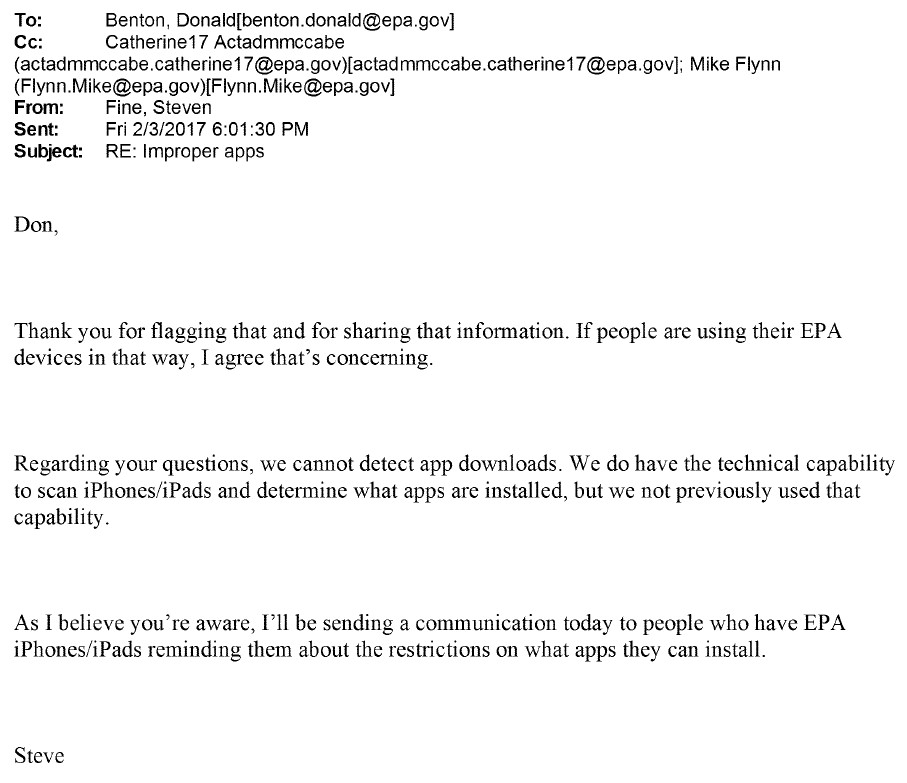

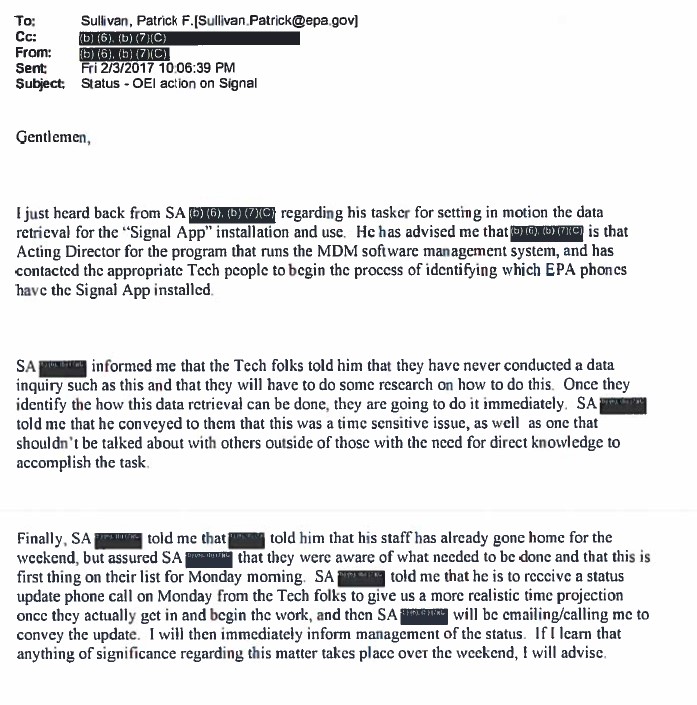

Over the past year we have slowly pieced together details about the Signal scandal. In response to our first FOIA lawsuit, the EPA acknowledged that there was an “open law enforcement” investigation. Although the EPA initially claimed that many records would be withheld in full, it changed its position and released records that corroborated the alarming facts reported by the media. But, as we have explained, the records also revealed much more. Among other things, they confirmed that CoA Institute’s original FOIA request, as reported by the Washington Times, was the actual impetus for the EPA Inspector General’s (“IG”) investigation. As Assistant Inspector General Patrick Sullivan noted at the time:

