Some agencies have regulations that conflict with the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), which can lead to confusion for officials and the public, as well as the improper withholding of public information. For instance, a few agencies still base their definition of a “representative of the news media” on language that is outdated and contradicted by both the FOIA statute and judicial authorities. The old “organized and operated” standard that certain agencies have left in their regulations can be used to deny preferential fee treatment to nascent or non-traditional news media groups, as well as government watchdog organizations like Cause of Action Institute (CoA Institute). The current statutory definition, by contrast, is meant to broaden the universe of requesters qualifying for the news media fee category.

In Cause of Action v. Federal Trade Commission, a monumental decision in 2015 that resulted with an appellate court victory for Cause of Action Institute, the U.S Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit struck down the Federal Trade Commission’s outdated and narrow definition of a “representative of the news media” and confirmed the current statutory standard. The FTC had tried to deny CoA Institute its proper fee categorization and a public interest fee waiver.

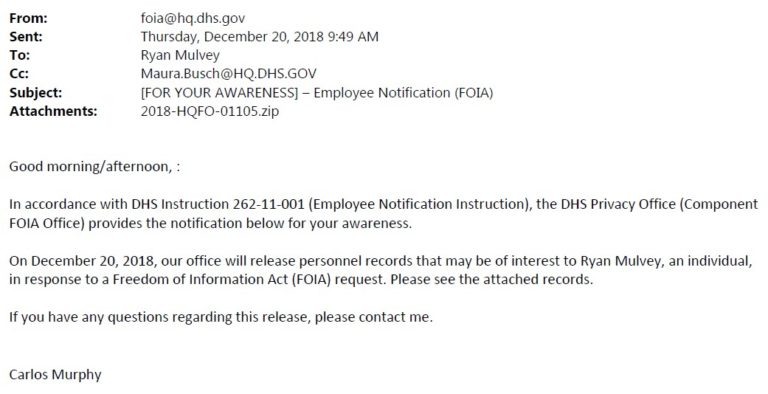

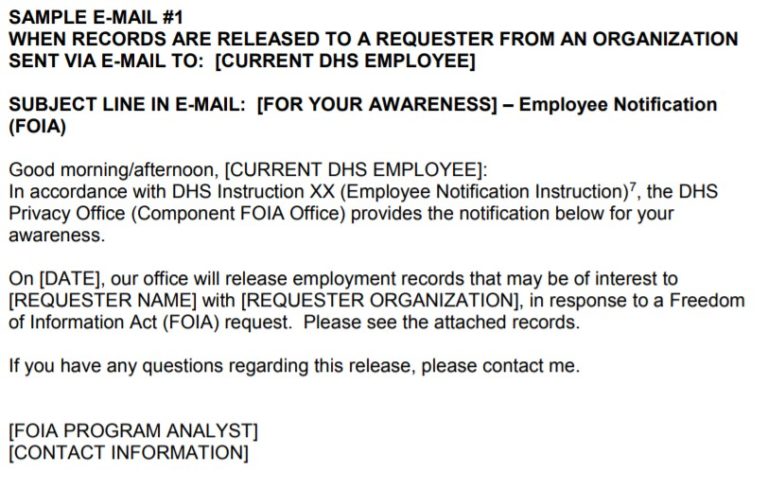

In March 2018, CoA Institute submitted a comment to the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), a small agency tasked with delivering foreign aid to combat global poverty, on the agency’s proposed rule revising its FOIA regulations. Among other things, CoA Institute suggested that the MCC correct its definition of a “representative of the news media.” In July of that year, MCC finalized a rule implementing the recommended revisions and taking a step towards effective and transparent oversight. CoA Institute has had similar success with FOIA reform at other agencies, including the Consumer Product Safety Commission, Office of the Special Counsel, U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Agency for International Development, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

This is but one example of the work CoA Institute performs to advance government transparency and protect the rights of the American public, taxpayers and our collective ability to hold our government accountable for its actions.

Matt Frendewey is Director of Communications at Cause of Action Institute.