Last week, Judge Emmet Sullivan of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia issued an order denying Cause of Action Institute’s (“CoA Institute”) cross-motion for summary judgment in a Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) brought against the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”). The opinion was long awaited—summary judgment briefing ended over a year-and-an-half ago. Although we do not intend to appeal the decision, it is worth highlighting some issues with Judge Sullivan’s opinion and the IRS’s arguments. The case is a fine example of how courts too frequently defer to agencies when it comes to policing their compliance with the FOIA.

Background: “White House equities” review and FOIA politicization

In March 2014, CoA Institute published a report revealing the existence of a non-public memorandum from then-White House Counsel Gregory Craig that directed department and agency general counsels to send to the White House for consultation all records involving “White House equities” when collected in response to any sort of document request. This secret memo stands in stark contrast to President Obama’s January 2009 directive on transparency, as well as Attorney General Holder’s March 2009 FOIA memo. Although originally praised as setting the bar for open government, the Washington Post eventually described the Obama Administration as one of the most secretive governments in American history.

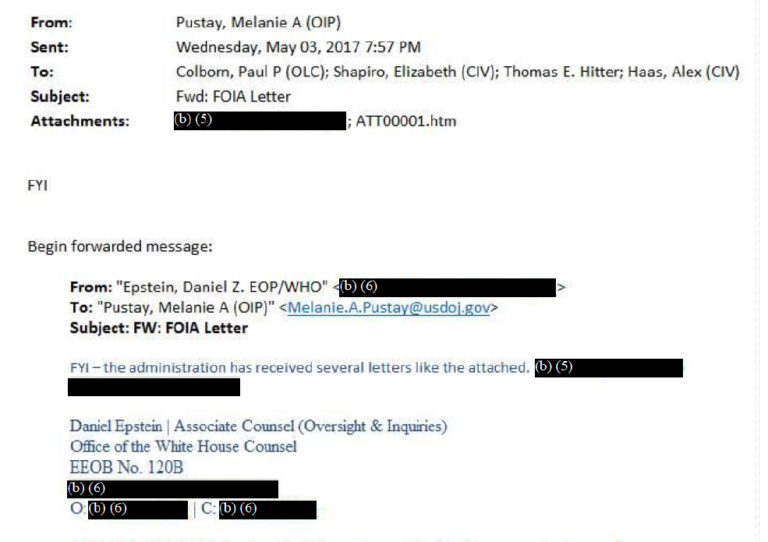

As part of the system of politicized FOIA review established under the “White House equities” policy, whenever a requester sought access to records deemed politically sensitive, potentially embarrassing, or otherwise newsworthy, the agency processing the request would forward copies of those records to a White House attorney for pre-production review. Not only did the entire process represent an abdication of agency responsibility for the administration of the FOIA, but it severely delayed agency compliance with the FOIA’s deadlines. As we have previously suggested, “White House equities” review likely continues under the Trump Administration.

The specific FOIA request at issue in this case, which was submitted to the IRS in May 2013, sought records of communications between IRS officials and the White House reflecting “White House equities” consultations. Similar requests were sent to eleven other agencies. All those agencies produced the requested records; only the IRS failed to locate a single relevant document. And the IRS only communicated its failure to find any responsive records two years after CoA Institute submitted its request and filed a lawsuit.

Why the IRS failed to conduct an adequate search for records

Our argument for the inadequacy of the IRS’s search for records reflecting “White House equities” consultations focused on several points, but two were especially important. First, the IRS failed to search its own FOIA office—the most likely custodian of the records and issue. Second, the IRS improperly refused to search for any responsive email correspondence within the Office of Disclosure.

The IRS inexplicably limited its search efforts to the Office of Legislative Affairs, a sub-component of the Office of Chief Counsel, and the Executive Secretariat Correspondence Office, which handles communications with the IRS Commissioner. The agency offered no evidence that it sent search memoranda to its FOIA office, which is part of the “Privacy, Governmental Liaison, and Disclosure” or “PGLD.” In fact, the IRS effectively admitted that it had foregone a search of the Office of Disclosure because a single senior employee testified that he did not believe any responsive records existed. And because “White House equities” review was not mentioned in the Internal Revenue Manual, the FOIA officer assigned to CoA Institute’s request determined that consultations with the White House would never have taken place.