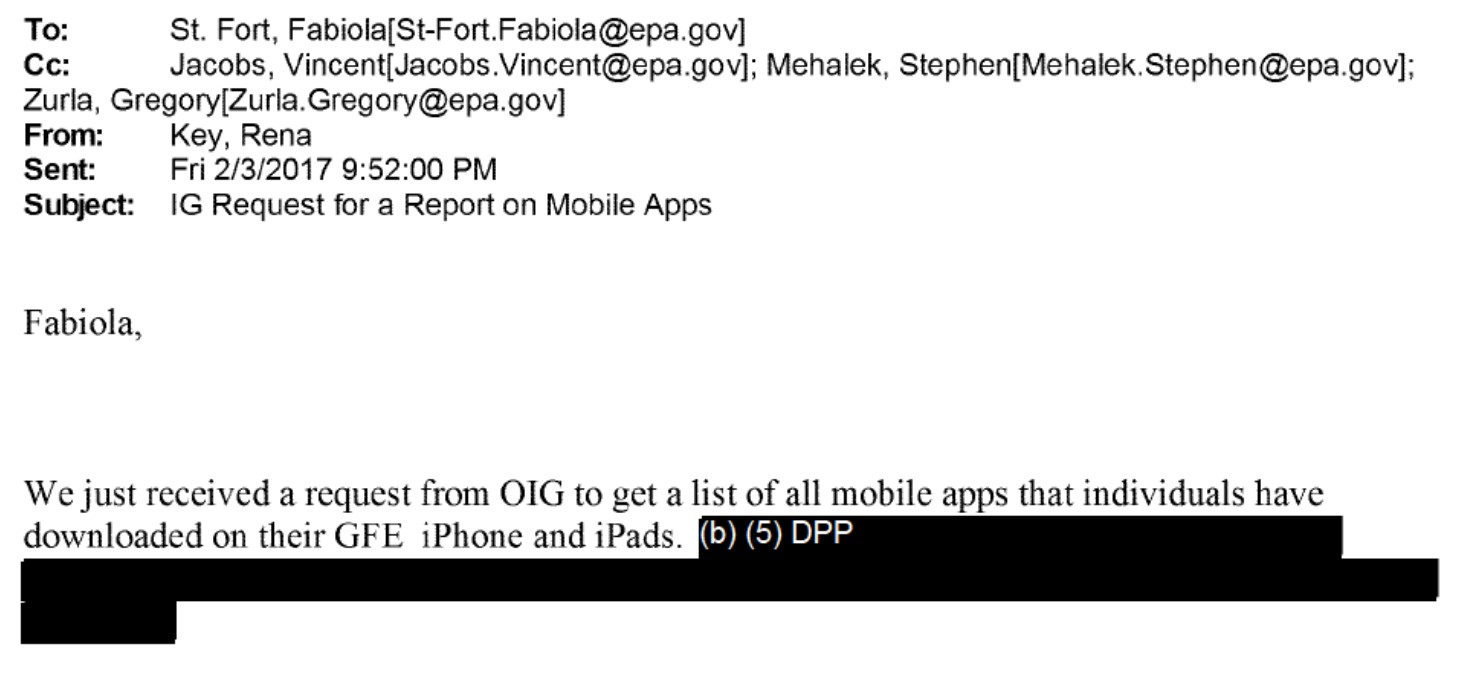

The records also confirmed that an EPA contractor “scanned” most agency-furnished devices for the different applications that had been installed by employees. This scan, which was requested by the IG, was conducted with a software tool known as “Mobile Device Management,” or “MDM.” As part CoA Institute’s second FOIA lawsuit, the EPA disclosed that contractor-generated report, as well as other documents.

