Washington, DC – July 19, 2018 – Cause of Action Institute (CoA Institute) today released a report on the failure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to conduct a proper study on its arbitration rule, which banned certain corporations from using pre-dispute arbitration clauses in their consumer credit contracts. CoA Institute Case Study on the CFPB’s Arbitration Rule: How the Bureau Evaded Scientific Guidelines and Bypassed Peer Review—And How to Fix It examines the failings of the arbitration study and offers solutions to ensure future policy is informed by sound science.

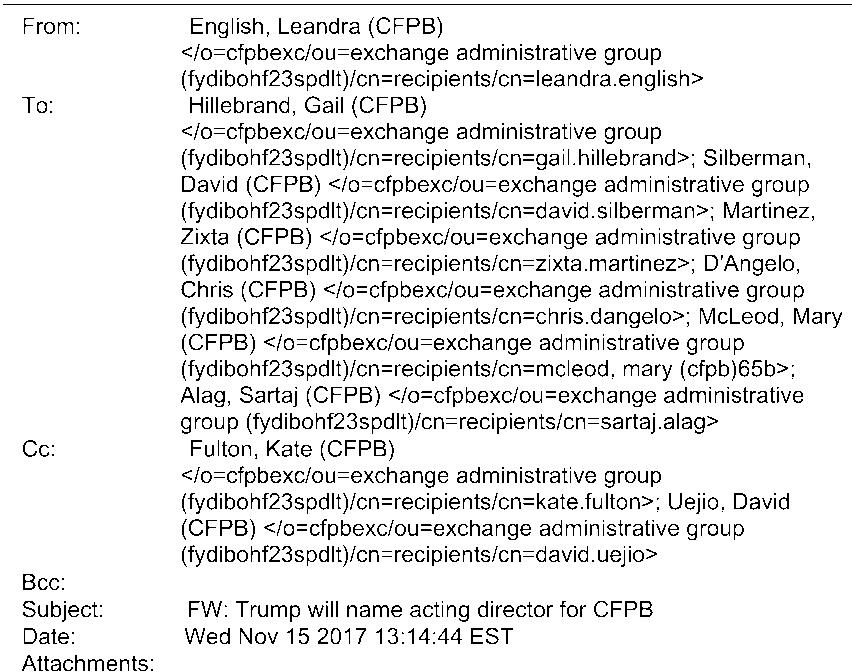

The rule was overturned by Congress and President Trump in February of 2018, but lasting change is needed to CFPB’s analytical approach to prevent future rules from being based on weak science. President Trump nominated Kathy Kraninger as the new potential CFPB director and, just today, July 19, she had her nomination hearing. If confirmed, she needs to immediately take steps to ensure that the CFPB follows the law when conduct future studies and promulgating rules.

CoA Institute attorney Eric R. Bolinder said, “The CFPB not only had to adhere to the orders of Congress in Dodd-Frank to do the study, it was also required to follow the Information Quality Act and Office of Management and Budget guidelines on peer review. The Bureau ignored both. Accountability is needed to keep this too-powerful agency in check.”

As CoA Institute’s report explains:

In the Dodd-Frank Act, Congress delegated to the CFPB the power to study and regulate, if necessary, mandatory-binding arbitration clauses in consumer financial contracts. This power came with an important caveat: the CFPB must first conduct a study on the effect arbitration clauses have on consumers, and any regulation promulgated by the agency must be based on that study. The CFPB already had the goal in mind to regulate and ban these arbitration clauses, driven largely by internal bias and promoted by third-party interests. Instead of conducting an objective study backed by peer-reviewed data, the agency sought a pre-determined result, abusing junk science and methodology to get there.

See the report and more about this issue here.

For any media inquiries, contact media@causeofaction.org.