Cause of Action Institute (CoA Institute) received an interim response yesterday from the General Services Administration (GSA) on a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request that suggests the agency is deliberately stonewalling the release of a White House directive instructing agencies on how to respond to congressional oversight requests. Records released by the agency also suggest that the GSA has implemented a “sensitive review” FOIA process by which news media requesters are subject to an extra layer of pre-production review.

CoA Institute Discovers Curious DHS FOIA Notification Process for Employee Records

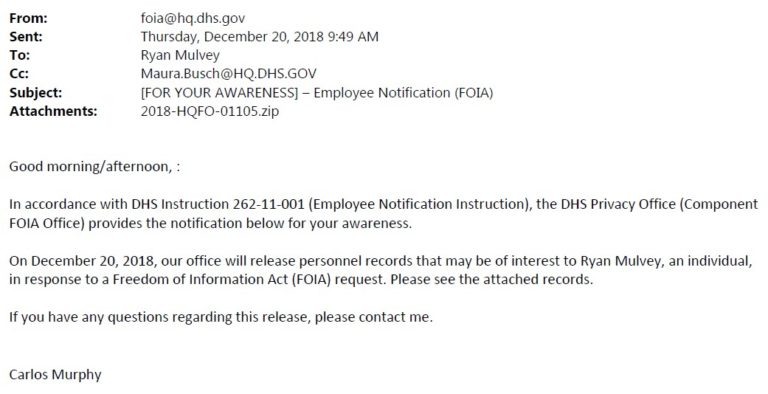

Earlier today, Cause of Action Institute (CoA Institute) received a misdirected email from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that apparently was intended to serve as a notification to an unidentified agency employee that certain personnel records were to be released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

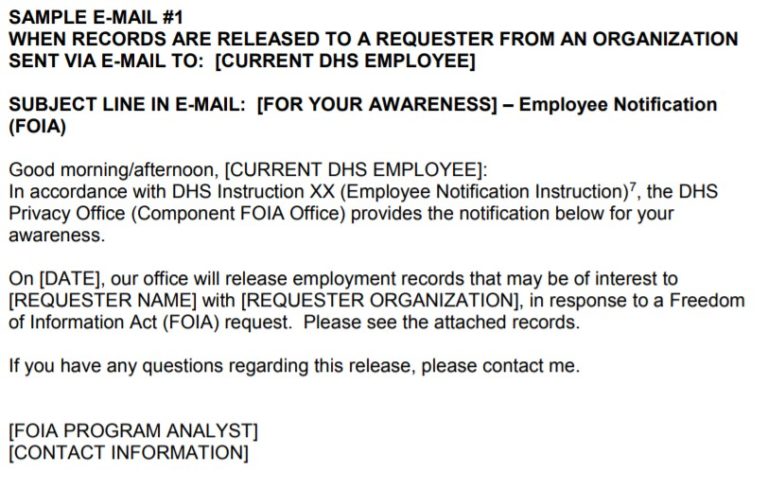

The “awareness” email indicated that employee-related records were scheduled to be released in response to a FOIA request. It also identified the name of the FOIA requester—a CoA Institute employee—and included an attached file containing the records at issue. The email was issued “[i]n accordance with DHS Instruction 262-11-001,” which is publicly available on the DHS’s website and appears to have been first issued at the end of February 2018.

Under Instruction 262-11-001, the DHS is required to “inform current [agency] employees when their employment records . . . are about to be released under the FOIA.” “Employment records” is defined broadly to include any “[p]ast and present personnel information,” and could include any record containing personal information (e.g., name, position title, salary rates, etc.). Copies of records also are provided as a courtesy to the employee.

The DHS instruction does not attempt to broaden the scope of Exemption 6, and it recognizes that federal employees generally have no expectation of privacy in their personnel records. More importantly, the policy prohibits employees from interjecting themselves into the FOIA process. This sort of inappropriate involvement has occurred at DHS and other agencies in the past under the guise of “sensitive review,” particularly whenever politically sensitive records have been at issue.

Nevertheless, the DHS “awareness” policy still raises good government concerns. As set forth in the sample notices appended to the instruction, agency employees are routinely provided copies of responsive records scheduled for release, as well as the names and institutional affiliations of the requesters who will be receiving those records.