The EPA IG’s Investigatory Conclusions on Signal

The EPA IG memorialized its findings about the Signal scandal in a series of investigatory memoranda. The watchdog determined that Signal was not used to “purposefully circumvent the applicable Federal record retention rules.” Nevertheless, it concluded that two employees—one in the Office of the Inspector General and the other in the Office of the Science Advisor—violated agency policy by downloading the unapproved application, as revealed by a summary of a subset of the MDM report.

In each instance, the IG interviewed the offending employee and consulted the Department of Justice before concluding that no “discernable crime” had been committed. The employee in the Office of Inspector General had downloaded Signal “to see if there was a suitable law enforcement purpose for the application.”

The employee in the Office of the Science Advisor denied having the application on his or her device, but consented to an examination of the phone. Although Signal “did not appear to be currently installed,” there was no final explanation for how the application originally found its way onto the phone. The IG opined that it could have happened due to unintentional synching with a personal Apple account.

But Maybe the Problem Was Never Signal . . .

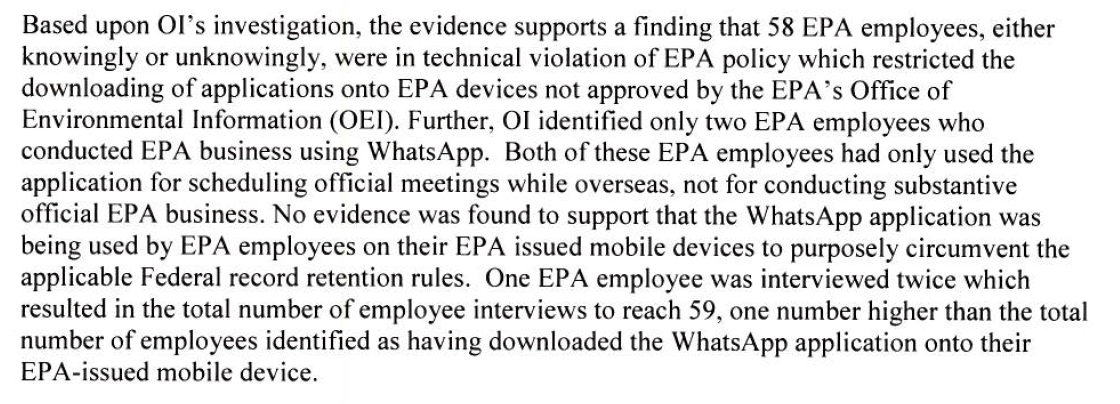

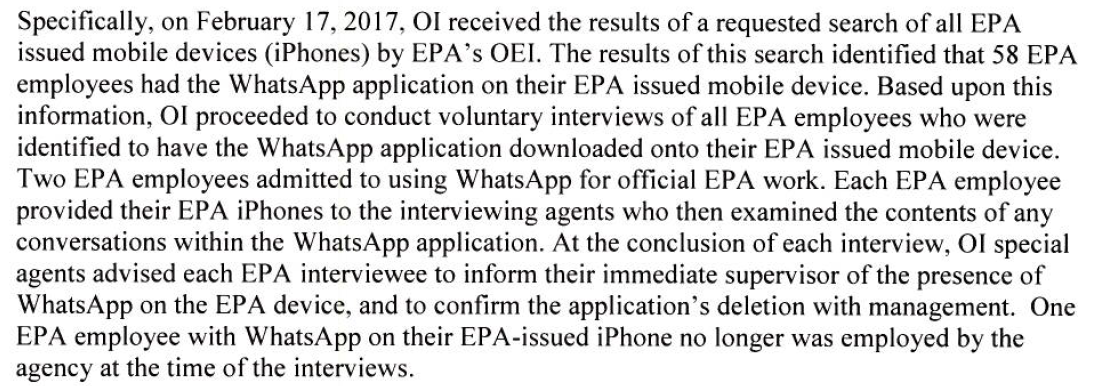

As exonerating as the IG’s conclusion may be, the story does not end there. While investigating the use of Signal, the EPA and the IG also discovered that fifty-eight employees violated official policy by downloading another encrypted messaging app, named “WhatsApp.”

