The last-ditch coup by Richard Cordray was orchestrated despite apparent pushback from CFPB’s top attorney

Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) has uncovered documents that reveal Richard Cordray and his lieutenants, in Cordray’s last days as director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (“CFPB”), scrambled to plan a gambit to usurp the president’s appointment authority and allow Cordray to name his own successor.

Cordray announced on November 15, 2017 that he would be stepping down as director of the CFPB, presumably to run for governor of Ohio. Later that same day, the president announced his intention to appoint an acting director until a new director could be nominated and approved by the Senate. Here’s where things get interesting. On November 24, 2017, Cordray named the agency’s chief of staff, Leandra English, as the deputy director of the CFPB. Then, he announced his resignation and tapped English as the acting director.

President Trump ignored this attempted unlawful action and appointed his own acting director, Mick Mulvaney. Then the next day, the general counsel of the CFPB issued an opinion supporting the president and holding Mulvaney as the acting director.

Accordingly, as General Counsel for the Bureau, it is my legal opinion that the President possesses the authority to designate an Acting Director for the Bureau under the FVRA, notwithstanding § 5491(b)(5).

English, however, refused to back down, creating the absurd situation where a government agency had two people claiming to be acting director. She sued in federal court, asking Judge Timothy Keller to make her acting director. The court, however, denied her request, holding that “[d]enying the president’s authority to appoint Mr. Mulvaney raises significant constitutional questions.” The agency, relying both on the opinion of its general counsel and the court’s decision, has recognized Mulvaney as the leader. The Court case continues. What follows is the result of CoA Institute’s investigation into the final weeks of Cordray’s tenure as director.

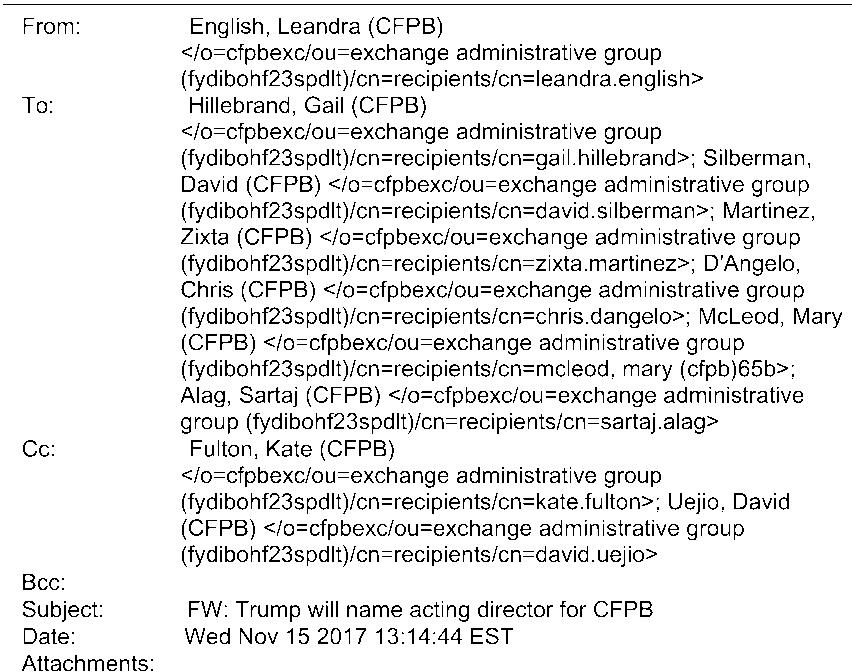

Internal CFPB communications reveal that on November 15, the date Richard Cordray announced his intent to retire, English forwarded Cordray a Politico Pro email that contained a report of the president’s intention to appoint an acting director. A number of top CFPB employees were CC’d on this email, including General Counsel Mary McLeod.

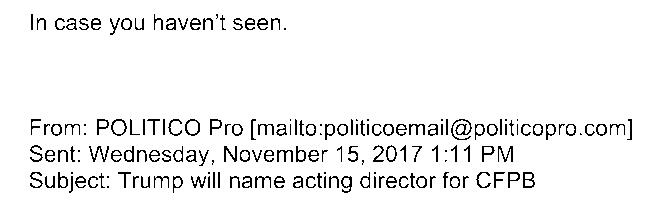

The next substantial action came on November 22, when “RC” (presumably Richard Cordray) circulated an article from creditslips.com that outlines a legal argument for Cordray to appoint his own successor. Just two minutes later, Cordray sent another article from theintercept.com which, relying on the creditslips.com article, posits that David Silberman, then acting deputy director, should succeed Cordray. The article notes “[t]he legal argument that Silberman would become interim director would be greatly improved if Cordray officially named him deputy director[.]” CC’d on both these emails is General Counsel McLeod. The full subject of Cordray’s email includes the line: “Mary [McLeod], need you to have people consider it further please[.]”