To be sure, FOIA requesters typically have no expectation of privacy in their identities, and FOIA requests themselves are public records subject to disclosure. There are some exceptions. The D.C. Circuit recently accepted the Internal Revenue Service’s argument that requester names and affiliations could be withheld under Exemption 3, in conjunction with I.R.C. § 6103. Other agencies, which post FOIA logs online, only release tracking numbers or the subjects of requests. In those cases, a formal FOIA request is required to obtain personally identifying information.

Regardless of whether the DHS policy is lawful, it is questionable as a matter of best practice. Proactively sending records and requester information to agency employees could open the door to abuse and retaliation, particularly if an employee works in an influential position or if a requester is a member of the news media. The broad definition of “employee record” also raises questions about the breadth of implementation.

Finally, there are issues of fairness and efficiency. If an agency employee knows that his records are going to be released, is it fair to proactively disclose details about the requester immediately and without requiring the employee to file his own FOIA request and wait in line like anyone else? The public often waits months for the information being given to employees as a matter of course, even though the agency admits that there are no cognizable employee privacy interests at stake.

More importantly, an agency-wide process of identifying employees whose equities are implicated in records and individually notifying them about the release of their personal details likely requires a significant investment of agency resources. Would it not be more responsible to spend those resources on improving transparency to the public at large? To reducing agency FOIA backlogs? Notifying employees whenever their information is released to the public is likely only to contribute to a culture of secrecy and a further breakdown in the trust between the administrative state and the public.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute

Investigation Update: VA releases 2014 memo on “sensitive review,” but fails to conduct an adequate search for more recent FOIA guidance

- In August 2018, a group of eight Democratic Senators, wrote to the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to express alarm over the possible politicization of the agency’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) processes. Specifically, they were concerned about the involvement of political appointees in the FOIA decision-making process.

- Cause of Action Institute (CoA Institute) submitted a FOIA request to the VA seeking records about the agency’s “sensitive review” process, but the agency only disclosed a single document. After considering CoA Institute’s appeal, the VA Office of General Counsel ordered supplemental searches for additional records.

- “Sensitive review” raises serious transparency concerns because the involvement of political appointees in FOIA administrative can lead to severe delays and, at worst, improper record redaction and incomplete disclosure.

- Whenever politically sensitive or potentially embarrassing records are at issue, politicians and bureaucrats will have an incentive to enforce secrecy and non-disclosure.

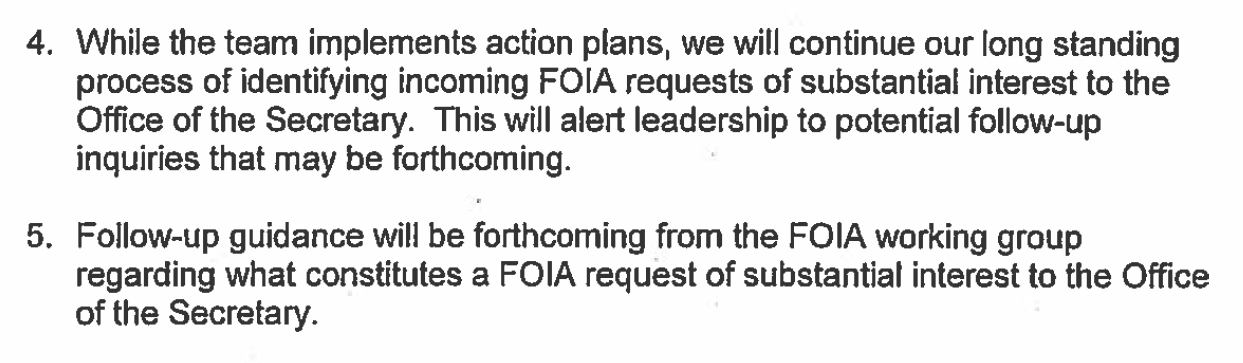

Earlier this year, CoA Institute opened an investigation into the sensitive review process at the VA. As I mentioned in an earlier post, the public has long been aware of internal practices at the agency that could open the door to FOIA abuse. During the Bush Administration, the VA issued a directive concerning the processing of “high visibility” or “sensitive” requests that implicated potentially embarrassing or newsworthy records. The Obama White House subsequently updated that guidance in October 2013, when the VA instructed its departmental components to clear FOIA responses and productions through a centralized office. This clearance process imposed a “temporary requirement” for front office review and entailed a “sensitivity determination” leading to unnamed “specific procedures.”