The IG similarly determined that federal records laws had not been violated based on voluntary interviews of the fifty-eight employees, but this finding is somewhat contradicted by the admission of two employees that they used WhatsApp for “official EPA work.”

When all fifty-eight employees were polled on their “motivation and intent” for downloading WhatsApp, the clear majority cited a “lack of clarity” in the agency’s policy for not installing unapproved applications. More than half also suggested that they had downloaded WhatsApp for “the purpose of keeping in touch with family/friends domestically or overseas.”

A Potentially Serious Deficiency in the EPA IG’s Inquiry

When the EPA scanned the contents of most mobile devices during the Signal investigation, it also produced a summary of all the applications installed on agency-furnished devices, along with an “install count” for each program. The list runs ninety-six pages long and its contents are shocking.

To begin with, although the Signal scandal originally concerned the use of that single program, and was later expanded to include WhatsApp, the complete MDM report, which was released to CoA Institute, indicates that at least another sixteen applications with electronic messaging capabilities were being used by EPA employees. These applications—many of which are likely unapproved and raise the exact same FOIA and FRA concerns as Signal and WhatsApp—include:

AIM (1 phone)

BlackBerry Messenger (3 phones)

Facebook Messenger (227 phones)

Google Hangouts (27 phones)

GroupMe (10 phones)

Jabber (27 phones)

KakaoTalk (3 phones)

Kik (1 phone)

LINE (1 phone)

Skype (58 phones)

Slack (7 phones)

Snapchat (25 phones)

Telegram (1 phone)

Viber (19 phones)

WeChat (2 phones)

WickrMe (1 phone)

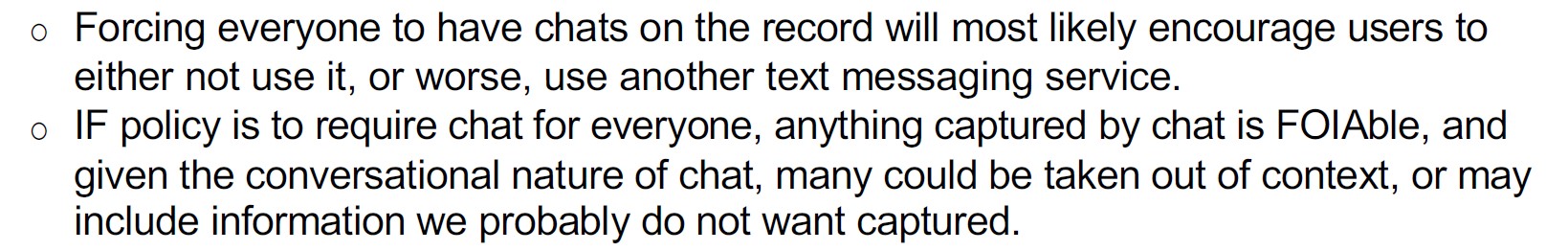

Why did the EPA IG fail to investigate these other applications, some of which are capable of encrypted messaging? Perhaps because the EPA’s Office of Environmental Information never handed over the full MDM report. This is suggested by two records.

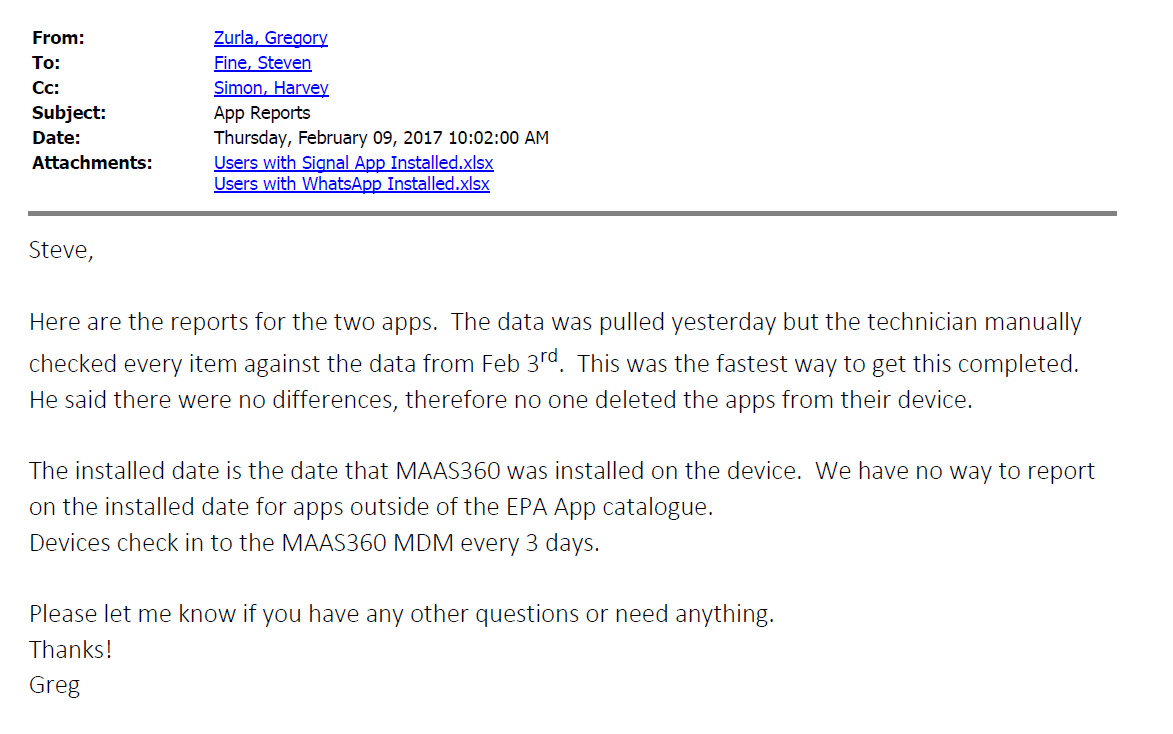

First, the EPA admitted to CoA Institute that it prepared two attachments (here and here) containing subsets of data from the MDM report, namely, those data that revealed the number and identifies of users with Signal or WhatsApp installed on their phones.

Second, the transmission of only the two summaries is suggested by the email referenced above, which also was disclosed to CoA Institute. An IT team leader, Greg Zurla, sent the heads of the Office of Environmental Information, Steven Fine and Harvey Simon, the data about Signal and WhatsApp, but nothing else. The IG’s final investigatory memoranda likewise reflect a targeted investigation into Signal and WhatsApp, with no mention of a broader dataset that could expose the unapproved use of similar encrypted messaging applications.

