We began our series of blog posts by examining the history, purpose, and limitations of the Antiquities Act of 1906, 54 U.S.C. §§ 320301 – 320303 (“Antiquities Act” or the “Act”) (here and here), followed by a discussion of how the Act fits within the variety of other frameworks for protecting and using public lands (here and here) and the variety of statutory frameworks and federal government programs that are used to manage the jurisdictional waters of the United States. (here and here). We also shared a copy of the comment we submitted to the Department of the Interior in which we outlined our investigative activity relative to the Bears’ Ears National Monument. This week we review the procedural history of the designation of the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument, also referred to here as the Atlantic Monument, which was made by President Obama on September 15, 2016 (“Proclamation”), and show that certain, privileged, non-governmental entities were granted access to detailed information on the forthcoming monument and allowed input into the designation, while other stakeholders—notably those with specific legal authority, such as Regional Fishery Councils—were denied input and access.

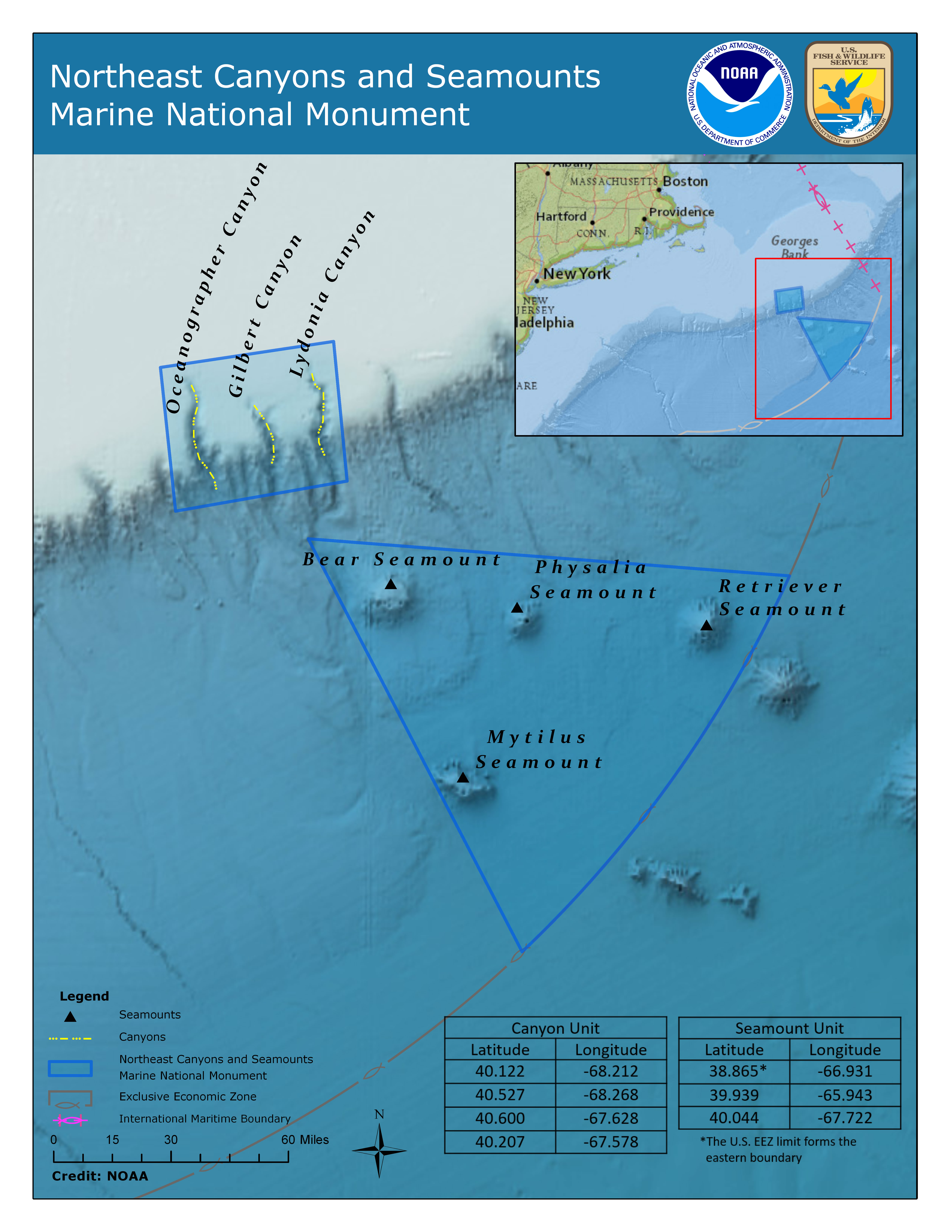

The Atlantic Monument includes the Oceanographer, Gilbert, and Lydonia canyons, which are located at the edge of the geological continental shelf, and the Bear, Physalia, Retriever, and Mytilus sea mounts, which are located farther offshore at the start of the New England Seamount chain.

The Proclamation provided the following justifications for the designation: (1) the historical value of the maritime trades, especially fishing, to the cultural roots of New England; (2) the abundance of deep sea corals, fish, whales, and other marine mammals; and (3) long-time scientific study of the area using research vessels, submarines, and remotely operated underwater vehicles for deep-sea expeditions.

The Proclamation purported to prohibit the following activities, effective immediately:

- Oil, gas, minerals, or other energy exploration, development, or production;

- Poisons, electrical charges, or explosives to collect or harvest a “monument resource;”[1]

- Releasing an “introduced species;”[2]

- Removing a “monument resource” except as provided under “Regulated Activities;”

- Construction or damaging submerged lands (except for scientific instruments or submarine cables);

- Commercial Fishing; and

- Possessing commercial fishing gear unless stowed during “passage without interruption” through the monument.

In addition, the following activities are to be regulated:

