Washington, D.C. (July 18, 2019) – U.S. District Court Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson yesterday denied the Internal Revenue Service’s (“IRS”) motion to dismiss Cause of Action Institute’s (“CoA Institute”) Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) lawsuit over the agency’s refusal to produce records relating to its dealings with Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation (“JCT”). To date, the IRS has refused to search for records potentially responsive to CoA Institute’s FOIA requests. The agency instead has argued that all relevant records would categorically be “congressional records” outside the scope of disclosure permitted under the FOIA. In its failed motion, the IRS claimed that the federal district court even lacked the authority—or subject-matter jurisdiction—to adjudicate CoA Institute’s well-pleaded claims in the first instance.

Newly Released Records Confirm IRS, DOJ Violated Taxpayer Confidentiality Law

Whether we like it or not, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) plays a central role in the administration of our tax laws. The agency consequently possesses copious amounts of sensitive financial information about individual Americans, nonprofits, and other corporations. Congress considered the protection of such information so important that it has mandated its confidentiality. Section 6103 of the Internal Revenue Code requires that “returns and return information”—essentially, anything about a taxpayer in IRS files—“shall remain confidential.” The importance of taxpayer confidentiality, and the danger inherent in its unauthorized disclosure, is one reason why the 2010 “Tea Party” targeting scandal was so serious—the Obama White House weaponized the IRS to target individuals and nonprofit groups based on their perceived political alignment.

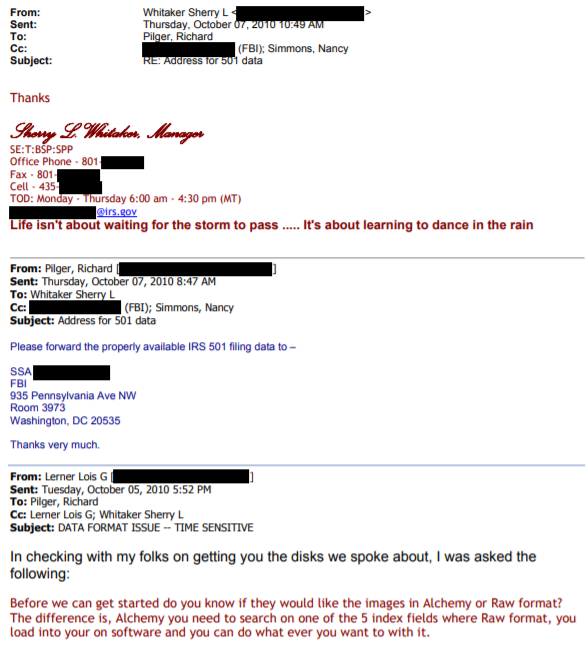

IRS records recently produced to Cause of Action Institute (CoA Institute) in a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuit now shed further light on how carelessly the IRS and the Department of Justice (DOJ) handled sensitive taxpayer information and only belatedly admitted to Congress that they had violated taxpayer confidentiality. In 2012, CoA Institute began its in-depth investigation into the nature and causes of the IRS targeting scandal and the misdeeds of government bureaucrats such as Lois Lerner. Part of our investigation revealed that IRS officials, including Ms. Lerner, willingly handed over twenty-one computer disks, containing over 1.1 million pages of taxpayer information, to the DOJ Public Integrity Section and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), despite lacking proper legal authorization to do so. This allegedly was done as part of the previous Administration’s efforts to investigate exempt entities suspected of having engaged in prohibited political activity.

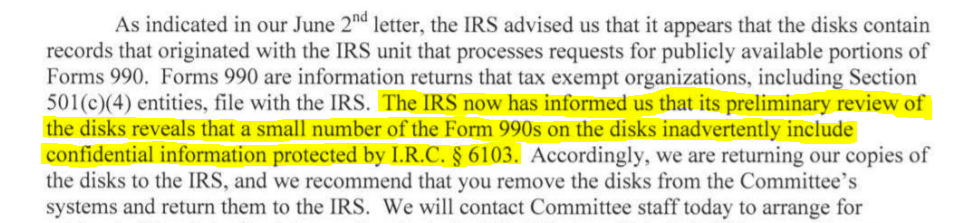

After repeatedly insisting that it had received only “publicly available portions” of Form 990s when the IRS turned over those 1.1 million pages of taxpayer information, the DOJ later admitted it was mistaken. The records received by CoA Institute confirm that was the case.