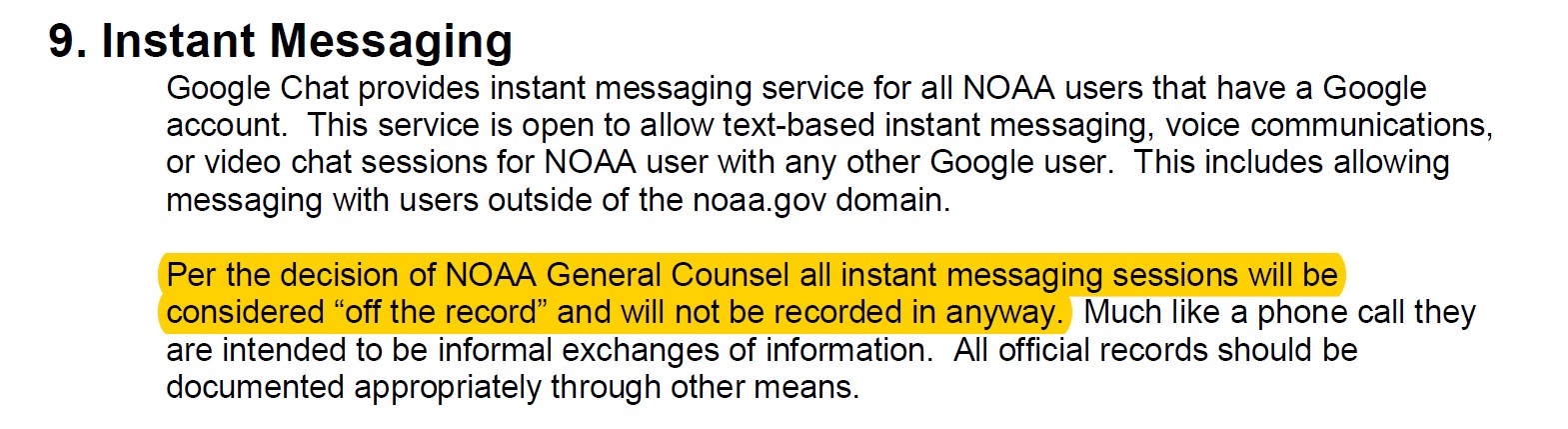

To the extent the IG was not—or still is not—aware of so many other messaging applications, then further inquiries need to be made. Whether these platforms were used for personal or work-related purposes, they are problematic and raise issues relating to federal records management. Moreover, although the IG has suggested that the EPA disabled the ability of some iPhone and iPad users to download the “Apple Store app,” and thus to install unauthorized applications, it is unknown whether all unapproved messaging applications have been deleted or, alternatively, whether adequate procedures have been put in place so that the EPA can meet all recordkeeping obligations.

The Use of Government Property for Personal Use is Deeply Troubling

The results of the IG investigation raise other troubling questions. Why should a government employee be able to justify his installation of an unapproved, and legally problematic, application on agency-furnished hardware by claiming that he wanted to use it for personal purposes? Should taxpayers pay for EPA employees to use government data plans to communicate with “family and friends”?

The full MDM report disturbingly reveals the sheer number of non-work-related applications that EPA employees installed. Some of these, such as web-based email programs, raise records management issues that have plagued other agencies like the Department of Homeland Security. The applications can be grouped into a number of categories. Here is a sampling:

- Web-Based Email

AOL (16 phones)

Gmail (129 phones)

Yahoo Mail (56 phones)

- Social Media

Facebook (466 phones)

Instagram (162 phones)

LinkedIn (117 phones)

Pinterest (75 phones)

Reddit (20 phones)

Twitter (310 phones)

- Dating

Coffee Meets Bagel (1 phone)

OK Cupid (1 phone)

- Personal Banking and Finance

AmEx (11 phones)

Barclaycard (6 phones)

Bank of America (29 phones)

CitiMobile (10 phones)

Wells Fargo (24 phones)

Navy Federal (11 phones)

PayPal (10 phones)

- Entertainment and Sports Betting

Angry Birds (14 phones)

Blackjack (5 phones)

Candy Crush (32 phones)

Draft Kings (1 phone)

Duolingo (10 phones)

ESPN (60 phones)

Fandango (15 phones)

HBO (15 phones)

Netflix (73 phones)

Pokémon GO (7 phones)

Shazam (22 phones)

SiriusXM (19 phones)

Spotify (71 phones)

YouTube (237 phones)

- Shopping

Amazon (56 phones)

eBay (16 phones)

- Religious

Bible apps (22 phones)

Catholic TV (1 phone)

- Political

Boycott Trump (1 phone)

Again, this is a non-exhaustive list. The full list can be accessed here.

Based on the EPA’s list of approved “Terms of Service” agreements, it appears that most of these applications were never authorized for work-related business. To the extent they were used for personal purposes, the EPA should take its workforce to task for abusing the privilege of a government-furnished and taxpayer-funded phone.

Although the IG reports that the EPA has disabled the Apple Store on newer models of the iPhone and iPad, we hope the agency makes serious efforts to remove these troubling applications from all makes and models of the hardware furnished to employees. Simply stated, the EPA does not exist so its bureaucrats can spend the day watching Netflix, browsing eBay, or swiping right on a dating application.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.