Another record recently disclosed to CoA Institute illustrates how the VA again updated its sensitive review process in February 2014. According to the memorandum, the agency intended to continue its “long standing” procedure for notifying leadership of incoming FOIA requests that may be “substantial interest to the Office of the Secretary.” Exact guidance on the sorts of requests that would trigger such review, however, was still under development at the time. It is unknown how the notification process was implemented in the absence of that guidance.

To date, the VA has failed to disclose any further records about sensitive review. CoA Institute successfully appealed the Office of the Secretary’s final response, and the agency’s Office of General Counsel ordered additional searches on remand. A precise deadline for a supplemental response was not given, but we will provide updates as any additional records become available.

To date, the VA has failed to disclose any further records about sensitive review. CoA Institute successfully appealed the Office of the Secretary’s final response, and the agency’s Office of General Counsel ordered additional searches on remand. A precise deadline for a supplemental response was not given, but we will provide updates as any additional records become available.

In light of its commitment to open government, CoA Institute has been a leader in examining cases of sensitive review at other agencies, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Federal Aviation Administration. We also have analyzed the practice at the Environmental Protection Agency on several occasions (here, here, and here). A recent press report concerning the EPA confirmed our warnings about the potential for delay when “sensitive” or politically charged records are targeted for special processing.

Regardless of which party or president controls the government, sensitive review poses a serious threat to government transparency. Alerting or involving political appointees in FOIA administration can lead to severe delays and, at its worst, contribute to intentionally inadequate searches, politicized document review, improper record redaction, and incomplete disclosure.

Loading...

Loading...

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.

____________________________________________________________

Media Contact: Matt Frendewey, matt.frendewey@causeofaction.org | 202-699-2018

Department of Veterans Affairs Discloses 2014 Guidance on Intra-Agency Consultations for FOIA Requests of “Substantial Interest” to Agency Leadership

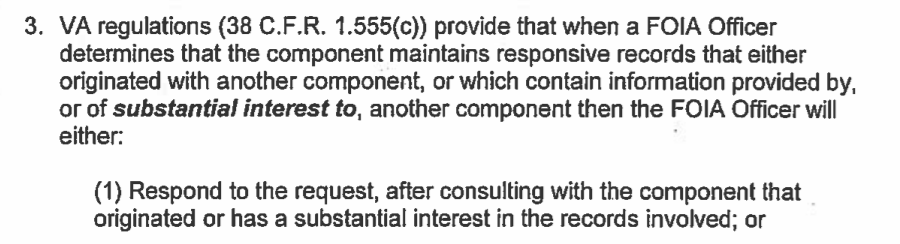

The Department of Veterans Affairs (“VA”) has released a February 2014 memorandum reiterating the need for “consultations” on certain Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) requests, including those of “substantial interest” to the agency’s political leadership. Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) obtained the record after submitting a disclosure request in the wake of Senate Democrats expressing concern over possible politicization of VA FOIA processes.

The memorandum, which is addressed to “Under Secretaries, Assistant Secretaries, and Other Key Officials,” indicates that VA regulations require intra-agency consultation or referral whenever incoming FOIA requests implicate records that originate with another component or prove to contain “information” of “substantial interest” to another VA office. While “referral” entails the effective transfer of responsibility for responding to a request, “consultation” refers to discussing the release of particular records.

Consultation within an agency or with other entities can be a positive practice that ensures records are processed in accordance with the law. Indeed, in some cases, “consultation” is required. Executive Order 12600, for example, requires an agency to contact a company whenever a requester seeks confidential commercial information potentially exempt under Exemption 4. Yet consultations occur in less-easily defined situations, too.

The FOIA only mentions “consultation” in the context of defining the “unusual circumstances” that permit an agency to extend its response deadline by ten working days.

