In passing the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) and the Federal Records Act, Congress intended for internal agency communications to be logged and, in many cases, retrievable under the FOIA. Attempts by agencies and officials to evade such transparency violate the core principles of government accountability and recently resulted in a highly publicized scandal that enveloped Secretary Hillary Clinton’s campaign for president.

So in the wake of the Clinton e-mail scandal, have agencies learned their lesson? For the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (“NOAA”), this doesn’t appear to be the case. Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) recently submitted multiple FOIA requests for NOAA’s records retention policies and internal communications from the time period surrounding the recent New England Fishery Management Council (“NEFMC”) meetings. In addition to asking for emails, CoA Institute also requested Google Chat/Google Hangout (“GChat”) records.

Anyone who regularly uses G-Mail is familiar with GChat and its “off the record” feature, which disables message logging. Unfortunately, a 2012 NOAA memo indicates that NOAA enabled the “off the record” feature agency-wide. There’s no indication that NOAA is using any other method to log these communications. This likely violates the Federal Records Act and frustrates public efforts to file FOIA requests seeking to better understand government decision-making.

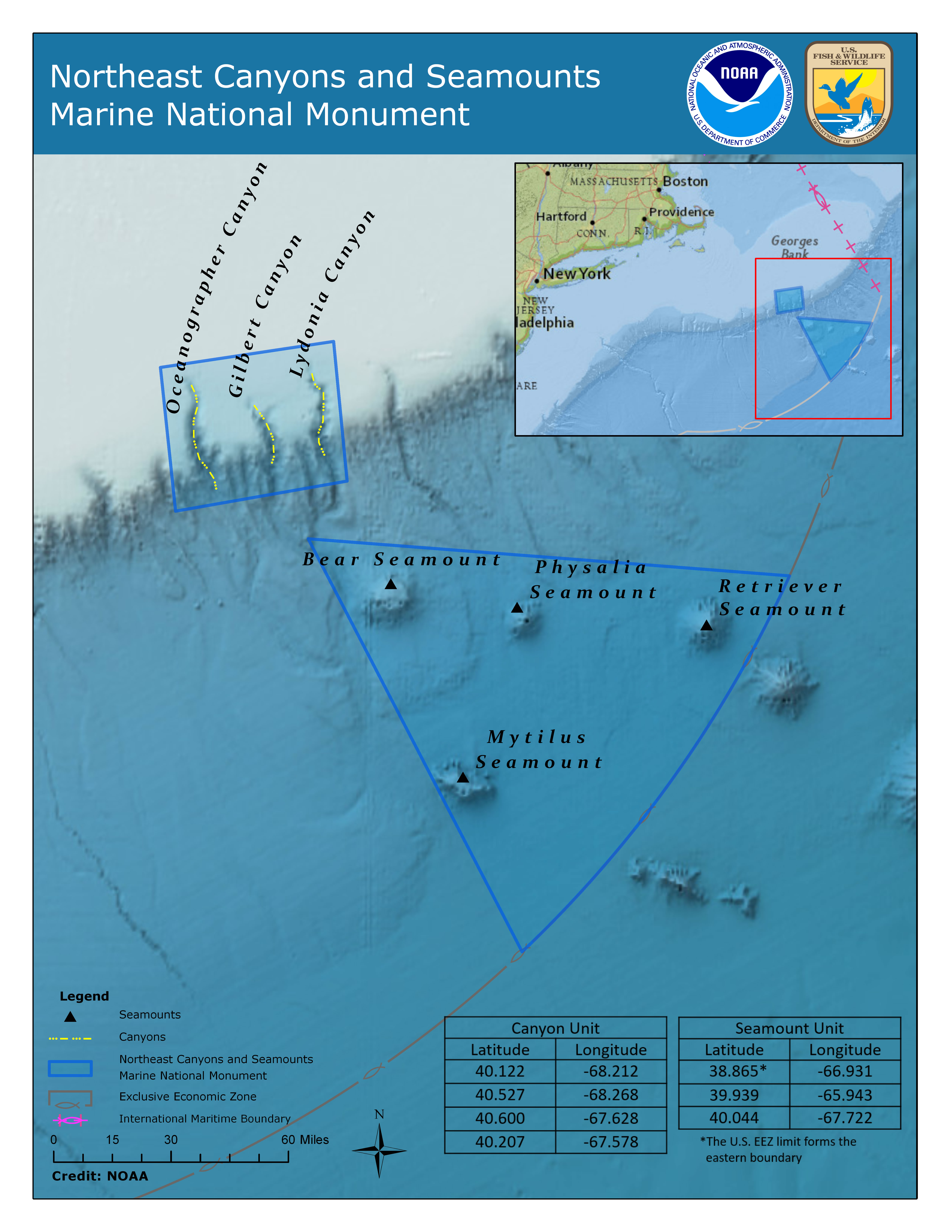

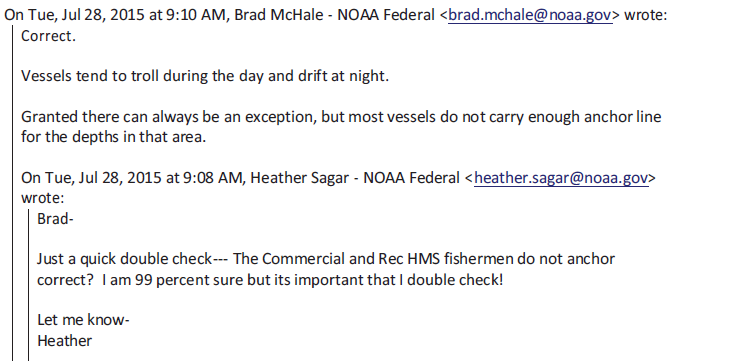

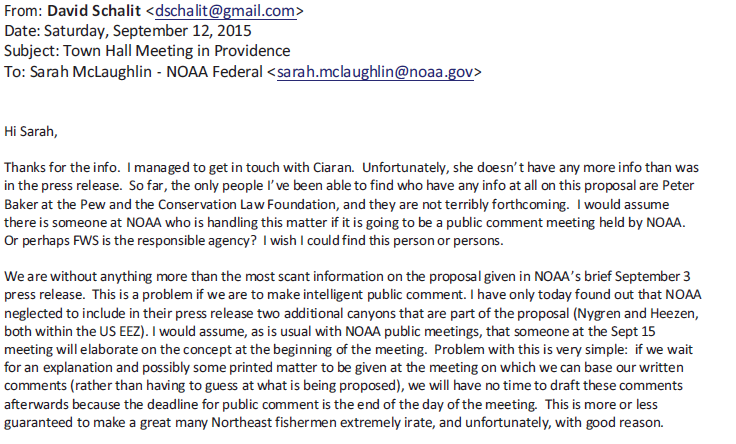

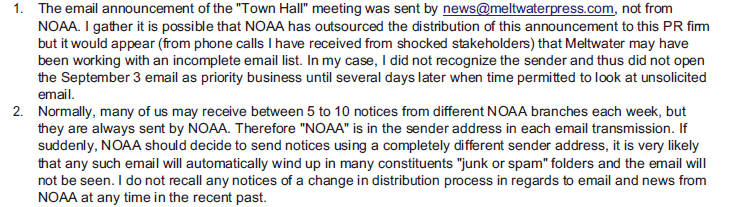

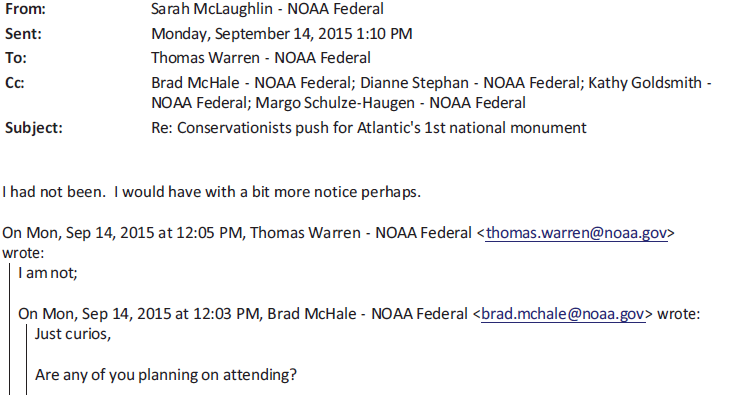