In two requests for investigation (here and here), CoA Institute explained why the IRS’s unauthorized disclosure constituted a serious breach of taxpayer confidentiality laws. But the DOJ Inspector General, while admitting that taxpayer data had been mishandled, choose to do nothing and merely stated that Congress had been “informed” and “this matter does not warrant further investigation.” The DOJ watchdog’s inaction led to a series of further FOIA requests (here, here, and here) that were designed to discover more about what the IRS and DOJ had done, and how Congress was alerted to the violation of Section 6103. CoA Institute obtained the requested records only after filing a lawsuit to compel disclosure.

Section 6103 sets out clear rules for the handling of tax information. Those rules are in place to protect taxpayer privacy. In this case, however, the rules were not followed. The DOJ never had proper authorization to obtain the nonprofits’ tax information, including information about donors. But the IRS nevertheless transferred 1.1 million pages of returns to the DOJ and agreed to provide the data in “raw” format, so that it would be easier for the FBI to process.

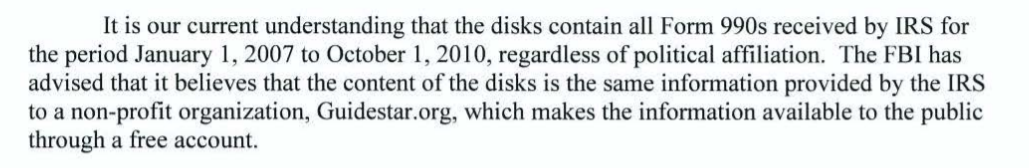

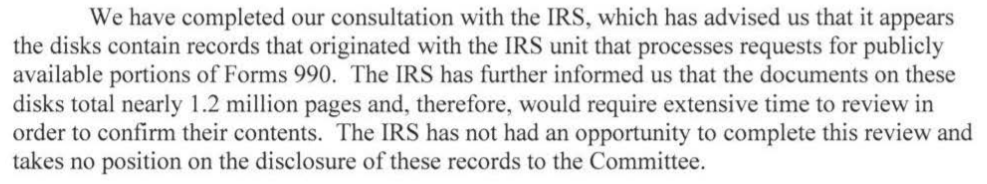

On May 29, 2014, after the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform opened an investigation into the unauthorized transfer of these tax returns, the DOJ claimed that it had obtained only publicly available information, such as the returns available online on Guidestar.org.

Days later, on June 2, 2014, the DOJ again argued that the trove of tax information it obtained from the IRS was not confidential.

And then, only two days after that, the DOJ changed its story—the agency admitted that the IRS had discovered confidential Section 6103 information within the 1.1 million pages of returns and return information. The DOJ claimed that the disclosure had been “inadvertent,” and it indicated that it was “returning [its] copies of the disks to the IRS[.]” Unfortunately, it is impossible to judge just how serious this “inadvertent” breach of confidentiality was because the DOJ has refused to furnish the House Oversight Committee with internal correspondence about the incident. It has withheld this correspondence by citing the deliberative process privilege—a species of executive privilege— and, to date, those records remain secret.

To be clear, by returning the twenty-one CDs to the IRS and informing Congress about what happened, the DOJ followed proper procedure. But that does not exonerate the federal government for having allowed the breach of taxpayer confidentiality to have happened in the first place. All citizens deserve to know their government does not act with political motivations, and that the IRS will safeguard sensitive taxpayer information, especially as it pertains to charitable giving and the operation of nonprofit entities.

The DOJ’s delayed disclosure of records, which finally give a complete picture of what happened, also illustrates another danger of politicization, namely, of the FOIA process. In this case, the DOJ put up so many hurdles to accessing these records that it required a lawsuit to compel disclosure. Even then, it took months for the agency to produce the records. It would have been next to impossible for an ordinary citizen to get the same result.

For government to be truly transparent, it must be held accountable by its citizens. The behavior of the IRS and DOJ in this case is a perfect illustration of why CoA Institute is committed to fighting for an open and transparent government. Government agencies should not be allowed to violate statutes and then stonewall requests that seek to expose the truth. That is why we pursued this investigation and why we will continue to vigorously serve as a government watchdog on behalf of every American.

Ryan Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.

IRS Gives Nod to Its Regulatory Noncompliance, Doesn’t Address Real Issues

The Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) is notorious for flouting regulatory procedures that are designed both to legitimize the administrative state’s exercise of lawmaking power and to constrain the worst abuses of that authority through information gathering tools and judicial review. One reason the IRS is able to avoid the traditional regulatory process is because the Anti-Injunction Act prevents most lawsuits that would invalidate rules that the IRS promulgates outside that process.