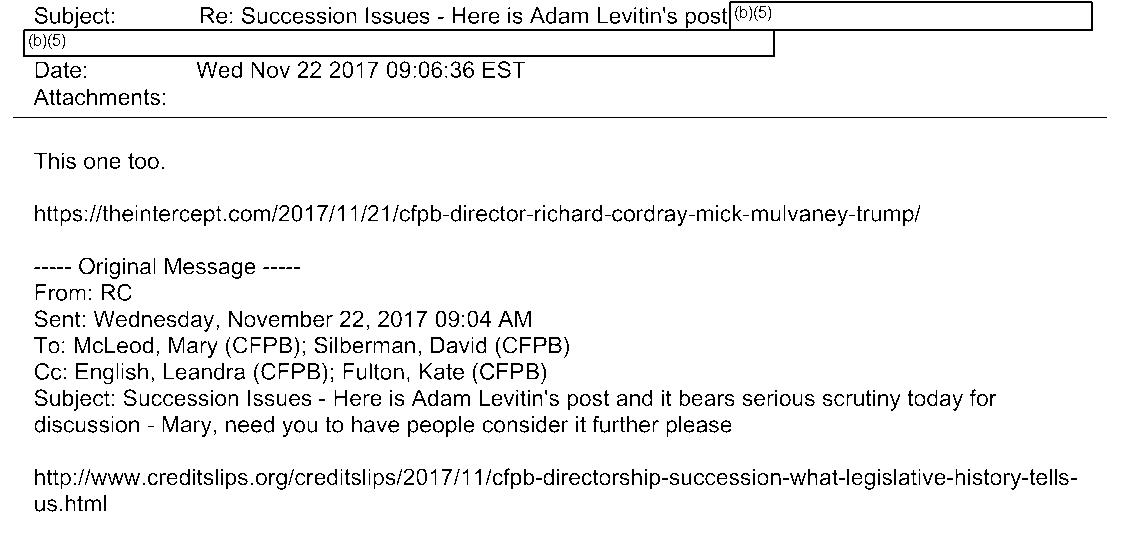

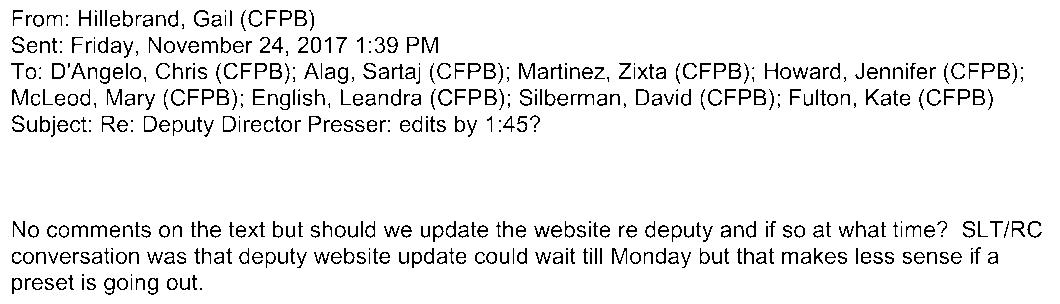

On the day of the formal resignation, November 24, documents revealed a scramble inside CPFB to properly time the gambit. In an email thread titled “Possible presser” sent between Zixta Martinez, associate director for external affairs, Jennifer Howard, assistant director for communications, Kate Fulton, deputy chief of staff,[1] Cordray, and English, the group appears to discuss a document that is distinct from Cordray’s formal resignation announcement. The group is concerned about the resignation going out before this “presser” document which, presumably, was the announcement of Leandra English as deputy director.

Later that day, in Cordray’s final letter to the staff, he made public his intention to name Leandra English as deputy director and his self-proclaimed successor. The email below reveals that the agency wanted to wait until virtually the last minute to put this all into process.

Cordray’s team grappled with when, and in what order, to update the website.