- Research and scientific exploration;

- Education, Conservation, and Management;

- Anchoring scientific instruments;

- Recreational fishing;

- Commercial fishing for red crab and American lobster for up to 7 years;

- Sailing, and bird or mammal watching; and

- Submarine cables.

Note that these restrictions do not apply to any person who is not a citizen, national, or resident alien of the United States, unless in accordance with international law. As we explained in our May 22, 2017 blog post, within the EEZ, in which the Atlantic Monument is located, the United States has only limited sovereign rights, and thus international law still applies, limiting the ability of an American President to extend prohibitions to non-Americans.

In light of the stated justification for the Atlantic Monument, it is curious that certain traditional, culturally-significant, and highly-regulated activities, such as commercial fishing, were prohibited; while others, such as recreational fishing, were to be regulated; and some, such as commercial fishing for red crab and American lobster, were granted a seven-year stay of execution—bearing in mind that none of these classifications or limitations even apply to non-Americans.[3] These discrepancies, as well as peculiarities in the procedural history of the Atlantic Monument, were among the bases for a series of FOIA requests that CoA Institute submitted in October 2016, in which we requested records from NOAA and the Council on Environmental Quality (“CEQ”) relating (among other things) to the designation of the Atlantic Monument and to the justification for the unequal treatment of stakeholders and the opaque process surrounding the designation of the Atlantic Monument. The submitted FOIA requests include the following:

- NOAA FOIA Request regarding the Rhode Island Town Hall Meeting;

- NOAA FOIA Request regarding potential Marine Monuments in the Atlantic;

- NOAA FOIA Request regarding Congressional Records;

- CEQ FOIA Request regarding the Antiquities Act; and

- CEQ FOIA Request regarding Third-Party Communications.

To-date NOAA and CEQ have released only a portion of the requested documents. However, even the initial interim releases show that, despite claims that the Atlantic Monument is the product of “an extensive year-long public process,” the designation of the Atlantic Monument was a predetermined decision that allowed for limited public input to appease public backlash.

The following history, derived from the partial responses to CoA Institute’s FOIA requests and other publicly available documents, is illustrative:

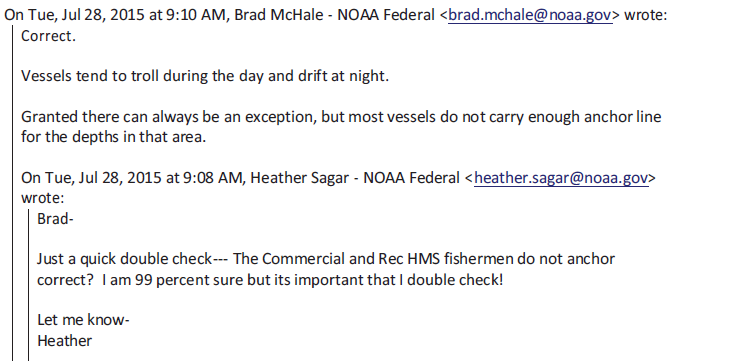

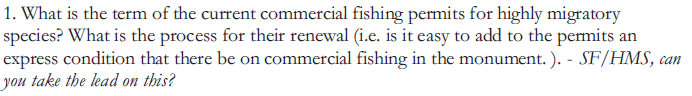

In March 2015, the Conservation Law Foundation (“CLF”) and Natural Resources Defense Council (“NRDC”) published an Issue Brief that advocated for “permanent protection” of New England’s canyons and seamounts. By July 2015, NOAA personnel in the Fisheries Service were already discussing the details of which activities should be prohibited post-Proclamation, such as whether the Proclamation should include an exception to the prohibition on fishing for highly migratory species (“HMS”), such as tuna, swordfish, marlin, and a variety of sharks. Although the discussion confirmed that neither commercial nor recreational fishermen of HMS anchor their boats ; and, in fact, most vessels do not carry enough anchor line for the depths in the area, ultimately HMS commercial fishing was prohibited.

In August 2015, the Conservation Law Foundation forwarded to NOAA an invitation to an event scheduled for September 2, 2015 at the New England Aquarium regarding deep sea canyons and seamounts located off the coast of Cape Cod and expressing commitment to “real and significant conservation in New England and . . . ensuring the timely completion of a good and effective ocean plan—the first in the U.S.” The message made no mention of the New England Regional Fishery Management Plan that had long been in place under the Magnuson-Stevens Act.

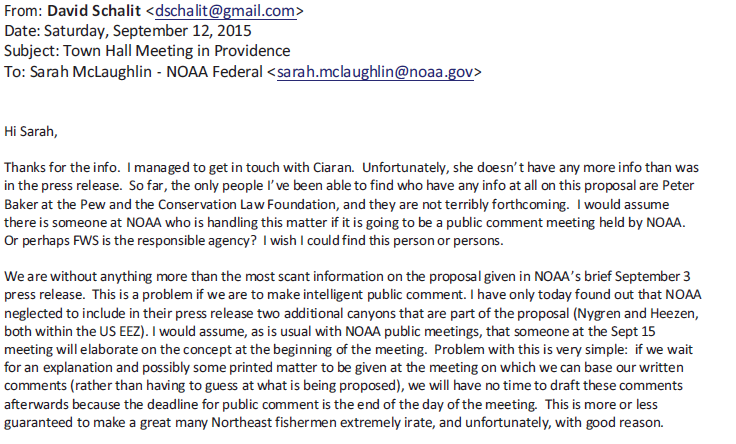

The following day, September 3, 2015, NOAA issued a broad invitation to participate in a Town Hall meeting scheduled for September 15, 2015—just 12 days after the announcement—to discuss “permanent protections” for three deep sea canyons and four seamounts off the coast of New England. The invitation did not mention designation of a National Monument nor that the meeting would be the only event at which to present feedback. It provided a deadline for submitting written comments to a special NOAA e-mail address, which was set for the same day as the Town Hall meeting. No proposal or details were included with the invitation.

It appears that certain privileged, non-governmental entities that had the inside track on the proposal, including the Pew Research Center and the Conservation Law Foundation, had more information about the proposal before the Town Hall meeting than NOAA was able, or willing, to make available to stakeholders. The lack of information available to local stakeholders hindered their ability to provide meaningful commentary.

NOAA, however, had prepared a briefing document as early as July 2015 that included much relevant information and identified the conflict between the monument proposal and the fishery management councils’ activities. The briefing document also “red flagged” the anticipated objections of various fishermen on the basis that their fishing was not harmful to the area. As of July 2015, the proposal allowed commercial pelagic fishing (i.e., fishing in the water column)—an activity that was ultimately forbidden.