Last week, the IRS acknowledged some of those shortcomings in a policy statement announcing changes to the way it rolls out new rules. These changes are on top of last year’s revocation of a decades-old exemption from White House pre-publication review and approval.

The Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) has different processes for legislative and interpretative rules, i.e., rules that create new legal obligations on private parties and those that purportedly don’t. The IRS has long maintained that nearly all its rules are interpretative and thus exempt from the APA and notice-and-comment regime. This is a dubious claim, at best. Notwithstanding this self-bestowed exemption, the IRS magnanimously still puts its supposedly interpretative rules out for notice and comment. But it does so without following all of the required procedures, which it justifies by claiming that any process it is following is voluntary anyway, so it can follow which procedures it wants to. In its policy statement, the IRS confirmed that it “will continue to adhere to [its] longstanding practice of using the notice-and-comment process for interpretive tax rules.”

IRS Won’t Seek Deference

An issue that has plagued the IRS is the use of subregulatory guidance to explain the IRS’s view on how it will apply statutes and regulations; these guidance documents often come in the form of revenue rulings, revenue procedures, notices, and announcements. Although these documents are supposed to be interpretative and explanatory, in many cases they create new legal obligations and are thus actually legislative in nature.

For example, the IRS used a subregulatory mechanism to announce new “transactions of interest” that captive insurance companies must report to the IRS or face a penalty and enforcement. This is a classic case of a new law that affects private parties that was slipped through in a policy document, without notice and comment, and which should be invalidated on those grounds.

The IRS now seems to be conceding the issue broadly, although not with regard to the example above, and announced in its policy statement that:

When proper limits are observed, subregulatory guidance can provide taxpayers the certainty required to make informed decisions about their tax obligations. Such guidance cannot and should not, however, be used to modify existing legislative rules or create new legislative rules. The Treasury Department and the IRS will adhere to these limits and will not argue that subregulatory guidance has the force and effect of law. In litigation before the U.S. Tax Court, as a matter of policy, the IRS will not seek judicial deference under Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452 (1997) or Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984), to interpretations set forth only in subregulatory guidance.

This is a positive development, but it remains to be seen whether IRS attorneys really will abide by the constraint when faced with a rule that they’re trying to save in court. Further, the policy only applies in “litigation before the U.S. Tax Court,” and so will not apply when challenges are brought to federal district court, as many procedural challenges to rulemaking are. Another limitation of the statement appears to be that the IRS is only forswearing seeking deference to interpretations of subregulatory tax guidance and not other rules that litigants might dispute the IRS has violated, such as the APA or the Regulatory Flexibility Act, which the IRS claims does not apply to nearly all of its rules.

“Good Cause”

One of the APA procedures the IRS sidesteps is providing “good cause” for when interim final rules become immediately effective upon publication. Treasury and the IRS have decided to now “commit to include a statement of good cause when issuing any future temporary regulations under the Internal Revenue Code.” This is a good, if minor, change and adherence to general practice used elsewhere in the government.

The biggest issue plaguing the IRS’s compliance with procedural rules that constrain the agency is the Anti-Injunction Act, which prevents many challenges that would clean up the IRS’s lack of compliance. Unless and until there is a shift in judicial interpretation of that provision or Congress exempts Title 5 challenges to IRS rules, we will continue to see the IRS operate outside the bounds of standard administrative practice. The IRS’s recent policy statement does nothing to change that.

James Valvo is counsel and senior policy advisor at Cause of Action Institute.

Cause of Action files lawsuit against DOJ relating to Lois Lerner-IRS data scandal

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Sept. 14, 2018 – Cause of Action Institute (CoA Institute) has filed a lawsuit against the Department of Justice (DOJ) seeking records relating to the infamous Lois Lerner-IRS scandal. In 2010, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) improperly released 21 CDs of confidential taxpayer information to the DOJ. This illegal release of confidential tax information resulted in several internal investigations, but the government has refused to release any of its internal reports or communications relating to the scandal.

“Taxpayers deserve to a have a full and clear picture of what took place nearly a decade ago when the U.S. Department of Justice and Internal Revenue Service were partnering in an effort to target nonprofits,” said Ryan Mulvey, counsel at Cause of Action Institute. “We have repeatedly requested the release of the internal investigation reports and the records revealing when and what the DOJ shared with Congress about this improper release. Taxpayers deserve a clear picture of who knew what and what really took place in the targeting of nonprofits by the DOJ and the IRS.”

