Earlier this week, Democrats on the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee (“OGR”) released details about how officials from the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) admitted to subjecting politically sensitive Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) requests to layers of extra scrutiny, including review by political appointees. OGR Ranking Member Elijah Cummings even asked Chairman Trey Gowdy to issue a subpoena compelling the EPA to hand over various records documenting its FOIA processes.

Since Cause of Action Institute’s (“CoA Institute’s) coverage of this issue on Monday, there have been two important developments. First, on Tuesday, Chairman Gowdy denied OGR Democrats their request for a subpoena. Second, and more importantly, reports have revealed that Kevin Minoli, the EPA Principal Deputy General Counsel and Designated Agency Ethics Official, sent a letter to OGR Democrats on Sunday, arguing that the agency’s sensitive review policies actually originated with the Obama Administration.

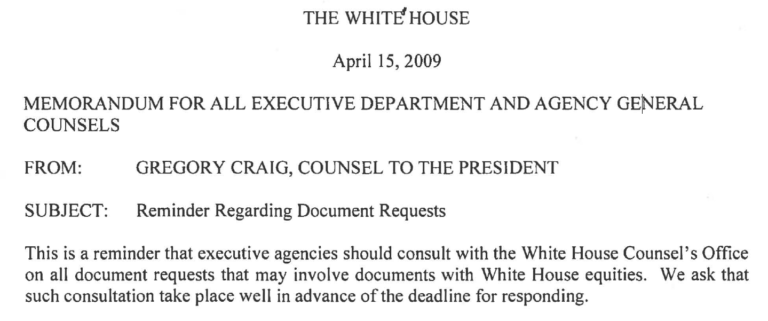

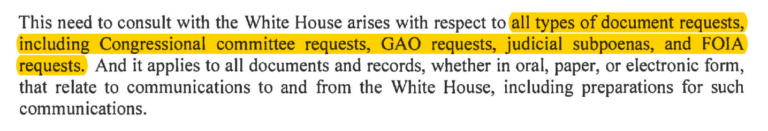

According to Minoli, the EPA created a “FOIA Expert Assistance Team,” or “FEAT,” in 2013 to provide “strategic direction and project management assistance” on “complex FOIA requests.” Minoli explained that a FOIA request could be classified as “complex,” for FEAT purposes, if someone in the agency’s leadership requested it to be so. FEAT coordinated “White House equities” review and also alerted the Office of Public Affairs, as well as “senior leaders” within the EPA, of particularly noteworthy requests through its so-called “awareness review” process.

The EPA’s latest clarification vindicates CoA Institute’s repeated warnings (here and here) not to let political judgments about the Trump EPA’s policy agenda interfere with understanding and criticism of long-standing problems of FOIA administration, including the politicization that inevitably results from “sensitive review” processes. To be sure, it appears the Trump Administration has worsened the problem, particularly at the EPA. But the groundwork for this sort of FOIA politicization was laid by President Obama. Indeed, Minoli claims OGR’s investigative work during the Obama-era was part of the then-Administration’s impetus for creating FEAT.

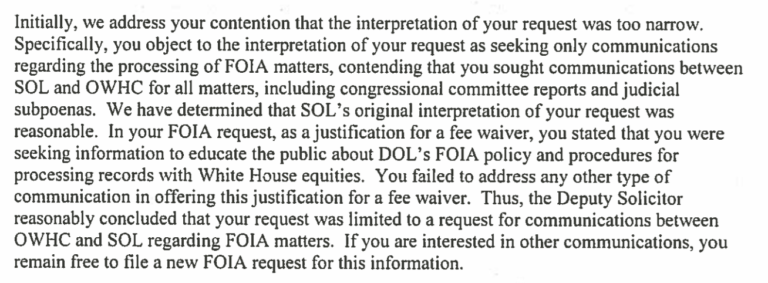

Regardless of which party or president is responsible for introducing FOIA sensitive review at the EPA or any other agency, the practice still raises serious concerns. Although alerting or involving political appointees in FOIA administration does not violate the law per se—and may, in rare cases be appropriate—there is never any assurance that the practice will not lead to severe delays of months and even years. At its worst, sensitive FOIA review leads to intentionally inadequate searches, politicized document review, improper record redaction, and incomplete disclosure. When politically sensitive or potentially embarrassing records are at issue, politicians and bureaucrats will always have an incentive to err on the side of secrecy and non-disclosure.

Considering these developments, CoA Institute has submitted a FOIA request to the EPA seeking further information about FEAT and the agency’s sensitive review policy. We will continue to report on the matter as information becomes available.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.