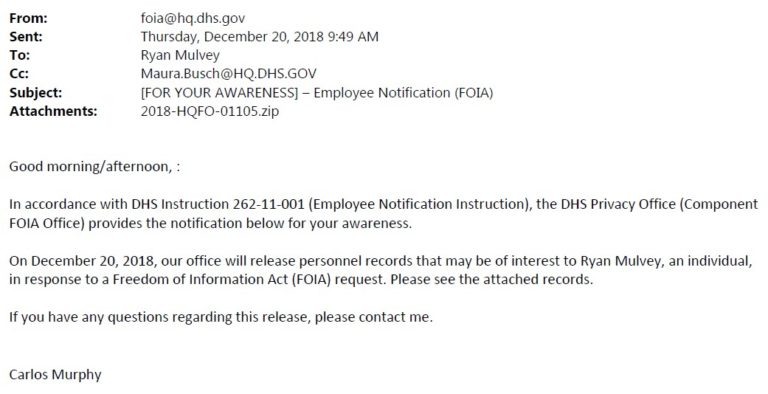

Earlier today, Cause of Action Institute (CoA Institute) received a misdirected email from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that apparently was intended to serve as a notification to an unidentified agency employee that certain personnel records were to be released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

The “awareness” email indicated that employee-related records were scheduled to be released in response to a FOIA request. It also identified the name of the FOIA requester—a CoA Institute employee—and included an attached file containing the records at issue. The email was issued “[i]n accordance with DHS Instruction 262-11-001,” which is publicly available on the DHS’s website and appears to have been first issued at the end of February 2018.

Under Instruction 262-11-001, the DHS is required to “inform current [agency] employees when their employment records . . . are about to be released under the FOIA.” “Employment records” is defined broadly to include any “[p]ast and present personnel information,” and could include any record containing personal information (e.g., name, position title, salary rates, etc.). Copies of records also are provided as a courtesy to the employee.

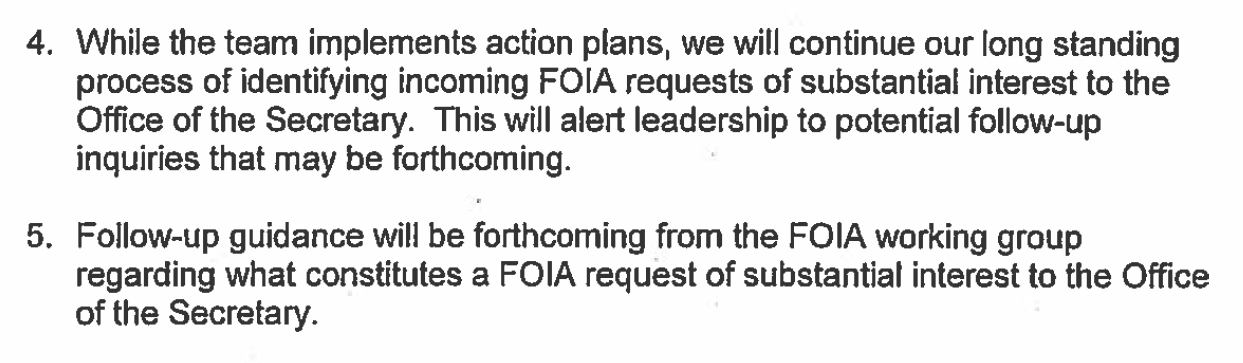

The DHS instruction does not attempt to broaden the scope of Exemption 6, and it recognizes that federal employees generally have no expectation of privacy in their personnel records. More importantly, the policy prohibits employees from interjecting themselves into the FOIA process. This sort of inappropriate involvement has occurred at DHS and other agencies in the past under the guise of “sensitive review,” particularly whenever politically sensitive records have been at issue.

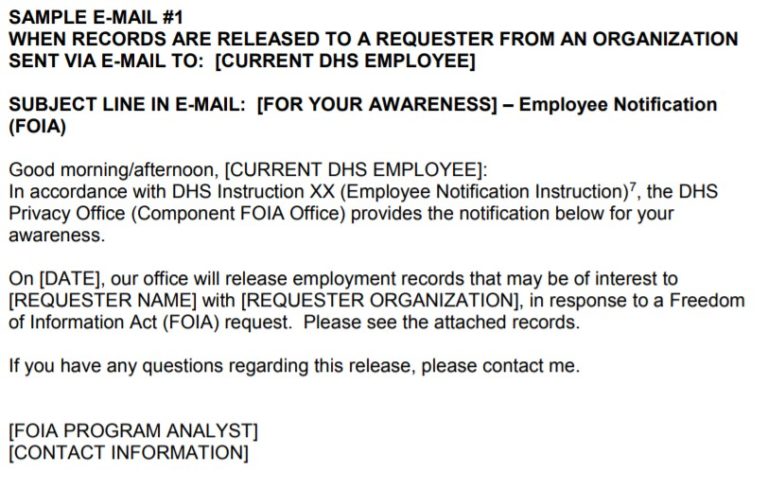

Nevertheless, the DHS “awareness” policy still raises good government concerns. As set forth in the sample notices appended to the instruction, agency employees are routinely provided copies of responsive records scheduled for release, as well as the names and institutional affiliations of the requesters who will be receiving those records.

To be sure, FOIA requesters typically have no expectation of privacy in their identities, and FOIA requests themselves are public records subject to disclosure. There are some exceptions. The D.C. Circuit recently accepted the Internal Revenue Service’s argument that requester names and affiliations could be withheld under Exemption 3, in conjunction with I.R.C. § 6103. Other agencies, which post FOIA logs online, only release tracking numbers or the subjects of requests. In those cases, a formal FOIA request is required to obtain personally identifying information.

Regardless of whether the DHS policy is lawful, it is questionable as a matter of best practice. Proactively sending records and requester information to agency employees could open the door to abuse and retaliation, particularly if an employee works in an influential position or if a requester is a member of the news media. The broad definition of “employee record” also raises questions about the breadth of implementation.

Finally, there are issues of fairness and efficiency. If an agency employee knows that his records are going to be released, is it fair to proactively disclose details about the requester immediately and without requiring the employee to file his own FOIA request and wait in line like anyone else? The public often waits months for the information being given to employees as a matter of course, even though the agency admits that there are no cognizable employee privacy interests at stake.

More importantly, an agency-wide process of identifying employees whose equities are implicated in records and individually notifying them about the release of their personal details likely requires a significant investment of agency resources. Would it not be more responsible to spend those resources on improving transparency to the public at large? To reducing agency FOIA backlogs? Notifying employees whenever their information is released to the public is likely only to contribute to a culture of secrecy and a further breakdown in the trust between the administrative state and the public.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute

CoA Institute Highlights Deficiencies in Proposed Rule to Shift Burdensome Costs of At-Sea Monitoring to Commercial Fishermen

The New England Fishery Management Council (NEFMC), in coordination with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), seeks to approve and implement a controversial set of regulatory amendments that would create a new industry-funding requirement for at-sea monitoring in the Atlantic herring fishery and, moreover, create a standardized process for introducing similar requirements in other New England fisheries. Under the so-called Omnibus Amendment, the fishing industry would be forced to bear the burdensome cost of allowing third-party monitors to ride their boats in line with the NEFMC’s supplemental monitoring goals. This would unfairly and unlawfully restrict economic opportunity in the fishing industry.

Learn More