In its investigation of this matter, CoA Institute has engaged with various DOJ components and Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA), filed multiple unanswered Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, and sought records regarding the potentially illegal access to and disclosure of this confidential taxpayer information.

Background:

- In 2013, the public learned that the IRS Exempt Organizations Section, led by then-Director Lois Lerner, had been involved in unfairly targeting nonprofits, allegedly for political purposes.

- Before then, the IRS and DOJ met on several occasions to discuss targeted prosecutorial efforts.

- At one of those meetings, the IRS improperly provided the DOJ with 21 CDs containing statutorily protected confidential taxpayer information. That information could have been disclosed to the DOJ pursuant to statutory exemptions, none of which applied to this disclosure.

- DOJ returned to the IRS, the CDs contained 1.1 million pages of confidential information regarding tax return information of various tax-exempt groups.

- CoA Institute wrote to both the TIGTA and the DOJ Office of Inspector General (DOJ OIG) to request investigations into this illegal access to and disclosure of confidential taxpayer information. TIGTA and DOJ OIG both opened investigations of this matter.

- TIGTA refused to release its findings.

- DOJ OIG, in a letter to CoA Institute, explained that, “[b]ased upon [its] initial inquiries, it appears that some protected taxpayer information was included on compact disks (CDs) that the IRS provided to the Department in response to a Department request.” Once “the Department learned of this, it returned the CDs to the IRS and informed Congress about it.” Citing “the absence of available information,” DOJ-OIG “determined that [CoA Institute’s request] does not warrant further investigation.”

- In October 2016, CoA Institute sent a FOIA request to the DOJ-OIG seeking records of its communication with Congress relating to this unauthorized disclosure.

- In October 2017, CoA Institute sent two additional FOIA requests to various DOJ components to ensure that CoA Institute received all relevant records pertaining to the IRS’s unlawful disclosure, particularly regarding the DOJ’s communications with Congress.

- DOJ has refused to respond to any of the CoA Institute FOIA requests for this matter.

- On Thursday, Sept. 13, 2018 Cause of Action Institute filed the following complaint against the U.S. Department of Justice, Cause of Action Inst. v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, 18-2126 (D.D.C.)

Full complaint can be viewed below.

About Cause of Action Institute

Cause of Action Institute is a 501(c)(3) non-profit working to enhance individual and economic liberty by limiting the power of the administrative state to make decisions that are contrary to freedom and prosperity by advocating for a transparent and accountable government.

Media Contact:

Matt Frendewey

matt.frendewey@causeofaction.org

202-699-2018

Loading...

Loading...

Federal District Court Excuses IRS’s Refusal to Search for Email Records Concerning White House Interference with the FOIA

Last week, Judge Emmet Sullivan of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia issued an order denying Cause of Action Institute’s (“CoA Institute”) cross-motion for summary judgment in a Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) brought against the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”). The opinion was long awaited—summary judgment briefing ended over a year-and-an-half ago. Although we do not intend to appeal the decision, it is worth highlighting some issues with Judge Sullivan’s opinion and the IRS’s arguments. The case is a fine example of how courts too frequently defer to agencies when it comes to policing their compliance with the FOIA.

Background: “White House equities” review and FOIA politicization

In March 2014, CoA Institute published a report revealing the existence of a non-public memorandum from then-White House Counsel Gregory Craig that directed department and agency general counsels to send to the White House for consultation all records involving “White House equities” when collected in response to any sort of document request. This secret memo stands in stark contrast to President Obama’s January 2009 directive on transparency, as well as Attorney General Holder’s March 2009 FOIA memo. Although originally praised as setting the bar for open government, the Washington Post eventually described the Obama Administration as one of the most secretive governments in American history.

As part of the system of politicized FOIA review established under the “White House equities” policy, whenever a requester sought access to records deemed politically sensitive, potentially embarrassing, or otherwise newsworthy, the agency processing the request would forward copies of those records to a White House attorney for pre-production review. Not only did the entire process represent an abdication of agency responsibility for the administration of the FOIA, but it severely delayed agency compliance with the FOIA’s deadlines. As we have previously suggested, “White House equities” review likely continues under the Trump Administration.

