Trump’s monument review is as secretive as Obama’s designations

Trump’s monument review is as secretive as Obama’s designations

By Kara McKenna, counsel at Cause of Action Institute

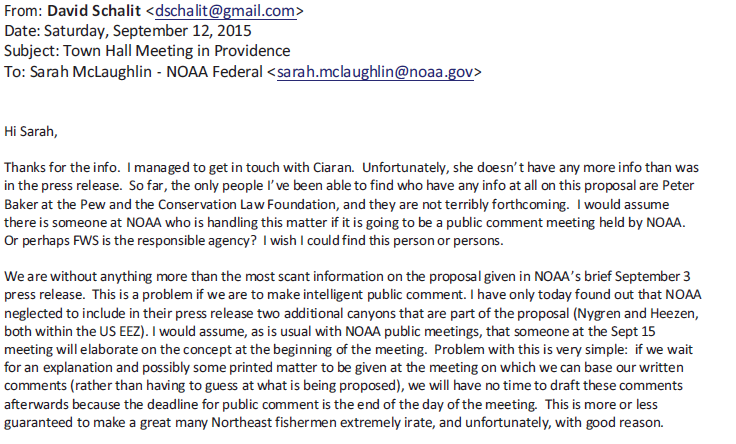

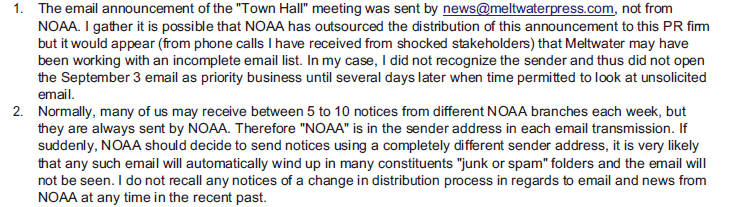

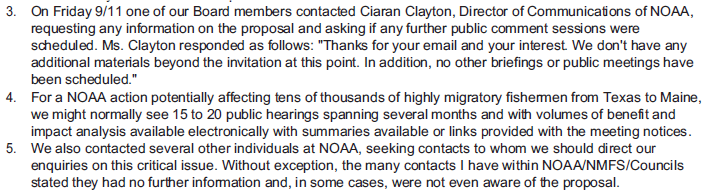

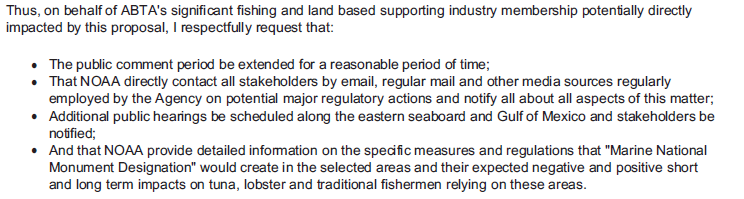

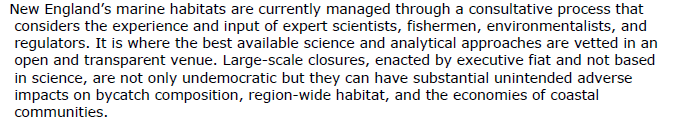

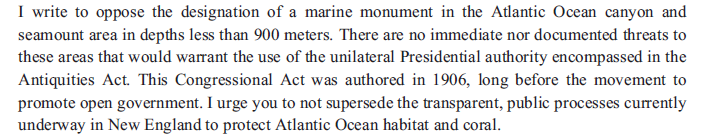

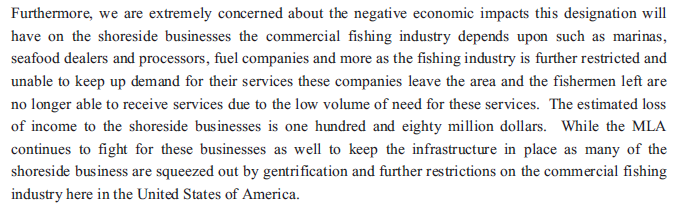

Presidential use of the Antiquities Act is ripe for abuse, as major decisions impacting vast public lands, natural resources, property rights, livelihoods and private industry are left to the sole discretion of the president. After such a unilateral designation, the president does not need to substantiate his decision in any meaningful way, beyond the use of a few magic words on the face of the proclamation.

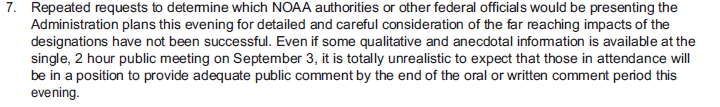

It seemed like a positive step when President Trump in April issued an executive order seeking public input for a review of national monument designations over the last two decades. But it now appears that any hope for additional transparency may have been premature. Read the full article at The Hill