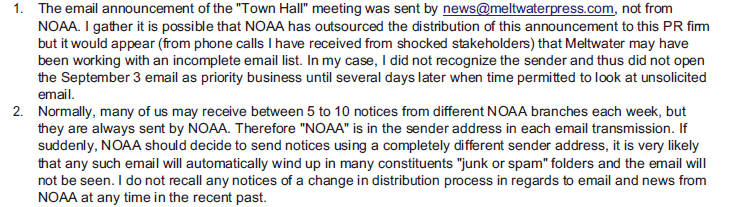

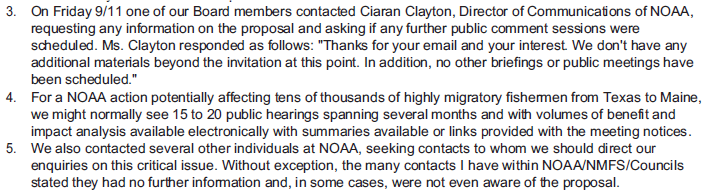

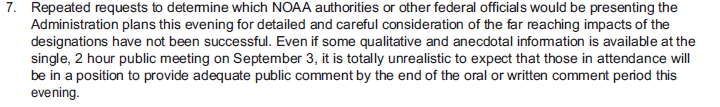

Before the Town Hall meeting, NOAA was advised of specific shortcomings in the notice process that further compromised the ability of local stakeholders to provide meaningful input and that buttressed the impression that the entire process was undemocratic and designed to bypass the extensive multi-year effort to protect marine resources. For example:

- In contrast to NOAA’s standard practice of sending email messages from “@noaa.gov,” the e-mail message announcing the Town Hall meeting was sent from news@meltwaterpress.com, which led recipients to fail to recognize that the message included an important announcement and increased the potential for the message to be caught in a spam-blocker;

- In response to a request for information before the Town Hall meeting, the requester was told that no information beyond the press release was available and no additional briefings or public meetings were scheduled, in contrast to the typical process of holding 15-20 public hearings and providing information electronically.

….

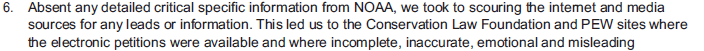

- However, consistent with the experience of other stakeholders, on-line research of the proposal led to the Conservation Law Center and PEW websites, where electronic petitions were available along with inaccurate and misleading information.

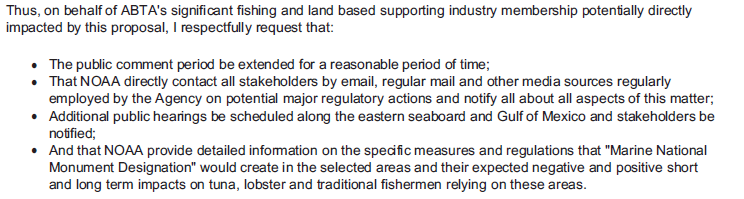

- As a result of the patent deficiencies (whether by design or omission) in the public comment process, the writer requested from NOAA an extended comment period, additional public hearings, and detailed information on the specific proposed measures. It appears that no such opportunity for meaningful feedback was ever provided.

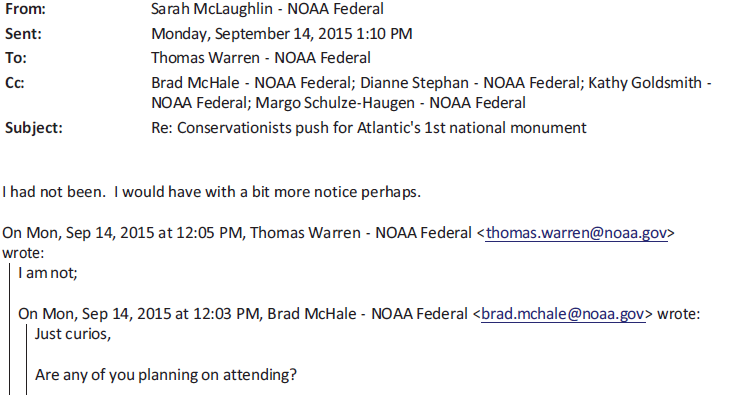

The lack of proper notice for the town hall meeting was not just a sticking point for fishermen who were unable to attend, but even created an impediment to attendance for NOAA personnel.