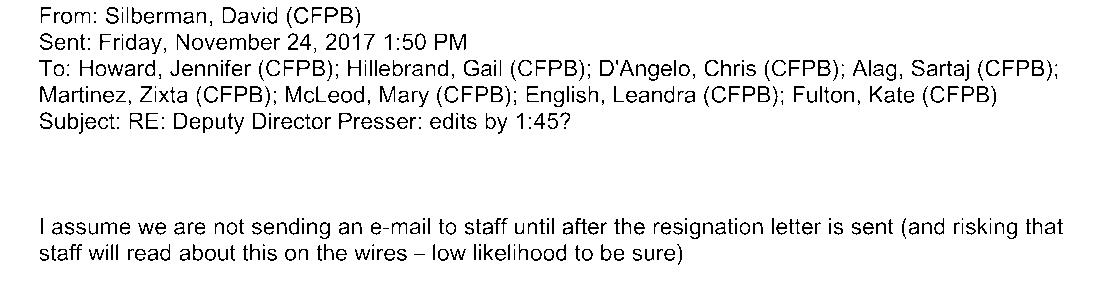

And, finally, discussion of the order of the email to staff and the resignation letter.

English confirms:

The general counsel, Mary McLeod, was obviously aware that this is all going on, given that she was CC’d on virtually all of these emails, including the one above. Yet, in the biggest blow to Cordray’s gambit, General Counsel McLeod sends a letter memo to the CFPB Leadership Team the very next day, November 25, with a concrete conclusion:

I advise all Bureau personnel to act consistently with the understanding that Director Mulvaney is the Acting Director of the CFPB . . . . Accordingly, as General Counsel for the Bureau, it is my legal opinion that the President possesses the authority to designate an Acting Director for the Bureau under the FVRA, notwithstanding § 5491(b)(5).

Elsewhere in her letter, McLeod states, “[t]his confirms my oral advice to the Senior Leadership team[.]” Oral advice that the team ignored when they tried to install English.

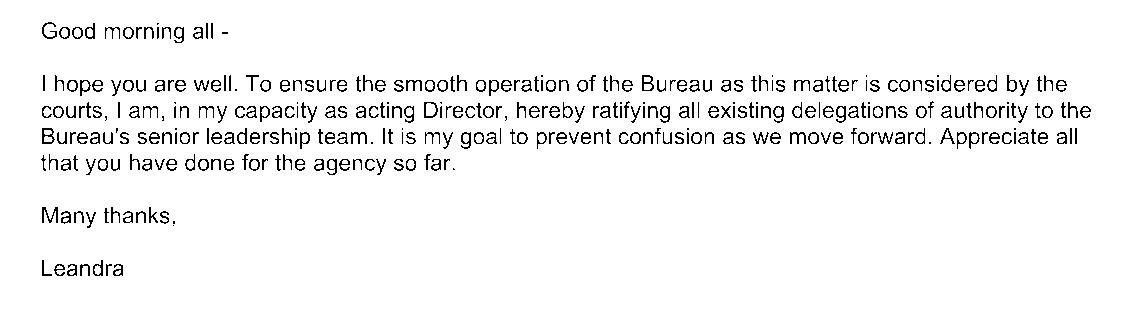

To make matters worse, English continued to send emails claiming to be the Acting Director. The first came in an email to the Senior Leadership Team, which included the General Counsel.