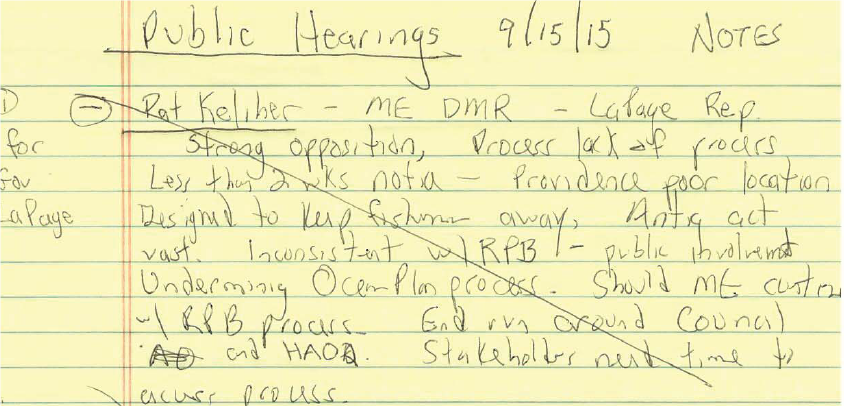

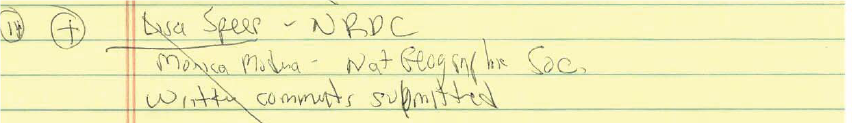

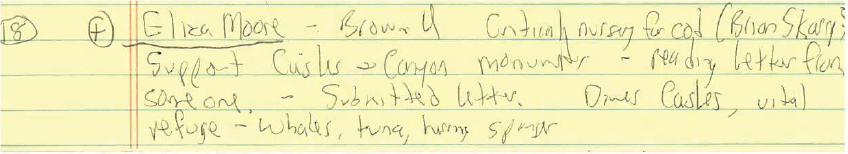

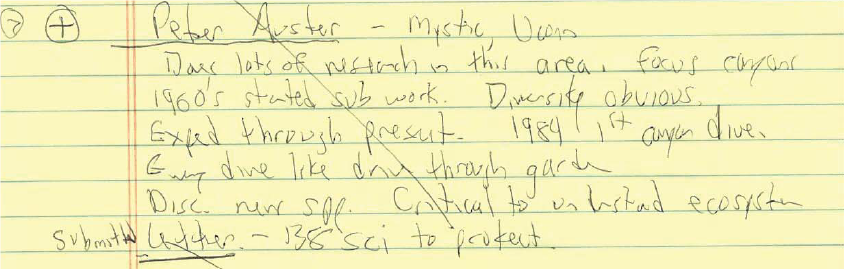

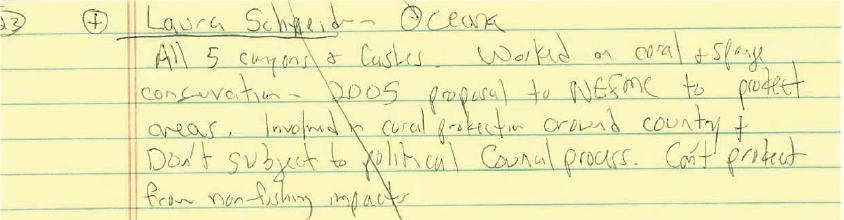

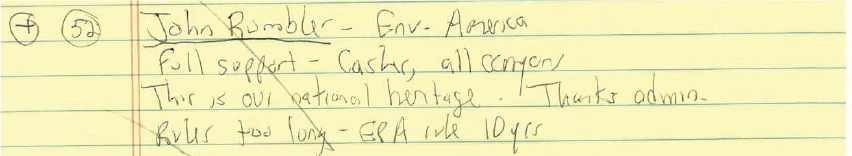

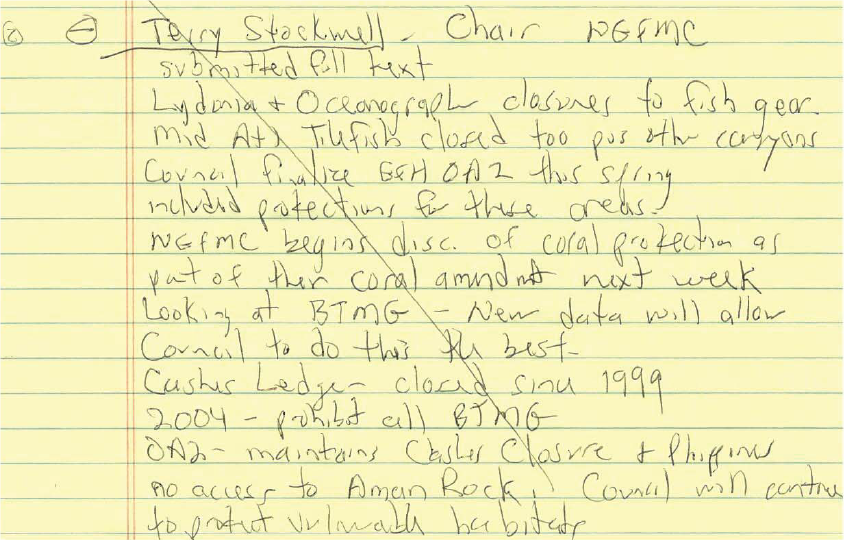

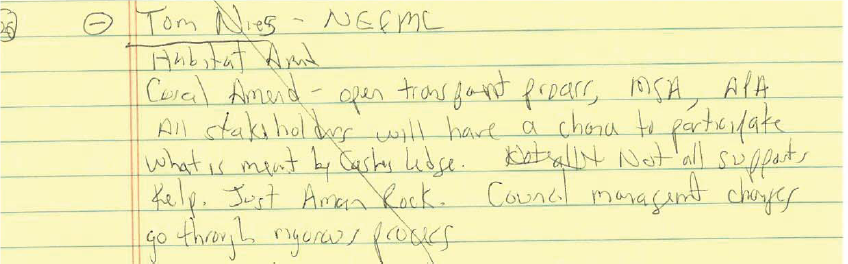

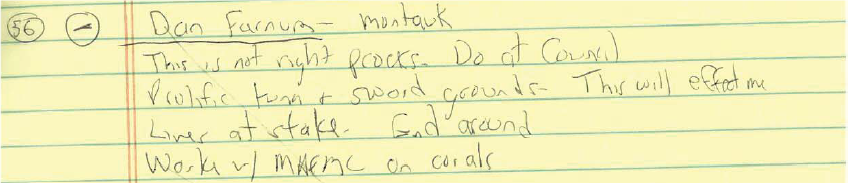

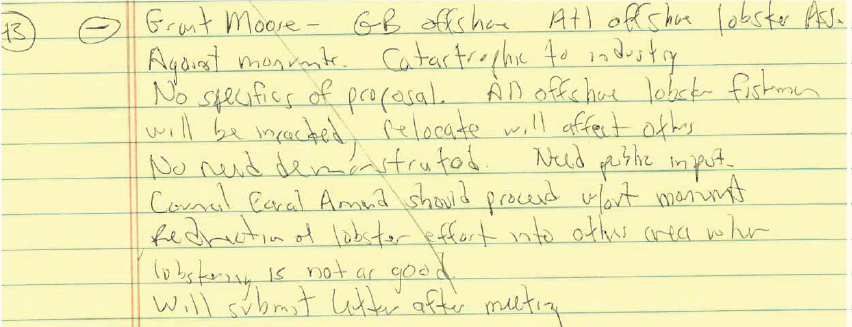

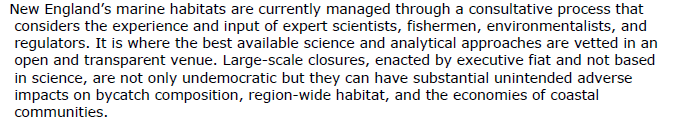

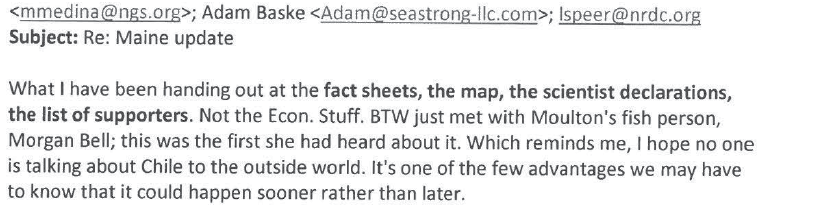

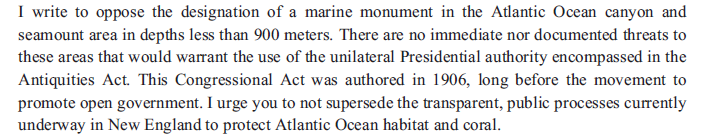

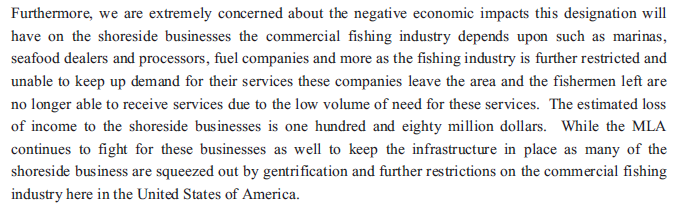

CoA Institute is interested in the communications between NOAA officials during the recent NEFMC meetings. These meetings were important because, at their conclusion, the NEFMC voted to adopt an amendment that would extend coverage of “at-sea monitors” on the fishing industry. This could have devastating effects on the ability of small-boat fishermen to continue to pursue their livelihoods. This amendment now goes to the Secretary of Commerce for his approval, and it is critical that the public understand the thought process used by NOAA to get this result, which would be revealed by reading its internal communications.

NOAA’s response to CoA Institute’s FOIA request was unusual. First, it declared the request was non-billable, meaning CoA Institute would not need to pay fees for compiling the information. This is appropriate given both the public interest in these records and CoA Institute’s status as a news media requester organization. NOAA later rescinded its non-billable determination and demanded CoA Institute submit more information relevant to the fee waiver request. CoA Institute did so, but, to date, NOAA has not responded. In our letter, we express concern with how NOAA is handling this request:

If NOAA is concerned that records responsive to this request will cast the agency in an unflattering light or reveal that its recordkeeping practices are in violation of law, it cannot weaponize fee waivers to prevent disclosure. To do so would not only be a violation of the law, but it would strike a grave blow to transparency.

With today’s lawsuit, NOAA has no choice but to produce the requested records. If the agency is unable to locate any GChat records because they were improperly deleted, NOAA must publicly admit this, immediately take steps to recover the records, and change its policies for future record retention to comply with the law.

Eric Bolinder is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.