The specific FOIA request at issue in this case, which was submitted to the IRS in May 2013, sought records of communications between IRS officials and the White House reflecting “White House equities” consultations. Similar requests were sent to eleven other agencies. All those agencies produced the requested records; only the IRS failed to locate a single relevant document. And the IRS only communicated its failure to find any responsive records two years after CoA Institute submitted its request and filed a lawsuit.

Why the IRS failed to conduct an adequate search for records

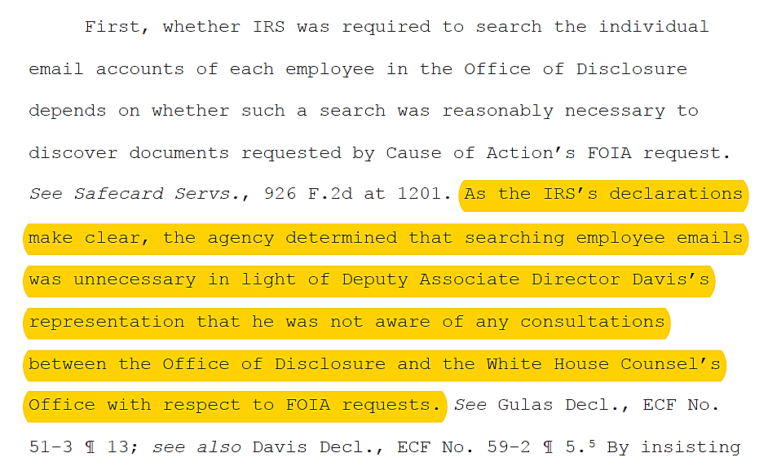

Our argument for the inadequacy of the IRS’s search for records reflecting “White House equities” consultations focused on several points, but two were especially important. First, the IRS failed to search its own FOIA office—the most likely custodian of the records and issue. Second, the IRS improperly refused to search for any responsive email correspondence within the Office of Disclosure.

The IRS inexplicably limited its search efforts to the Office of Legislative Affairs, a sub-component of the Office of Chief Counsel, and the Executive Secretariat Correspondence Office, which handles communications with the IRS Commissioner. The agency offered no evidence that it sent search memoranda to its FOIA office, which is part of the “Privacy, Governmental Liaison, and Disclosure” or “PGLD.” In fact, the IRS effectively admitted that it had foregone a search of the Office of Disclosure because a single senior employee testified that he did not believe any responsive records existed. And because “White House equities” review was not mentioned in the Internal Revenue Manual, the FOIA officer assigned to CoA Institute’s request determined that consultations with the White House would never have taken place.

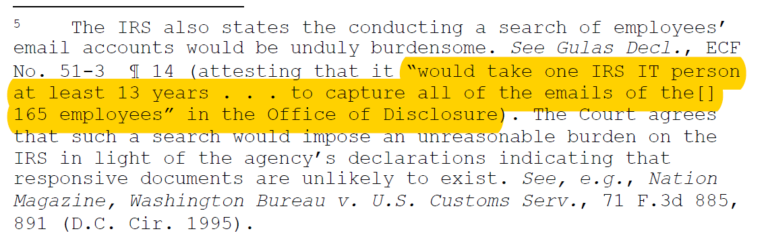

The IRS also refused to search individual email accounts within the Office of Disclosure because it would be too “burdensome.” Remarkably, the IRS claimed it would “take one IRS IT person at least 13 years” to capture the correspondence of all 165 employees within the Office of Disclosure. Yet the IRS offered no explanation for why other reasonable options to search email did not exist, such as requiring individual employees to “self-search” email, conducting a preliminary sample search of individuals within the Office of Disclosure most likely to have responsive records, or making use of e-discovery tools like “Clearwell” and “Encase.”

The Court’s Flawed Opinion and Hyper-Deference to the IRS

One major flaw in the Court’s decision concerns its uncritical acceptance of a single IRS attorney’s belief about the existence of responsive records within the Office of Disclosure. Although the IRS admittedly conducted a keyword search of its tracking system for incoming FOIA requests, it refused to send out search memoranda or engage in other typical search efforts. The IRS instead relied on the declaration of John Davis, Deputy Associate Director of Disclosure, who claimed that he had never heard of “White House equities” and was unaware of White House consultations ever taking place. On this basis alone, the IRS concluded it was “unreasonable” to conduct a more vigorous search. The Court accepted this reliance without any real explanation when it should have given more consideration to the text of the Craig Memo, which was addressed to the entire Executive Branch—including the IRS—and the fact that the eleven co-defendants in the same case all produced responsive records—nearly all of which were email chains.

