Corporate welfare undermines the economic liberties of individuals, entrepreneurs and innovators by creating a two-tiered society where the government creates a special set of rules and benefits for favored companies. Recently released documents obtained from a Wisconsin Public Records Request reveal that while many of Foxconn’s tax incentives are tied to employment numbers, the Wisconsin Economic Development Council (WEDC) has no formal process for checking construction employment numbers and has to rely on reports compiled by Foxconn’s construction company. The Foxconn deal in Wisconsin illustrates the dangers of corporate welfare and perfectly sums up why Cause of Action Institute is dedicated to exposing these deals and informing citizens of the risks associated with tax incentives and subsidies designed to benefit a single exclusive company.

How did this all begin? Then Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker promised to bring thousands of blue-collar manufacturing jobs back to state, and in July 2017, Walker signed a deal with Foxconn, one of the largest technology providers in the world. Foxconn promised to invest over $10 billion in Wisconsin and create up to 13,000 jobs by 2022, three-fourths of which would be in manufacturing. As a short-term goal, Foxconn promised to create 5,200 jobs by 2020. In exchange, Walker promised $4.5 billion in subsidies and other benefits. At the time, President Trump touted this extravagant corporate welfare deal as “the eighth wonder of the world,” and supportive Wisconsin legislators declared that it would bring economic prosperity to Wisconsin.

Almost two years later, however, the rosy picture painted by Wisconsin lawmakers has yet to materialize. In late 2018, Nikkei Asian Review wrote that Foxconn was planning on cutting 100,000 jobs worldwide due to global economic uncertainty. Then, Louis Woo, one of Foxconn’s lead negotiators on the deal, announced that they were scrapping plans to build a factory, saying “We can’t compete.” Instead of building a manufacturing facility in Wisconsin, as promised, Foxconn shifted to building research and development facilities expected to employ substantially fewer people from a categorically different labor pool.

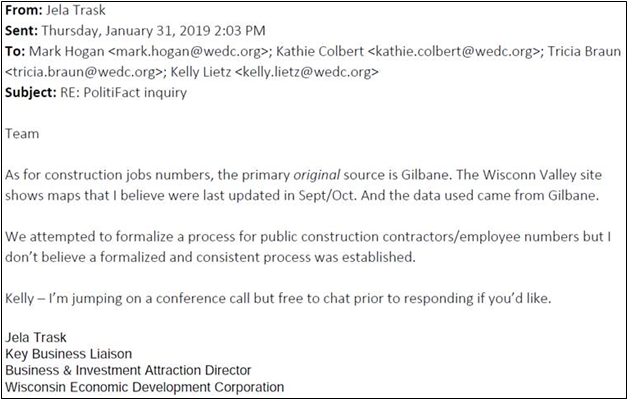

Crucially, much of the subsidies promised to Foxconn are tied to the company meeting agreed-upon employment numbers. However, documents also reveal that WEDC does not have any formal process for verifying Foxconn’s construction job numbers, despite the fact that WEDC’s website claims credit for the project supporting “10,000 construction jobs in each of the next four years.” Instead, it must rely on Foxconn’s construction management company, Gilbane, to report the job numbers to them. WEDC CEO Mark Hogan said in emails that the WEDC “would only have to verify job creation by a sample of job creation data and signed statements from the company.” As if this weren’t bad enough, Wisconsin’s legislature also has no way to determine what jobs Foxconn employees are doing. In a letter to the state legislature’s leadership, several members of Wisconsin’s state senate and house of delegates said “The company has never explained what the 178 employees in Wisconsin are doing now.” For such a huge deal, there is a staggeringly low amount of oversight.

Unless Foxconn hits its hiring targets, it won’t see much of the $4.5 billion subsidy package, but the state and local governments, as well as the nearby communities, have already paid significant costs. In order to secure the necessary land for the Foxconn campus, the village of Mount Pleasant exercised eminent domain to force village residents out of their homes. Mount Pleasant and Racine County have spent over $130 million to prepare for Foxconn construction, and the state of Wisconsin has spent an estimated $120 million on road construction in the nearby area.

When the deal was originally signed, the non-partisan Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau (WFLB) reported that even in the absolute best-case scenario, where all the workers employed by Foxconn live in Wisconsin and all the money spent by Foxconn stays in Wisconsin, the state government would not see any return on its investment until the year 2042. In the same study, WFLB estimates that around 10 percent of people employed by Foxconn in Wisconsin will be filled by Illinois residents, pushing the break-even point back to 2045. In February 2018, Tim Bartik, a senior economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute, told Bloomberg that Wisconsin will never see a return.

Drawing a big company to invest in a particular region can be an exciting proposition for state and local politicians enticed by the prospect of increased employment and economic activity in their state or town. However, when these deals are made final, they often cost more in tax money than they generate. In Wisconsin, the state and local governments proved willing to use every means at their disposal, including the seizure of private property, to try to convince Foxconn to build a multibillion-dollar facility in the state. As the Foxconn deal (and those like it) highlight, state and local governments should not create a separate standard for well-connected companies by granting them billions of dollars in special benefits or using eminent domain to seize private property to advance the needs of a single corporation.

Zeke Rogers is a Research Associate at Cause of Action Institute