Last week, a report from Politico revealed that the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) maintains a burdensome “sensitive review” process for Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) requests concerning Administrator Scott Pruitt’s activities. According to internal sources, officials within the Office of the Administrator have “reviewed documents collected for most or all FOIA requests regarding [Pruitt’s] activities[.]” The Politico report further claims that this “high-level vetting” has increased, as compared with the policies and practices introduced during the Obama years. “This does look like the most burdensome review process that I’ve seen documented,” argued Nate Jones from National Security Archive.

It is true that the Trump Administration has enhanced sensitive review processes at the EPA. Other agencies have witnessed a similar expansion of sensitive review, as Cause of Action Institute’s investigation of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration demonstrates. But it would be a mistake—as I argued last December—to think that the Obama White House was any better at avoiding FOIA politicization. The EPA has a long and terrible track record for anti-transparency behavior. Consider the agency’s blatant weaponization of fee waivers. According to data compiled by the Competitive Enterprise Institute, and reported by Reason and The Washington Examiner, the Obama EPA regularly denied public interest fee waivers to organizations critical of the agency’s regulatory activities and the White House’s policy agenda. By contrast, left-leaning groups nearly always (92% of the time) received fee waivers.

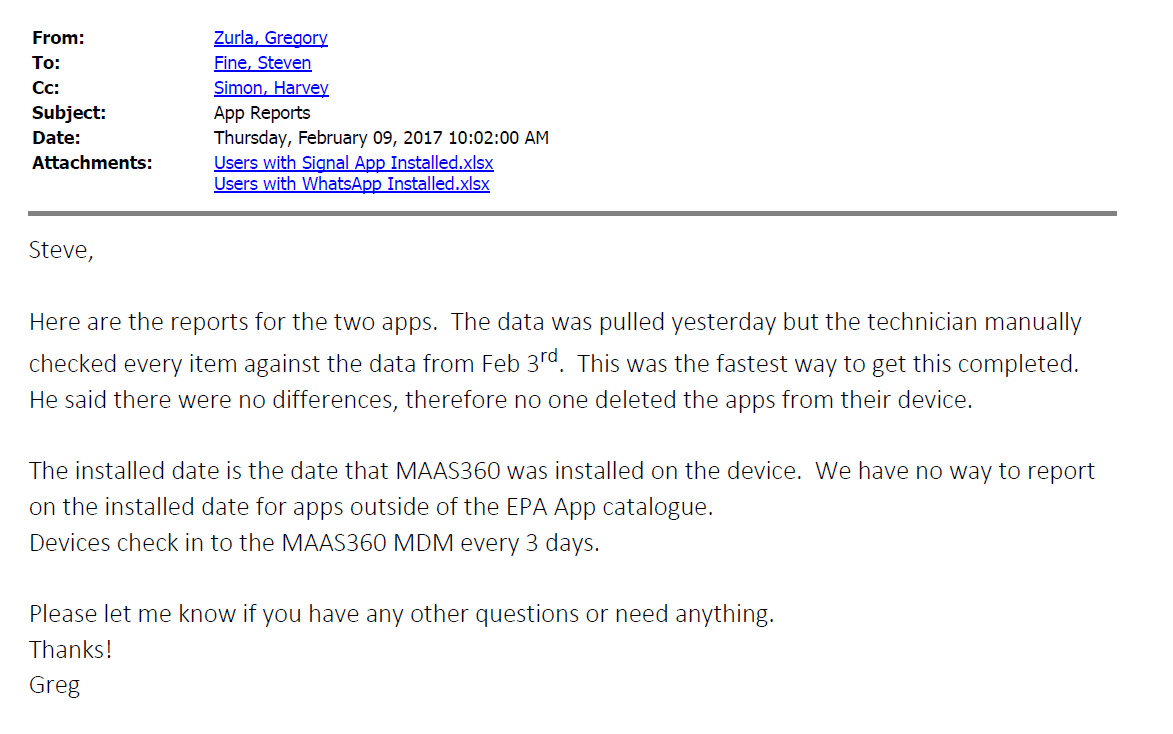

In addition to this viewpoint discrimination, the EPA suffered other transparency scandals. Former Administrator Lisa Jackson infamously used a fictional alter ego—“Richard Windsor”—to conduct agency business on an undisclosed government email account. And the EPA “misplaced” over 5,000 text messages sent or received by former Administrator Gina McCarthy and other top officials. The Obama-era EPA also tolerated the widespread use of personal email accounts by high-ranking bureaucrats, a practice that significantly frustrated public access to agency records and proved to foreshadow or parallel other FOIA scandals at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, the Department of Defense, and Department of Homeland Security, the Internal Revenue Service, and, most famously, the State Department. It is noteworthy that, in March of 2015, The Guardian—hardly a right-leaning paper—could seriously ponder: “Is the EPA having a transparency crisis?”

The history speaks for itself: the EPA under Scott Pruitt is not a new or unique threat to transparent government. The litany of FOIA abuses at the EPA and other agencies under both Presidents Obama and Trump demonstrate that we should fight the tendency to view the problem of FOIA politicization through a partisan lens. “Sensitive review” matured as a practice in the Obama Administration, and is continuing under President Trump, but there are institutional motivations for any and all bureaucrats, regardless of party affiliation, to frustrate the disclosure of records, particularly if they are embarrassing or raise the specter of media attention.

According to EPA Inspector General reports published in August 2015 and January 2011, the EPA’s FOIA regulations allow political appointees—including the Chief FOIA Officer and authorized disclosure official in the Office of the Administrator—to participate in approving requests and redacting records. Is it any wonder that an agency follows its own long-established rules for processing requests it deems “sensitive”? So long as the law gives the agency an opportunity to violate the spirit of the FOIA, the agency will take advantage of that discretion, even if it means violating statutory timelines for responding to requesters.

When Administrator Pruitt directed his staff to involve itself with the disclosure of records, he continued a tradition of obstructing the public’s right to access government information. He deserves the criticism he has received. But focusing on Administrator Pruitt’s (or President Trump’s) regulatory agenda, or his personal views on hot-button topics like global warming, obscures the underlying problem and makes it more difficult to reach consensus on how to address the real issues. The FOIA and implementing regulations, for one, need to prohibit “sensitive review,” or at least provide serious restrictions on its implementation. And guidance from the Department of Justice should address the troubling aspects that sensitive review can present. This should be part of a solution that everyone who believes in transparency can accept.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute