Last month, Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) released an investigative report detailing a pernicious practice at the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”). The agency claims that none of the economic impact caused by its rules is attributable to its regulatory choices. Instead it says the impact flows from the underlying statute. The IRS uses this claim to evade three important oversight mechanisms. When we released the report, we called on Congress to press whomever President Trump nominated to be the next IRS commissioner to promise to reform this practice. Well, Trump just nominated Chuck Rettig to head the agency. So it’s time for Congress to stand up and hold the IRS accountable for its decades-long practice of playing by its own rules.

CoA Institute just sent a letter to Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch and Ranking Member Ron Wyden urging them to press Mr. Rettig on this issue during their face-to-face meetings and at a public hearing.

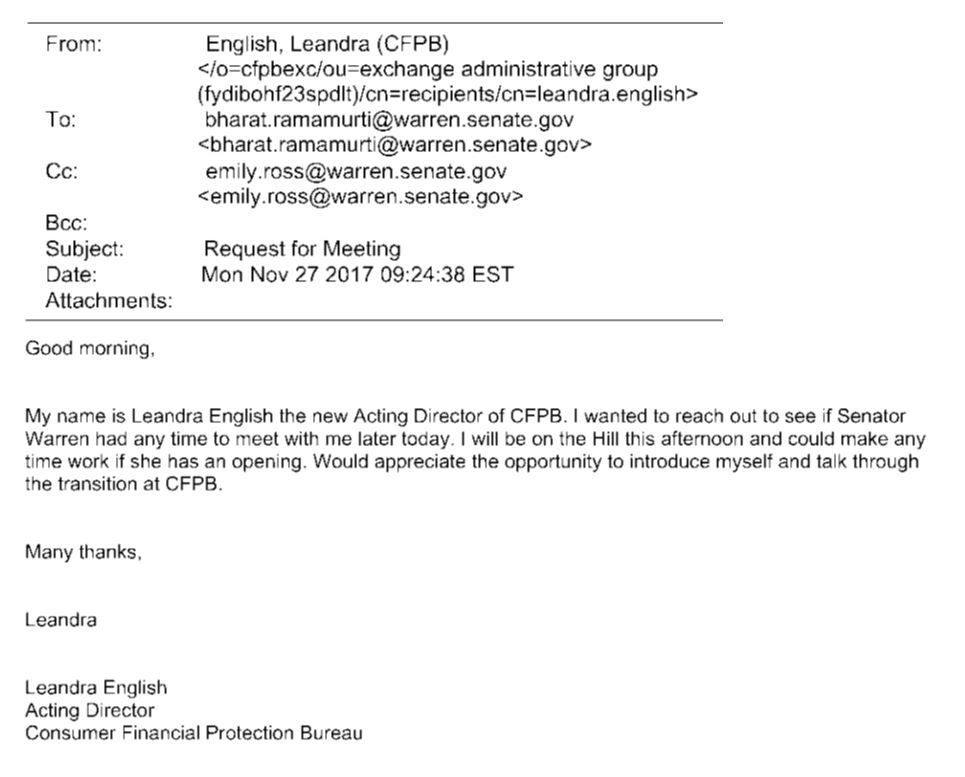

View the Letter Concerning Mr. Rettig’s Nomination Below

James Valvo is Counsel and Senior Policy Advisor at Cause of Action Institute. He is the principal author of Evading Oversight. You can follow him on Twitter @JamesValvo.