[“Unusual circumstances” include] the need for consultation, which shall be conducted with all practicable speed, with another agency having a substantial interest in the determination of the request or among two or more components of the agency having substantial subject-matter interest therein.

Unfortunately, the phrase “substantial interest” is not itself defined. This is where problems begin. The Department of Justice’s (“DOJ”) guidance on consultation suggests that a “substantial interest” only exists when records either “originate[] with another agency” or contain “information that is of interest to another agency or component.” The DOJ’s FOIA regulations, and the Office of Information Policy’s model FOIA regulation, while not dispositive, do provide a little more context. They suggest “consultation” should be limited to cases when another agency (or agency component) originated a record or is “better able to determine whether the record is exempt from disclosure.”

CoA Institute has long sought clarification on the exact nature of a “substantial interest.” In November 2014, we submitted a public comment to the Department of Defense (“DOD”) arguing that consultation should be restricted to situations where another entity has created a responsive record or is “better positioned to judge the proper application of the FOIA exemptions, given the circumstances of the request or its familiarity with the facts necessary to judge the proper withholding of exempt material.” Although our proposed definition was admittedly non-ideal—DOD did not accept that portion of our comment—it hinted at the troubling abuse, politicization, and unjustifiable delay that can occur with consultation.

The best example of such abuse and politicization is found with “White House equities” review, which is carried-out as a form of “consultation.” As CoA Institute has repeatedly documented, however, this form of “consultation” extends far beyond “White House-originated” records or records containing information privileged by White House-controlled privileges. Instead, pre-production White House review has been extended to almost anything that is potentially embarrassing or politically damaging to the President. In May 2016, CoA Institute sued eleven agencies and the Office of the White House Counsel in an effort to enjoin the Obama Administration from continuing “White House equities” review, but that lawsuit was dismissed. It is unclear to what extent President Trump has continued the practice, although at least one other oversight group has uncovered evidence of recent White House review of politically sensitive records from the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

As for the VA, the recently disclosed memorandum is silent about the precise meaning of a “substantial interest.” But, at least for the “substantial interest” of the agency’s political leadership, the memorandum indicated that “[f]ollow-up guidance will be forthcoming.”

This is especially troubling. Last week, I discussed how DOD failed to address Inspector General recommendations concerning the agency’s so-called “situational awareness” process for notifying political leadership about “significant” FOIA requests that may “generate media interest” or be of “potential interest” to DOD leadership. I noted that agencies hide behind technical phrases—like “substantial interest” or “situational awareness”—while allowing non-career officials to inappropriately interfere with FOIA processes. This could be what is happening with the VA. Why is special “guidance” needed to identify the “substantial interest” that the VA Secretary may have in a specific request? Does this not hint of the same sort of inappropriate “sensitive” review implemented at countless other agencies?

CoA Institute has appealed the VA Office of the Secretary’s response. The 2014 memorandum was the only record produced in response to our FOIA request. The “follow-up guidance” should also have been located and disclosed. It must be made public. Other VA offices are still processing portions of our request; the Office of Inspector General, for its part, was unable to locate records about recent investigations into FOIA politicization. As further information becomes available, we will post additional updates.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute

EPA responds to House OGR Democrats, arguing FOIA “sensitive review” originated with the Obama Administration

Earlier this week, Democrats on the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee (“OGR”) released details about how officials from the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) admitted to subjecting politically sensitive Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) requests to layers of extra scrutiny, including review by political appointees. OGR Ranking Member Elijah Cummings even asked Chairman Trey Gowdy to issue a subpoena compelling the EPA to hand over various records documenting its FOIA processes.

Since Cause of Action Institute’s (“CoA Institute’s) coverage of this issue on Monday, there have been two important developments. First, on Tuesday, Chairman Gowdy denied OGR Democrats their request for a subpoena. Second, and more importantly, reports have revealed that Kevin Minoli, the EPA Principal Deputy General Counsel and Designated Agency Ethics Official, sent a letter to OGR Democrats on Sunday, arguing that the agency’s sensitive review policies actually originated with the Obama Administration.

