Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) has filed an amicus curiae (“friend of the Court”) brief in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in FTC v. AT&T Mobility LLC (“AT&T”) in support of AT&T during the pendency of rehearing en banc of an appeal regarding whether the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC” or “Commission”) has statutory authority to regulate common carriers such as Internet Service Providers (“ISPs”) and telephone companies under Section 5 of the FTC Act.

In September 2016, a unanimous three-judge Panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that because the plain language of the FTC Act categorically exempts common carriers like AT&T from FTC regulation under Section 5, the FTC lacks statutory authority to regulate businesses like AT&T. (Instead, such businesses are regulated by a different federal agency, the Federal Communications Commission (“FCC”) under a different federal statute, the Communications Act.) Consistent with the judicial role and respect for the separation of powers, the Panel explained that “[i]t is not for us to rewrite the statute so that it covers only what we think is necessary to achieve what we think Congress really intended. That is a job for Congress, not the courts.”

The FTC subsequently filed a petition for rehearing en banc supported by a number of “friend of the Court” briefs arguing that the full Ninth Circuit should vacate the Panel decision and rehear the case because, among other things, the Panel decision was inconsistent with their views regarding sound public policy and left a supposed “regulatory gap” that the FTC should be allowed to “fill.” On May 9, 2017, the Ninth Circuit granted the FTC’s petition.

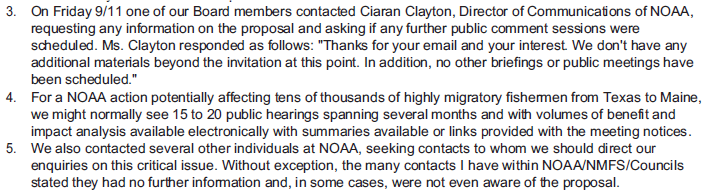

Concerned about this development, our brief argues that the Court should decide the case the same way the Panel did; that is, calling balls and strikes and deciding the case based on the statute’s plain text rather than a federal agency’s subjective views on what it thinks is enlightened public policy for the entire country. Our brief argues that such an approach respects Congress’s legislative role under Article I of the U.S. Constitution, as well as the separation of powers. That is because under the U.S. Constitution only the People’s elected representatives in Congress—not a federal agency like the FTC or FCC and not a federal Court—are allowed to rewrite federal law in response to public policy arguments.

As our brief also notes at pages 3-4: “CoA’s interest in this case also stems from its view that, regardless of whether the FTC’s policy goals are sound, the FTC has now “spun out of the known legal universe and … [is] now orbiting alone in some cold, dark corner of a far-off galaxy, where no one can hear the scream ‘separation of powers.’”

These fitting words, describing FTC’s recent forays in Art. III Courts under Section 5, are not hyperbole, but instead reflect a very disturbing reality. FTC’s self-appointed mantle as perverse executive-agency posse comitatus, a poseur arrogant and lawless unto itself, whose overreach and overregulation do not serve the American people or the public interest.

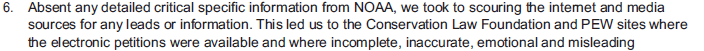

The full brief can be found here.

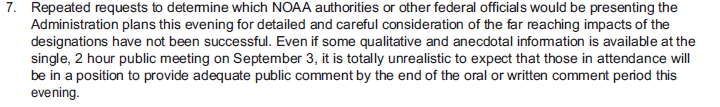

Patrick Massari is assistant vice president at Cause of Action Institute