As for the search of individual email accounts, the Court yet again uncritically deferred to the IRS’s bizarre claim that it would take thirteen years to process CoA Institute’s FOIA request.

In deferring to the IRS, the Court failed to address the IRS’s practice of conducting email searches by manually inspecting the content of individual hard drives, a central reason why an email search would take so preposterously long. This practice, which requires the IRS to warehouse a lot of old computer equipment, has been repeatedly criticized by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration because it could lead to violations of records management laws.

Additionally, some doubt exists, based on information independently received by CoA Institute from IRS employees, as to the accuracy of the IRS’s claims regarding its ability to conduct an agency- or component-wide search of its email system. Because FOIA cases rarely make it to trial, it is nearly impossible to pin the IRS down on the accuracy of its claims. Regardless, the IRS has certainly made a habit of regularly evading its disclosure obligations, a habit buttressed in this instance by an overly deferential judiciary.

Ryan Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute

CoA Institute Responds to Opinion in FOIA Case Against IRS

On Tuesday, June 12, the District Court for the District of Columbia issued an opinion in CoA Institute’s long-standing FOIA suit against the IRS for failing to produce records regarding possible White House intrusion in to the agency’s FOIA practices. The opinion can be found here.

A few thoughts on this opinion from the District Court for the District of Columbia in our #FOIA case against the @IRSnews. For background, here's what we asked for: comms between IRS & White House on doc requests https://t.co/odRkq3P7Au pic.twitter.com/bGDKQIm2VH

— Cause of Action Inst (@CauseofActionDC) June 12, 2018

The first clause of our #FOIA request states: “All records, including but not limited to emails.” Despite that fact, the court accepted the IRS’ decision not to search employee emails. pic.twitter.com/Qh7pYFy9Ge

— Cause of Action Inst (@CauseofActionDC) June 12, 2018

What’s worse, the court also accepted the IRS’ position that searching employee email is “unduly burdensome” because it would take an IT staffer 13 years to search. That’s nonsense. pic.twitter.com/qDvbeFd5Nz

— Cause of Action Inst (@CauseofActionDC) June 12, 2018

The #IRS takes the bizarre position that to search staff email accounts the IT department has to mirror their hard drives one by one, and then do a search for emails. That’s how they generate those huge search times. No other agency does this.

— Cause of Action Inst (@CauseofActionDC) June 12, 2018

As the court well knows, 11 other agencies provided documents when we sent this same #FOIA to them. Only the IRS was unable to comply.

— Cause of Action Inst (@CauseofActionDC) June 12, 2018

Summary:

CoA sends 12 FOIAs seeking comms re: White House involvement in #FOIA in 201311 Agencies: Here you go.@IRSnews: Unduly burdensome.

CoA: /sigh – Fine, we’ll sue.

Court: Nah, they’re good. Don’t worry about it.

Transparency denied after 5 years.

— Cause of Action Inst (@CauseofActionDC) June 12, 2018

Oversight Victory: Tax Regulations Now Subject to OMB Review

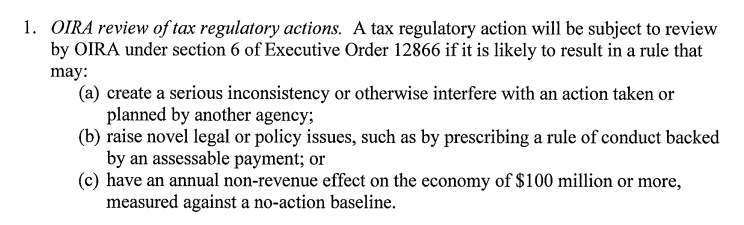

In a major win for oversight and constitutional governance, the White House Office of Management and Budget (“OMB”) and the Department of the Treasury have scrapped a decades-old agreement that exempted many IRS tax regulations from independent review and oversight. In its place, the agencies have set up a new agreement that requires Treasury to submit important tax regulations to OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (“OIRA”) for review pursuant to Executive Order 12,866 (“EO 12,866”) just like nearly every other agency.

This change came after an investigative report from Cause of Action Institute and a sustained campaign over the past few months from supporters of OIRA review. From a transparency perspective, this agreement is already an improvement because it has been announced publicly, posted on Treasury’s website, and not kept secret for thirty-five years, like the previous agreement.

