- The ability to shroud government action in secrecy harms the rights of every American and undermines a free and open society

- Cause of Action Institute filed a FOIA request and later sued DOJ after former FBI Director James Comey admitted to using personal email to conduct official business

- Cause of Action Institute has been at the forefront of ensuring the government remains transparent and accountable as technology and communication channels have evolved

- DOJ provided the first installment of records relating to our lawsuit on Nov. 9, 2018, this blog relates to the latest installment of records and additional records are expected to be released at the end of December and January

Cause of Action Institute (CoA Institute) has obtained a second batch of former FBI Director James Comey and former FBI Chief of Staff James Rybicki’s emails sent or received on their personal, non-official email accounts to conduct agency business. The FBI’s latest records production is the second of four rolling productions. The FBI reviewed 518 pages of emails and released 439 pages to CoA Institute. Once again, these emails undermine Director Comey’s statements concerning the types of matters he discussed while using his personal email to conduct official business.

Last month, CoA Institute published the first set of records received as part of our FOIA lawsuit. Contrary to Director Comey’s representations to the DOJ that he never used his personal email account for “sensitive work,” the first batch of emails we obtained revealed otherwise. Those records included emails withheld in full and others redacted in part under the FOIA’s law enforcement exemption, which exempts from public disclosure certain sensitive information created or compiled for law enforcement purposes.

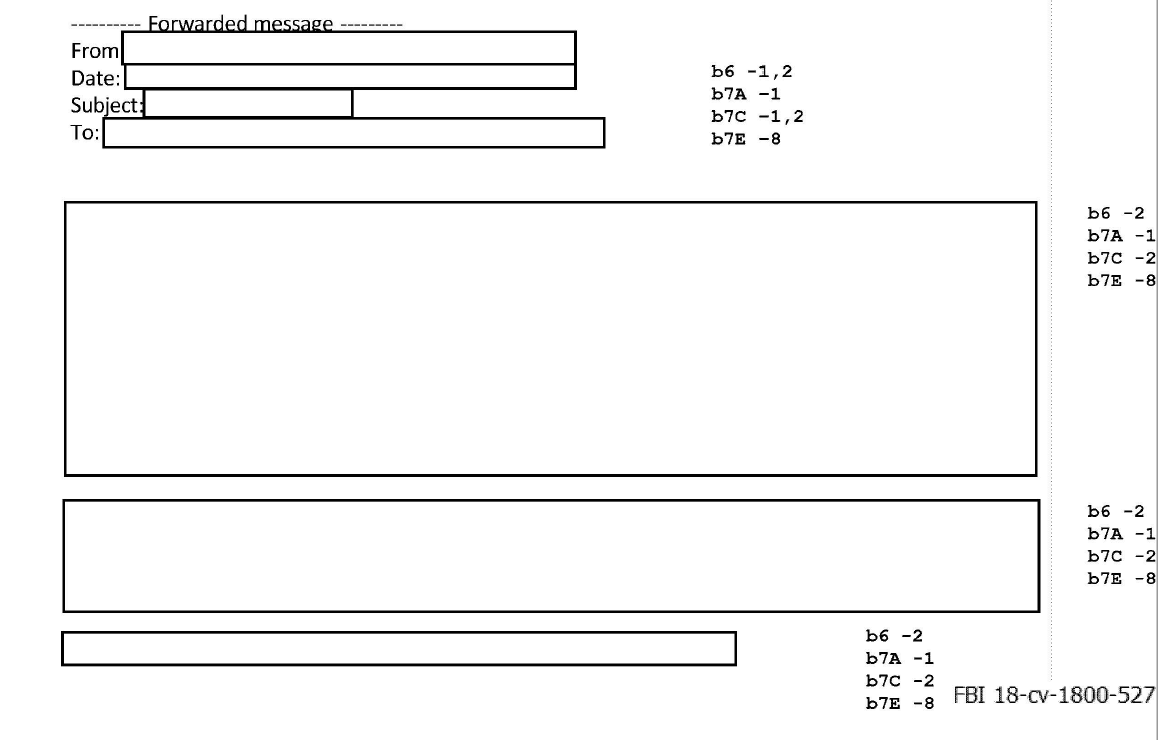

This new second batch of emails tells much of the same story. For example, the redactions in the completely redacted email below cite 3 bases for the application of the law enforcement exemption (b7A, C, & E). These exemptions pertain to information that, if released, could (A) interfere with law enforcement proceedings, (C) constitute an invasion of personal privacy, or (E) disclose law enforcement techniques and thereby risk circumvention of the law. In other words, the FBI determined that the work Director Comey conducted on his personal account was so sensitive in nature that it justified redaction under Exemption 7 of the FOIA to prevent disclosure to the public.

As explained in the FBI’s cover letter accompanying the production to CoA Institute, the FBI is only providing emails that Director Comey and his Chief of Staff forwarded or copied to their official FBI email accounts: “The FBI conducted email searches for any communications to or from James Rybicki’s and James Comey’s personal email accounts, located within Rybicki’s and Comey’s FBI email accounts.” This follows from Director Comey’s claims that all FBI-related work he conducted on Gmail was forwarded to an official FBI account. As Director Comey told the DOJ Inspector General:

“I was always making sure that the work got forwarded to the government account to either my own account or Rybicki, so I wasn’t worried from a record-keeping perspective was, because there will always be a copy of it in the FBI system.”

But if Director Comey misrepresented the nature of the work he conducted on his personal email account, a plausible concern arises as to whether Director Comey thoroughly searched and forwarded all work related emails from his personal account to his government account This is why using private email accounts for government business is so problematic: The agency—and ultimately the public—must rely on the very people who are violating the rules by using personal email accounts to forward their work-related emails to official government accounts. If they forget or choose not to copy an official account, there is little chance the agency will ever search for and recover the federal records created or received on those personal accounts. And that means those records cannot be produced to the public under the FOIA. The use of non-official accounts to conduct agency business, whatever the reasoning, imperils transparency, accountability, and good government, and it undermines trust.

You can view and download the documents here:

Part 1 (411 pages)

Part 2 (30 pages)

Kevin Schmidt is Director of Investigations for Cause of Action Institute. You can follow him on Twitter @KevinSchmidt8

Thomas Kimbrell is an Investigative Analyst at Cause of Action Institute.

____________________________________________________________

Media Contact: Matt Frendewey, matt.frendewey@causeofaction.org | 202-699-2018