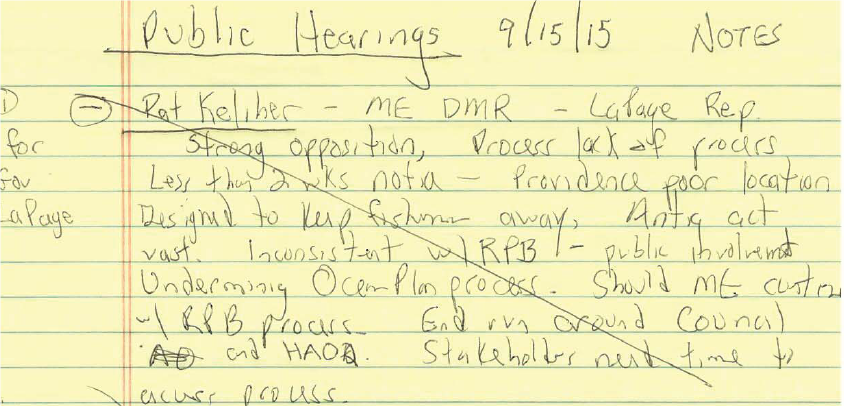

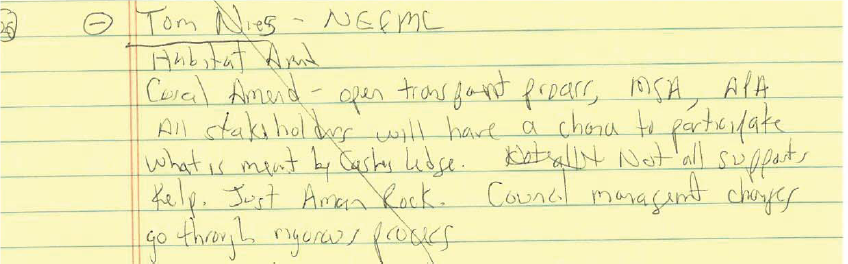

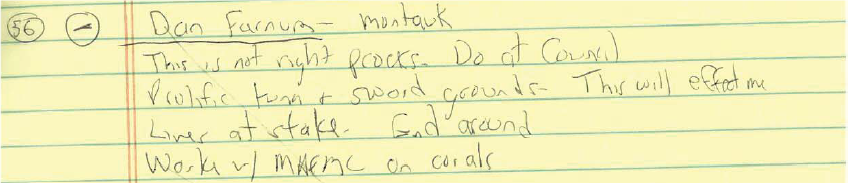

The lack of notice was a contentious issue at the Town Hall meeting, as was the Providence, Rhode Island location, which appeared to have been chosen to keep fishermen away.

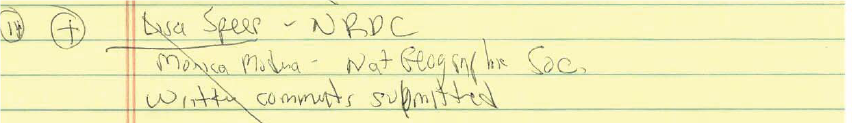

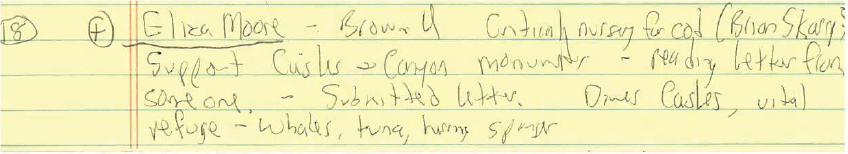

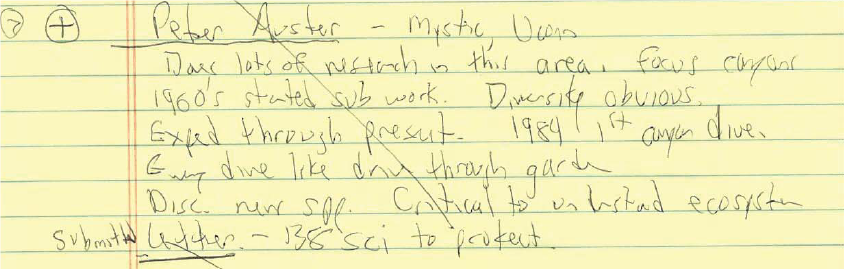

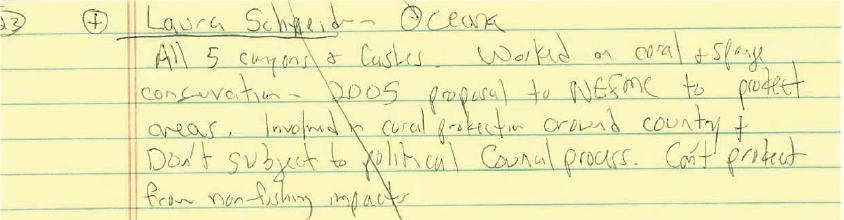

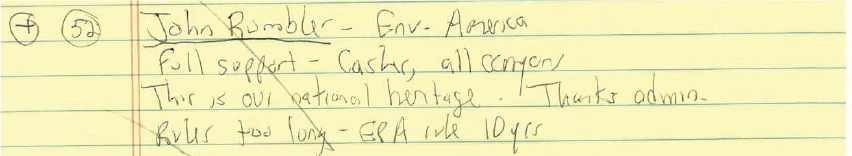

By contrast, representatives of academia, Brown University and the University of Connecticut, and special interest groups, Pew and NRDC, remarked that they had already submitted written comments on the proposal. They, apparently, knew enough about the proposal before the meeting to draft comments and submit them ahead of time.

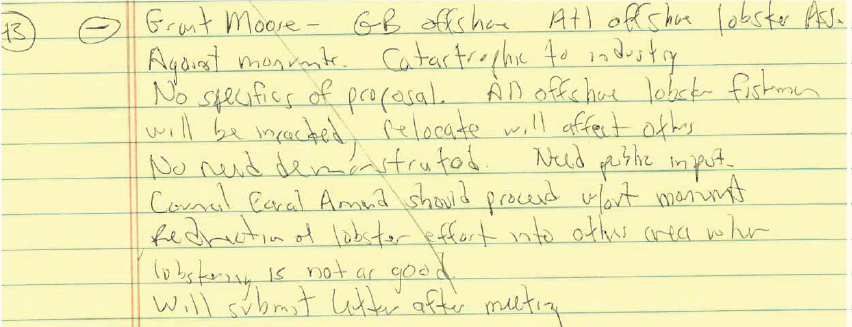

Others—notably fishermen and local businesses—were not privy to specifics of the proposal until they arrived at the Town Hall meeting, and, even then, were provided inadequate details.

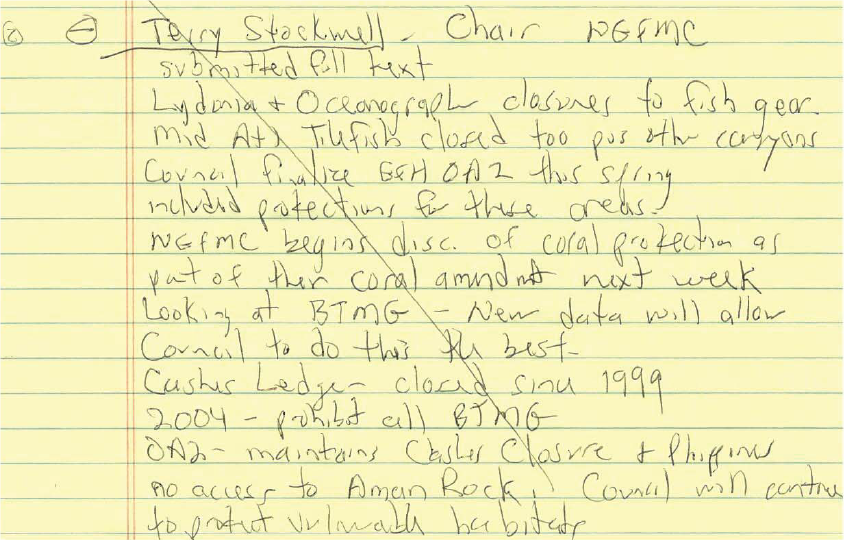

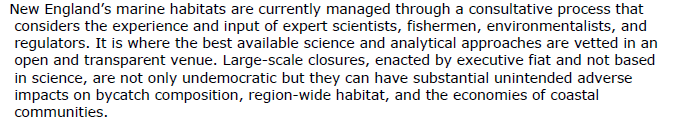

The exclusion of the Fishery Management Council from meaningful input apparently was consistent with a desire by some to bypass the “too long” democratic process.

Comments by stakeholders with intimate knowledge of how the area is managed told a different story—the Lydonia and Oceanographer canyons were already closed to fishing gear . . .

. . . the Fishery Management Council process is based on science and abundant data . . .

. . . the Council process is rigorous. . .

. . .and the “pristine” condition of the areas shows that the areas have been well-managed.

Stakeholders who must actually live with the effects of the Atlantic Monument also commented that there are public impacts from the proposed monument—to jobs and other fishing areas that must be, and have not been, considered. As one commenter stated—there are lives at stake.

The full text of the statement of the New England Council Chairman, explaining the history of the Council’s actions, and the design of coral management zones, can be found here.

These spoken comments were consistent with written comments submitted immediately before or shortly after the Town Hall meeting.

Written comments provided after the hearing highlighted certain factual inaccuracies in the presentation in support of the monument, such as:

- The claim that there was increased fishing pressure in the designation areas when, in fact, the number of boats actually fishing had fallen dramatically (by 2/3 or more);

- The Annual Catch Limit is well below the Overfishing Limit;

- The fishing methods described at the September 2015 Town Hall meeting do not resemble the methods actually used;

- Sword fish and squid fishing gear does not come anywhere close to the bottom;

- Thousands of square miles of New England waters have already been closed to fishing via democratic process—in contrast to the undemocratic process used to designate the monuments.

Written comments also reiterated the complaint that the process of designating the monument lacked transparency, including:

- The lack of notice for the town hall meeting;

- The two-minute limit on oral comments;

- The lack of parameters (time frame, review process, etc.) for written comments;

- The lack of ability of NOAA staff to answer questions;

- The pervasive misrepresentation of existing environmental protections and conditions; and

- The lack of specifics on the proposal—no boundaries, no regulatory provisions, no depth contours, and no evidence of need or benefit to closing the area.

Meanwhile, as the fishermen were begging for due process and the Council was pleading to be allowed to do its job, it appears that the Administration was continuing to work with certain, privileged, non-governmental entities toward announcing the monument designation at the 2015 Our Oceans Conference, scheduled to take place in Valparaiso, Chile or October 5-6, 2015. Notably, this plan was known among the privileged entities before the Town Hall Meeting, a fact that they took care to keep quiet.

The “potential collusion” of these outside interests in the apparently pre-ordained monument designation was of concern to the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Natural Resources, which held an oversight hearing on the potential designation of marine national monuments on September 29, 2015—only 6 days before the Our Oceans announcement was to take place.

Throughout 2016, objections to establishing a marine monument in the Atlantic were made by stakeholders who had intimate knowledge of the area as well as their life’s work at risk. Like the earlier commenters, they objected to the lack of transparency, democratic process, accurate data, and coordination with existing—and effective—management plans.

These calls went unheeded and the Atlantic Monument was proclaimed on September 15, 2016. Nevertheless, and notwithstanding the initial plan to announce its designation at the Our Oceans Conference in October 2015, throughout 2016, there remained considerable confusion within NOAA as to what the monument would entail, including very basic questions such as:

the types of fisheries that are in the monument area;

whether fishing permits are required, the term of fishing permits, and the effect of the designation on existing permits;

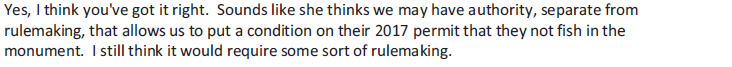

whether conditions could be placed on permits by NOAA, or whether a rule-making would be required

Ultimately, they concluded that a rulemaking would be required:

The need for a rulemaking also raises the critical question of whether the Administration ever had the legal authority to implement a monument in the Atlantic Ocean in the first place. But, more on that later . . . Our series will continue next week with an analysis of the legal issues arising from the imposition of a Marine National Monument in an area that is already subject to a comprehensive regulatory scheme.

Any questions, commentary, or criticisms? Please e-mail us at kara.mckenna@causeofaction.org and/or cynthia.crawford@causeofaction.org.

Cynthia F. Crawford is a Senior Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.

Kara E. McKenna is a Counsel at Cause of Action Institute. You can follow her on Twitter @Kara_McK

[1] This term is not defined in the Proclamation.

[2] This term is not defined in the Proclamation.

[3] Citizen, national, or resident alien of the United States.