According to Minoli, the EPA created a “FOIA Expert Assistance Team,” or “FEAT,” in 2013 to provide “strategic direction and project management assistance” on “complex FOIA requests.” Minoli explained that a FOIA request could be classified as “complex,” for FEAT purposes, if someone in the agency’s leadership requested it to be so. FEAT coordinated “White House equities” review and also alerted the Office of Public Affairs, as well as “senior leaders” within the EPA, of particularly noteworthy requests through its so-called “awareness review” process.

The EPA’s latest clarification vindicates CoA Institute’s repeated warnings (here and here) not to let political judgments about the Trump EPA’s policy agenda interfere with understanding and criticism of long-standing problems of FOIA administration, including the politicization that inevitably results from “sensitive review” processes. To be sure, it appears the Trump Administration has worsened the problem, particularly at the EPA. But the groundwork for this sort of FOIA politicization was laid by President Obama. Indeed, Minoli claims OGR’s investigative work during the Obama-era was part of the then-Administration’s impetus for creating FEAT.

Regardless of which party or president is responsible for introducing FOIA sensitive review at the EPA or any other agency, the practice still raises serious concerns. Although alerting or involving political appointees in FOIA administration does not violate the law per se—and may, in rare cases be appropriate—there is never any assurance that the practice will not lead to severe delays of months and even years. At its worst, sensitive FOIA review leads to intentionally inadequate searches, politicized document review, improper record redaction, and incomplete disclosure. When politically sensitive or potentially embarrassing records are at issue, politicians and bureaucrats will always have an incentive to err on the side of secrecy and non-disclosure.

Considering these developments, CoA Institute has submitted a FOIA request to the EPA seeking further information about FEAT and the agency’s sensitive review policy. We will continue to report on the matter as information becomes available.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.

EPA Chief of Staff describes agency’s sensitive review process for “politically charged” FOIA requests

Democrats on the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee (“OGR”) revealed new details last week about the processing of politically sensitive Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) requests at the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”). According to The Hill, Ryan Jackson, Chief of Staff to former Administrator Scott Pruitt and current Acting Administrator Andrew Wheeler, explained to “congressional investigators” how “‘politically charged’ or ‘complex’ requests . . . get an extra layer of review before being fulfilled, likely delaying” production of requested records. Jackson specifically discussed how the EPA determined that one Sierra Club FOIA request—described as a “fishing expedition”—was improperly broad. Other requests were delayed so that the disclosure of responsive records could “coincide with similar releases.” This politicization also benefitted requesters sympathetic to the Administration; one request from the National Pork Producers Council was “expedited” due to Jackson’s intervention when he set up a meeting with EPA policy officials.

Reports about FOIA politicization at the EPA are not new. At the beginning of May 2018, Politico reported that “top aides” had leaked internal emails showing the role of officials within the Office of the Administrator in reviewing “documents collected for most or all FOIA requests regarding [Pruitt’s] activities[.]” The apparent aim of this “sensitive review” was to limit the release of embarrassing or politically damaging records. House Democrats at OGR stepped into the game in early June 2018, demanding various records concerning the EPA’s policies for implementing the FOIA. To date, the agency has pointed only to publicly available records, thus prompting Ranking Member Elijah Cummings to ask Chairman Trey Gowdy to exercise his subpoena authority and compel a substantive response. (Incidentally, the EPA has previously ignored congressional records requests about FOIA politicization, as we explained in May 2014.)

The entire transparency community should be concerned over the heightening of sensitive review at the EPA. But it also is important to keep politics from clouding our understanding and criticism of the practice. As I wrote in May 2018:

It is true that the Trump Administration has enhanced sensitive review processes at the EPA. Other agencies have witnessed a similar expansion of sensitive review, as Cause of Action Institute’s investigation of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration demonstrates. But it would be a mistake—as I argued last December—to think that the Obama White House was any better at avoiding FOIA politicization. The EPA has a long and terrible track record for anti-transparency behavior. Consider the agency’s blatant weaponization of fee waivers. According to data compiled by the Competitive Enterprise Institute, and reported by Reason and The Washington Examiner, the Obama EPA regularly denied public interest fee waivers to organizations critical of the agency’s regulatory activities and the White House’s policy agenda. By contrast, left-leaning groups nearly always (92% of the time) received fee waivers.