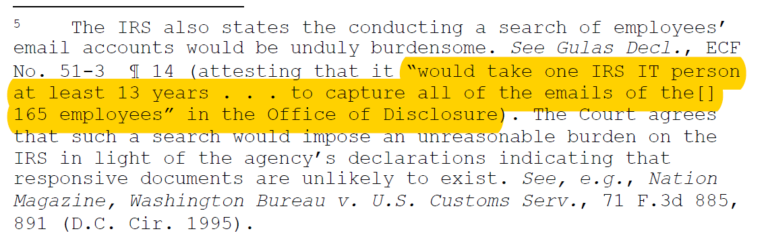

The IRS also refused to search individual email accounts within the Office of Disclosure because it would be too “burdensome.” Remarkably, the IRS claimed it would “take one IRS IT person at least 13 years” to capture the correspondence of all 165 employees within the Office of Disclosure. Yet the IRS offered no explanation for why other reasonable options to search email did not exist, such as requiring individual employees to “self-search” email, conducting a preliminary sample search of individuals within the Office of Disclosure most likely to have responsive records, or making use of e-discovery tools like “Clearwell” and “Encase.”

The Court’s Flawed Opinion and Hyper-Deference to the IRS

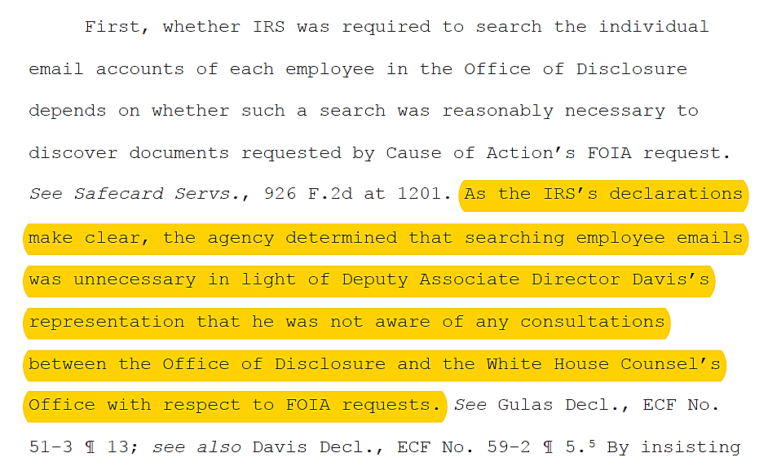

One major flaw in the Court’s decision concerns its uncritical acceptance of a single IRS attorney’s belief about the existence of responsive records within the Office of Disclosure. Although the IRS admittedly conducted a keyword search of its tracking system for incoming FOIA requests, it refused to send out search memoranda or engage in other typical search efforts. The IRS instead relied on the declaration of John Davis, Deputy Associate Director of Disclosure, who claimed that he had never heard of “White House equities” and was unaware of White House consultations ever taking place. On this basis alone, the IRS concluded it was “unreasonable” to conduct a more vigorous search. The Court accepted this reliance without any real explanation when it should have given more consideration to the text of the Craig Memo, which was addressed to the entire Executive Branch—including the IRS—and the fact that the eleven co-defendants in the same case all produced responsive records—nearly all of which were email chains.

As for the search of individual email accounts, the Court yet again uncritically deferred to the IRS’s bizarre claim that it would take thirteen years to process CoA Institute’s FOIA request.

In deferring to the IRS, the Court failed to address the IRS’s practice of conducting email searches by manually inspecting the content of individual hard drives, a central reason why an email search would take so preposterously long. This practice, which requires the IRS to warehouse a lot of old computer equipment, has been repeatedly criticized by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration because it could lead to violations of records management laws.

Additionally, some doubt exists, based on information independently received by CoA Institute from IRS employees, as to the accuracy of the IRS’s claims regarding its ability to conduct an agency- or component-wide search of its email system. Because FOIA cases rarely make it to trial, it is nearly impossible to pin the IRS down on the accuracy of its claims. Regardless, the IRS has certainly made a habit of regularly evading its disclosure obligations, a habit buttressed in this instance by an overly deferential judiciary.

Ryan Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute