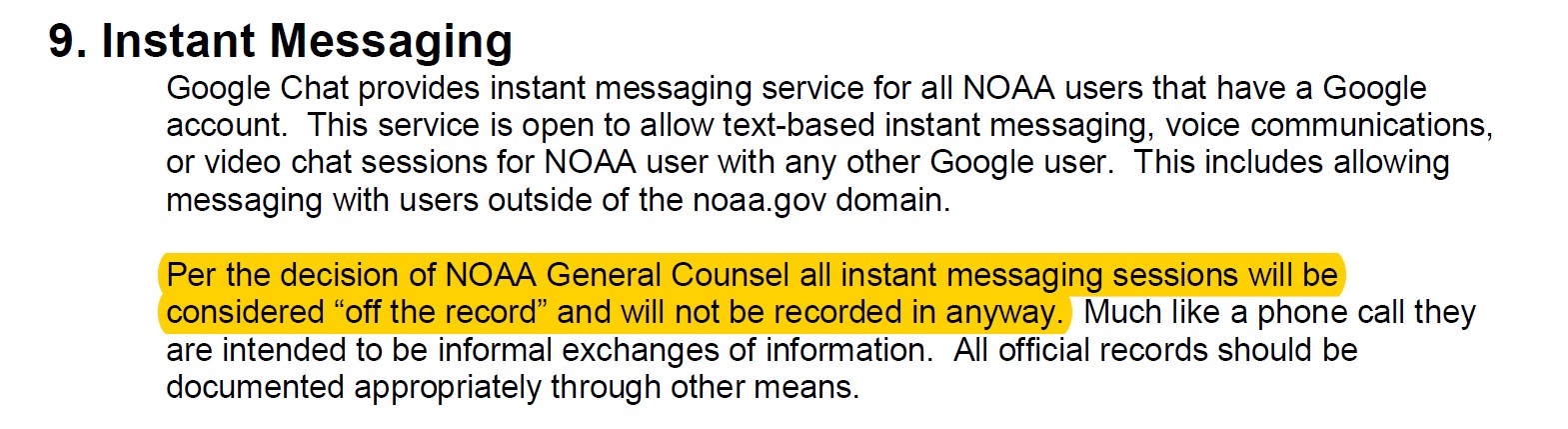

Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) filed a lawsuit last summer against the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (“NOAA”) seeking copies of electronic records created through the agency’s Google-based email platform. These types of records are commonly known as “instant messages.” The Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) requests at issue (available here and here) also sought formal agency guidance on the retention of “Google Chat” or “Google Hangouts” messages. We had already learned, through earlier investigation, that at least one internal NOAA handbook, dating from March 2012, instructed agency employees to treat all chat messages as “off the record,” raising concerns about potential unlawful record destruction at NOAA.

Media Coverage of CoA Institute’s Lawsuit Tipped-off the National Archives

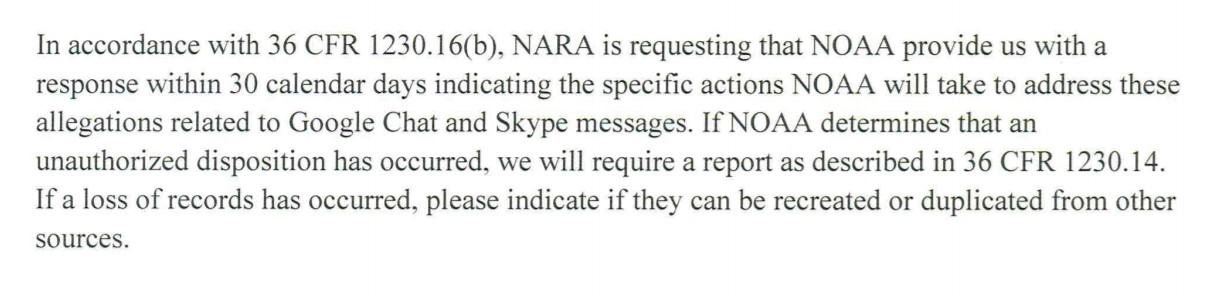

The Daily Caller News Foundation reported on CoA Institute’s lawsuit shortly after it was filed. Officials at the National Archives and Records Administration (“NARA”), which is tasked with policing federal records management across the government, took notice of the story and subsequently opened an inquiry on July 17, 2017 into CoA Institute’s allegations. NARA gave NOAA “30 calendar days” to indicate how it planned to address the retention of “Google Chat and Skype messages,” and, if necessary, to report an “unauthorized disposition,” that is, the improper destruction of records.

As far as we know, eight months later, NOAA still has not responded to NARA. We only learned about the NARA inquiry due to the agency’s recent decision to proactively disclose information on all pending investigations into the unauthorized disposition of federal records. We have filed FOIA requests with NOAA and NARA in order to discover the status of the inquiry, and we will provide further updates as more details become available.

The fact that CoA Institute had to file a FOIA request to obtain NOAA’s response to the NARA inquiry, as well as related communications, shows that NARA’s proactive disclosure regime on this topic could be improved. NARA should add another category of materials to its webpage that includes all correspondence received from an agency under investigation for the improper treatment of records.

NOAA’s Questionably Legal Google Chat Policy Flouts NARA Guidance

It goes without saying that an agency-wide policy to treat all chat messages as categorically “off the record” is problematic. Even if an agency expects its employees to keep business-related communications, which could qualify for retention under the Federal Records Act (“FRA”), off a chat-based platform, it is reasonable to assume that some messages worthy of preservation will be sent or received over instant messaging. NARA Bulletin 2015-02 makes that point clear. And even if some instant messages were not worthy of long-term historical preservation, they would still qualify as transitory records subject to NARA-approved disposition schedules.