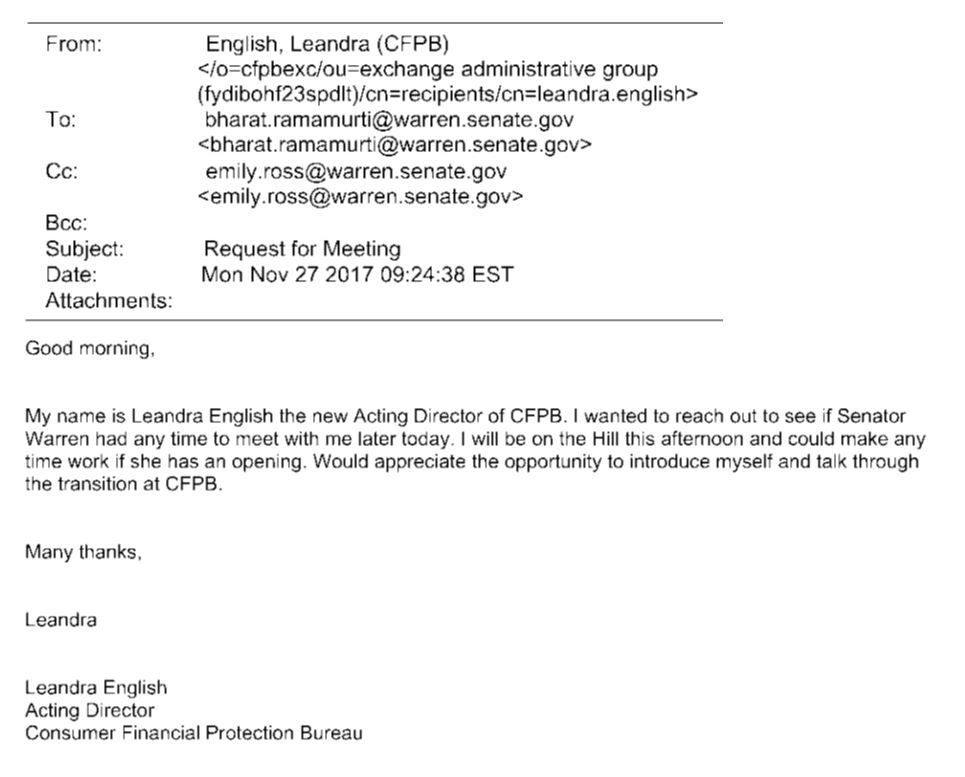

She made the same claim in an email to the staff of Senator Elizabeth Warren:

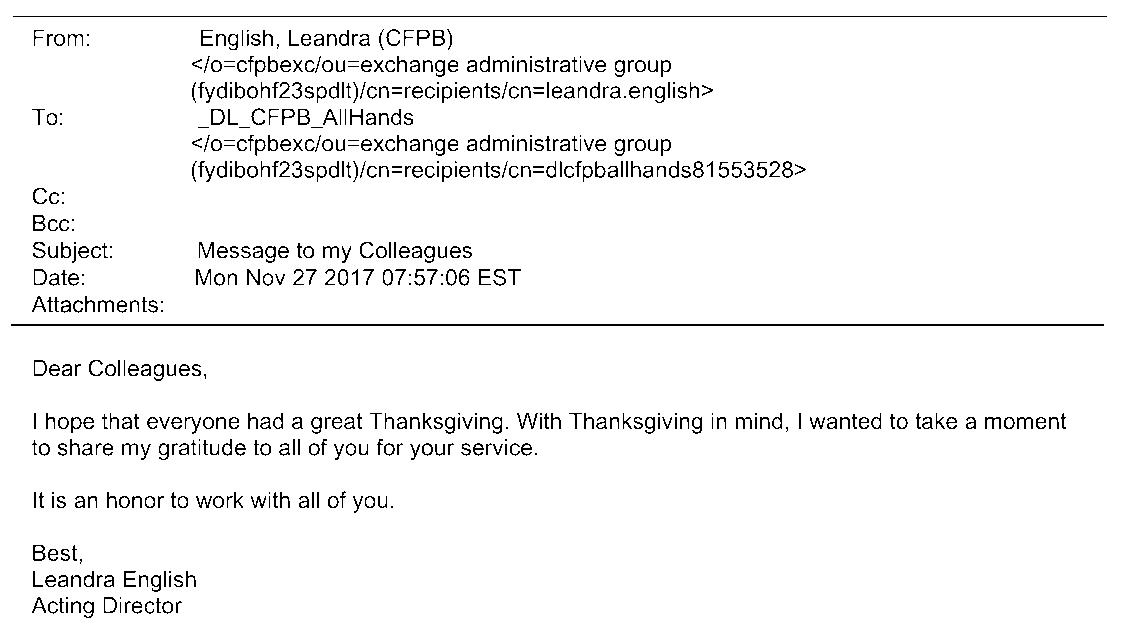

And finally in a staff-wide email.

This brazen attempt to commandeer an entire agency threatens the Constitutional Order. Were Richard Cordray and Leandra English successful, they would have essentially created an agency that fell outside of any of the three branches of government. As D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Brett Kavanaugh stated, the Director of the CFPB holds “enormous power over American business, American consumers, and the overall U.S. economy. [ ] The Director alone decides what rules to issue; how to enforce, when to enforce, and against whom to enforce the law[.]”[3] Judge Kavanaugh concluded, “the Director enjoys more unilateral authority than any other officer in any of the three branches of the U.S. Government, other than the President.”[4] Deciding who wields such awesome power should not happen in a series of harried emails between bureaucrats. It should be decided by the President[5] and, when a permanent successor is ultimately named, the Senate confirmation process.[6]

Eric Bolinder is counsel at Cause of Action Institute.

[1] According to LinkedIn.

[3] PHH Corp v. Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, 839 F.3d 1, 7 (D.C. Cir. 2016), vacated and granted en banc review, Feb. 16, 2017. The D.C. Circuit granted en banc review for this case, which automatically vacates Judge Kavanaugh’s opinion. A decision is still pending.

[4] Id.

[5] See U.S. Const. art. II, § 3, cl. 2. (the Appointments Clause).

[6] This author would like to note he agrees with Judge Kavanaugh that the overall structure of the CFPB is unconstitutional, regardless of who appoints the Director.