The New Memorandum of Agreement

The new agreement will require Treasury to submit the following categories of tax regulations to OIRA for review:

All three categories are well conceived. First, one of the main focuses of OIRA review has always been interagency consultation. And IRS rules can overlap with rules from the Department of Labor and, increasingly in the wake of the Affordable Care Act, the Department of Health and Human Services. Allowing those and other agencies to weigh in on proposed tax regulations is an appropriate and necessary level of oversight, and can lead to better policymaking. At the Senate hearing where the agreement was unveiled, Senator Lankford asked Treasury General Counsel Brent McIntosh who will make the determination of whether a new rule is likely to create a conflict with another agency. McIntosh replied that, under the agreement, Treasury will submit a list of rules to OIRA on a quarterly basis and OIRA will then be in a position to flag rules that may create a conflict.

Second, Treasury will send OIRA tax regulations that raise novel legal or policy issues. These are exactly the type of rules should not be decided in a vacuum and when independent review from OIRA and others can provide a fresh look at novel questions. This is also an existing category of rules that are covered by EO 12,866 and so it makes sense to include tax regulations in this existing mandate.

Third, and finally, the new agreement includes tax regulations that are likely to have an annual non-revenue impact on the economy of $100 million or more. This is the existing threshold for significant regulatory actions for other agencies. The agreement makes a distinction for the “non-revenue” impact of tax regulations. This is a commonsense distinction because OIRA review and cost-benefit considerations should be focusing on the distortionary impacts of regulatory choices, not money transferred to the fisc. This modification of the existing language in EO 12,866 was necessary to fit the existing system to the way tax regulations work. At the hearing, Senator Lankford asked McIntosh which rules from the 2017 tax cuts may meet this threshold. McIntosh estimated that rules related to pass-through entities, interest expense deductions, bonus depreciation, section 199A, partnerships under section 512, and section 951A could now be subject to OIRA review.

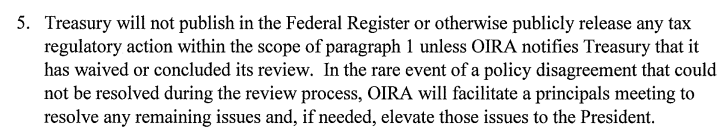

The New MOA Puts OIRA in Control

The new agreement includes an important provision that bars Treasury from rushing rules out the door to the Federal Register before OIRA has signed off.

In order for the president and the White House to properly oversee the Executive Branch, they must be able to control its regulatory actions. This provision makes it explicit that OIRA gets the final say.

Agreement Addresses Concerns about Delay and Expertise

Perhaps the biggest pushback against subjecting tax regulations to the same review that applies to other agencies’ rules was concerns about delay. The new agreement addresses that issue by putting a 45-day clock on OIRA review and a special 10-business-day expedited review for rules stemming from the 2017 tax cuts. Responding to concerns about OIRA’s expertise, Administrator Naomi Rao announced that Minnesota Law Professor and tax administration expert Kristin Hickman was joining OIRA as an advisor. And OMB has been staffing up on other tax experts as well.

Concerns about the New Agreement

There is at least one concern about the agreement. It only applies to “tax regulatory actions,” which the agreement gives the same meaning as “regulatory actions” in EO 12,866. That definition covers “any substantive action by an agency (normally published in the Federal Register) that promulgates or is expected to lead to the promulgation of a final rule or regulation, including notices of inquiry, advance notices of proposed rulemaking, and notices of proposed rulemaking.” Noticeably absent from this definition are interpretative rules that are not published in the Federal Register. The IRS is notorious for trying to claim that its rules are interpretative and do not need to follow the strictures of the Administrative Procedure Act. (CoA Institute recently filed an amicus brief in a case challenging this behavior.) It remains to be seen whether the IRS and Treasury will try to assert that interpretative rules do not meet the definition of a “regulatory action” under EO 12,866 and thus do not need to be sent to OIRA for review. A fair reading of the term “regulatory action” should include interpretative rules, even under the IRS’s improperly broad definition of that term.

But overall a dramatic improvement in the oversight of tax regulations and milestone in the project to end so-called tax exceptionalism and bring IRS under the same administrative law as everyone else.

James Valvo is Counsel and Senior Policy Advisor at Cause of Action Institute. He is the principal author of Evading Oversight. You can follow him on Twitter @JamesValvo.