A categorical policy such as the one that NOAA has adopted creates a moral hazard. Officials who want to thwart transparency can communicate with chat or instant messaging and, at least in this case, there is no way for the agency, NARA, or the public to catch them in the act. NOAA officials have been observed using Google Chat to communicate during a contentious meeting of the New England Fishery Management Council. If an agency like NOAA refuses to police how its employees are using the chat function on their Google-based email accounts, it should disable the function all together.

Regardless of whether electronic messages created through Google Chat or Google Hangouts are subject to the FRA, they may still be subject to the FOIA, which defines an “agency record” in broader terms than the FRA’s definition of a “federal record.” By failing to implement any sort of mechanism for preserving chat messages—even for the briefest period—NOAA is depriving the American public of access to records that could be particularly important in showing how the agency operates and regulates.

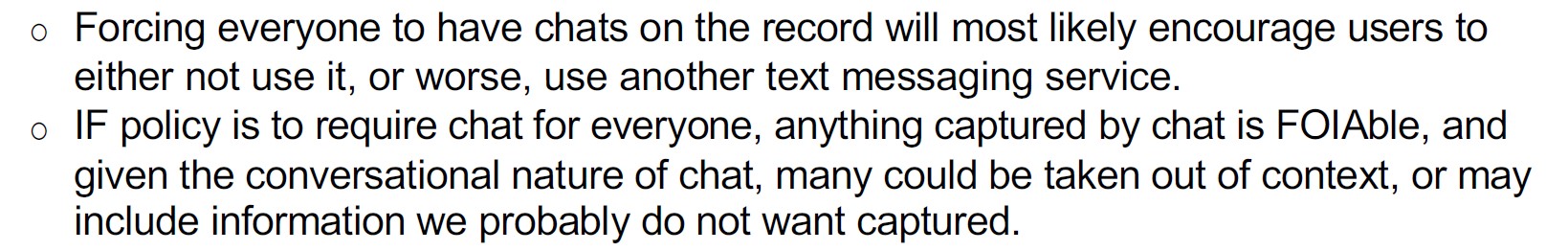

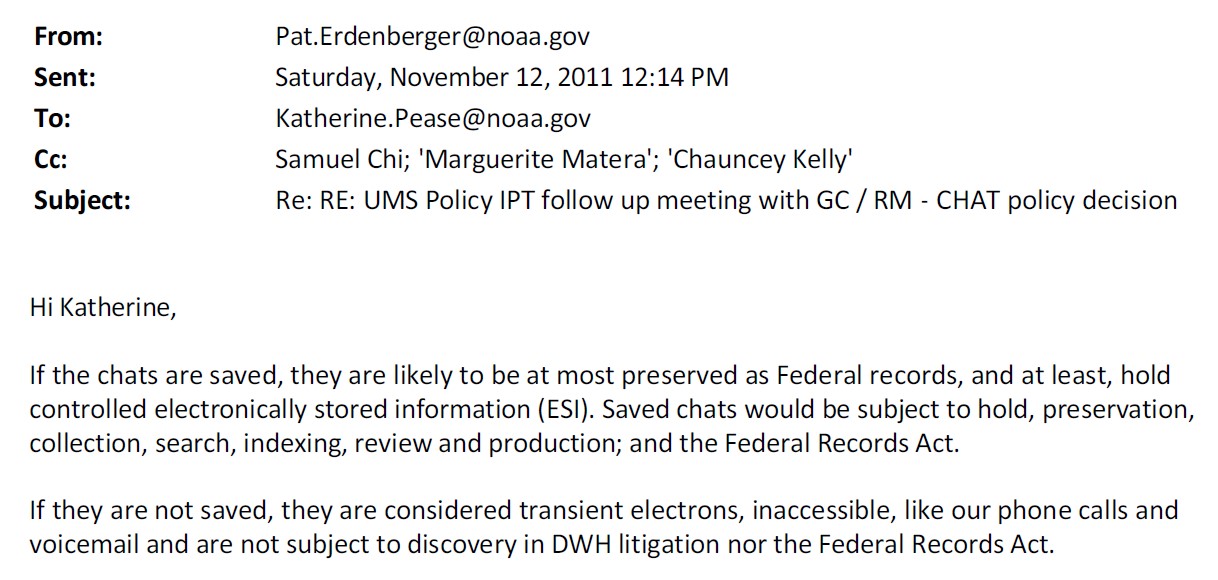

The worst part of this saga is that NOAA knew it was treading a thin line in deciding to treat Google Chat messages as “off the record.” According on documents obtained through the FOIA, NOAA’s lawyers and records management specialists were aware that electronic messages would need to be saved for public disclosure if Google Chat were “on the record.” Notes from an October 20, 2011 meeting reflect this:

NOAA also recognized that chat messages could, in theory, be subject to the FRA. Yet NOAA Records Officer Patricia Erdenberger reasoned that, by treating Google Chat as “off the record,” the agency’s FRA obligations could be bypassed. Making a questionable analogy to phone calls, Erdenberger suggested that chat messages be “considered transient electrons.”

Agencies must do a better job at keeping pace with evolving forms of technology. As one of my colleagues has argued, the use of non-email methods of electronic communication—including text and instant messaging, as well as encrypted phone applications like Signal—has serious implications for federal records management. The Department of Commerce, NOAA’s parent agency, has not updated it policy for handling electronic records since May of 1987. NARA, for its part, has been critical of the Department’s failure to revise this guidance, which is “heavily oriented towards the management of digital records on storage media such as diskettes and magnetic tape.” Still, thirty years is a long time for such inaction, even for the federal government. The transparency community must therefore intensify its efforts to hold the government accountable until more effective ways of handling electronic records are introduced.

Ryan Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute