Cause of Action Institute (CoA Institute) yesterday submitted a public comment to the Department of the Interior (DOI), criticizing the agency’s proposed revisions to its Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) regulations. DOI’s amendments, which were published in the Federal Register in the final days of 2018, have already received negative attention from media sources, which suggest that the changes are intended to frustrate public access to records. The government, for its part, claims that the revisions are necessary to deal with the marked increase of requests during the Trump Administration and to promote efficiency in the administration of the DOI FOIA program.

CoA Institute’s comment covers a variety of topics, but three are worth highlighting. First, DOI seeks to prohibit intra-agency forwarding of “misdirected” requests. But this proposal runs afoul of clear statutory directives. Under Section 552(a)(6)(A)(ii) of the FOIA, the twenty working-day time frame for responding to a request begins to run once a request is received by an “appropriate component,” that is, the agency office likely to maintain responsive records. In computing those twenty days, an agency is permitted no more than ten days to redirect any requests that have been sent to the wrong bureau or component. In other words, so long as the agency has received the request, it is already under an obligation to begin processing it. This “routing requirement” was introduced by the OPEN Government Act of 2007, and it has been consistently interpreted by the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Office of Information Policy as prohibiting agencies from refusing to honor requests that have merely been sent to an incorrect office.

Beyond the legal deficiency in the elimination of intra-agency forwarding, it is not clear whether the change would even promote the efficiency goals envisioned by the rulemaking. By refusing to forward misdirected requests, DOI may instead create an incentive for requesters to submit nearly-identical requests to multiple bureaus. That could increase the FOIA backlog. The elimination of intra-agency forwarding also would unfairly require requesters to identify the precise locations where the agency should conduct its search for responsive records.

Second, DOI wants to require requesters to describe the “discrete, identifiable agency activity, operation, or program” that their records requests concern. Such ambiguous language imposes an unacceptable burden on requesters, who need only provide a “reasonable description” of the records they seek such that a knowledgeable professional within the agency could locate responsive material with reasonable effort. DOI would similarly refuse to accept “broad requests,” despite the fact that OIP has advised agencies for over thirty years that “[t]he sheer size or burdensomeness of a FOIA request, in and of itself, does not entitle an agency to deny that request on the ground that it does not ‘reasonably describe’ records[.]”

Third, and finally, DOI proposes to change its regulatory definition of a “record” by deviating from the statutory text and importing language from the Privacy Act. CoA Institute has diligently followed developments in how the government defines a “record” under the FOIA. In October 2018, we filed a lawsuit against the Department of Justice, challenging guidance that would permit agencies to break a single record into multiple smaller records, redacting information that should otherwise be public and that would not meet allowable exemptions under the FOIA statute. DOI’s proposed rule follows this troubling guidance, particularly in its use of the Privacy Act’s definition of a record as “any item, collection, or grouping of information.”

DOI’s proposed definition of a record also includes items that are “reasonable encompassed by [a] request.” This phrase seems to contemplate a relationship between the definition of a record and an individual request. Yet a requester may only seek the disclosure of pre-existing records. To allow the definition of a record to vary depending on any particular request would move away from an objective standard and allow FOIA officers too much discretion in the processing of potentially responsive materials.

CoA Institute is hopeful that DOI will accept these constructive comments, and others, and make any necessary corrections before publishing its final rule.

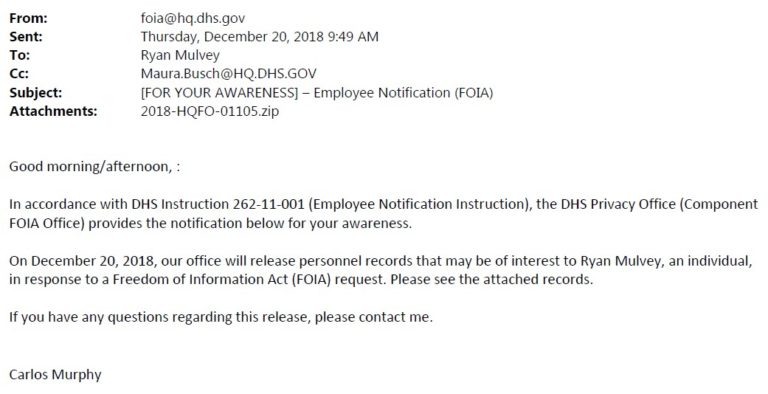

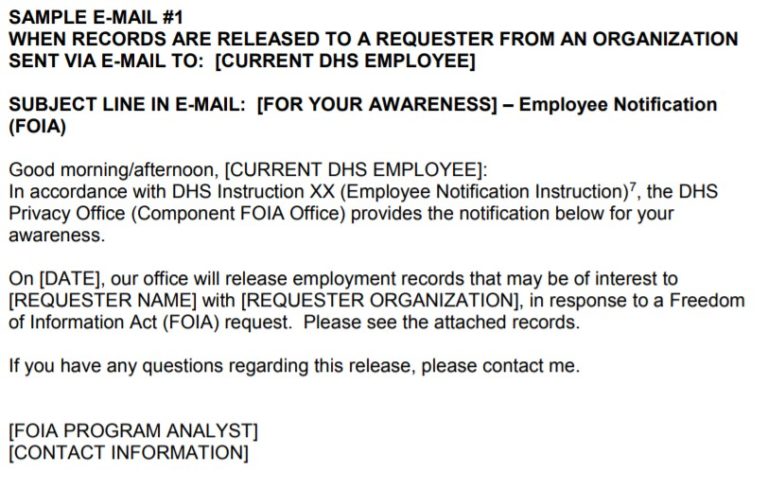

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute

Loading...

Loading...