Sensitive review, along with other forms of FOIA politicization, such as “White House equities” review, is a cherished tradition for both the Left and the Right. Regardless of which party controls the Executive Branch, the natural tendency will always be to keep embarrassing or politically sensitive records out of the hands of the public and—most especially—the news media. Cause of Action Institute itself was regularly subject to “sensitive review” during President Obama’s tenure, and we continue to be singled out for “special” treatment under President Trump, as records from the Federal Aviation Administration have shown. Regardless, we remain committed to exposing the practice of sensitive review and advocating for reform to combat all FOIA politicization.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.

Politics Clouding Criticism of the EPA’s Heightened Sensitive Review FOIA Procedures

Last week, a report from Politico revealed that the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) maintains a burdensome “sensitive review” process for Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) requests concerning Administrator Scott Pruitt’s activities. According to internal sources, officials within the Office of the Administrator have “reviewed documents collected for most or all FOIA requests regarding [Pruitt’s] activities[.]” The Politico report further claims that this “high-level vetting” has increased, as compared with the policies and practices introduced during the Obama years. “This does look like the most burdensome review process that I’ve seen documented,” argued Nate Jones from National Security Archive.

It is true that the Trump Administration has enhanced sensitive review processes at the EPA. Other agencies have witnessed a similar expansion of sensitive review, as Cause of Action Institute’s investigation of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration demonstrates. But it would be a mistake—as I argued last December—to think that the Obama White House was any better at avoiding FOIA politicization. The EPA has a long and terrible track record for anti-transparency behavior. Consider the agency’s blatant weaponization of fee waivers. According to data compiled by the Competitive Enterprise Institute, and reported by Reason and The Washington Examiner, the Obama EPA regularly denied public interest fee waivers to organizations critical of the agency’s regulatory activities and the White House’s policy agenda. By contrast, left-leaning groups nearly always (92% of the time) received fee waivers.

In addition to this viewpoint discrimination, the EPA suffered other transparency scandals. Former Administrator Lisa Jackson infamously used a fictional alter ego—“Richard Windsor”—to conduct agency business on an undisclosed government email account. And the EPA “misplaced” over 5,000 text messages sent or received by former Administrator Gina McCarthy and other top officials. The Obama-era EPA also tolerated the widespread use of personal email accounts by high-ranking bureaucrats, a practice that significantly frustrated public access to agency records and proved to foreshadow or parallel other FOIA scandals at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, the Department of Defense, and Department of Homeland Security, the Internal Revenue Service, and, most famously, the State Department. It is noteworthy that, in March of 2015, The Guardian—hardly a right-leaning paper—could seriously ponder: “Is the EPA having a transparency crisis?”

The history speaks for itself: the EPA under Scott Pruitt is not a new or unique threat to transparent government. The litany of FOIA abuses at the EPA and other agencies under both Presidents Obama and Trump demonstrate that we should fight the tendency to view the problem of FOIA politicization through a partisan lens. “Sensitive review” matured as a practice in the Obama Administration, and is continuing under President Trump, but there are institutional motivations for any and all bureaucrats, regardless of party affiliation, to frustrate the disclosure of records, particularly if they are embarrassing or raise the specter of media attention.

According to EPA Inspector General reports published in August 2015 and January 2011, the EPA’s FOIA regulations allow political appointees—including the Chief FOIA Officer and authorized disclosure official in the Office of the Administrator—to participate in approving requests and redacting records. Is it any wonder that an agency follows its own long-established rules for processing requests it deems “sensitive”? So long as the law gives the agency an opportunity to violate the spirit of the FOIA, the agency will take advantage of that discretion, even if it means violating statutory timelines for responding to requesters.

When Administrator Pruitt directed his staff to involve itself with the disclosure of records, he continued a tradition of obstructing the public’s right to access government information. He deserves the criticism he has received. But focusing on Administrator Pruitt’s (or President Trump’s) regulatory agenda, or his personal views on hot-button topics like global warming, obscures the underlying problem and makes it more difficult to reach consensus on how to address the real issues. The FOIA and implementing regulations, for one, need to prohibit “sensitive review,” or at least provide serious restrictions on its implementation. And guidance from the Department of Justice should address the troubling aspects that sensitive review can present. This should be part of a solution that everyone who believes in transparency can accept.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute