Shortly after President Trump took office, Politico reported that a small group of career employees at the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”)—“numbering less than a dozen”—were using an encrypted messaging application, called “Signal,” to discuss ways in which to prevent incoming political appointees from implementing the Trump Administration’s policy agenda, which may violate the Federal Records Act. These employees sought to form a sort of “opposition network” to combat any shift in the EPA’s mission and to preserve the “integrity” of “objfedective” scientific data collected for years by the agency.

The use of Signal at the EPA mirrored reports about the use of electronic messaging platforms at other agencies, including the State Department and the Department of Labor. But the EPA seemed to present a particularly potent site for the fermentation of political opposition among the civil service bureaucracy. As reported by Reuters, for example, “[o]ver 400 former EPA staff members” wrote an open letter to the U.S. Senate, asking that former Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt’s nomination as Administrator be rejected, and employees in the EPA’s Chicago regional office held a joint protest against Pruitt with the Sierra Club. Such resistance, as our investigative findings suggested, has yet to dissipate.

* * *

Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) opened its investigation into the use of Signal following Politico’s report. We were concerned that Signal might have been used to conceal internal agency communications from oversight and that the EPA had failed to meet its legal obligations under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) and the Federal Records Act to preserve records of official government business created or obtained on Signal. The EPA’s less-than-sterling reputation for managing electronic records likely inspired the House of Representatives to seek similar clarification from the EPA Inspector General on the Signal scandal.

In our view, to the extent intra-agency Signal correspondence pertained to employees’ plans, in their official capacities, to fight the White House on policy issues, those records were governed by the FOIA and the Federal Records Act, even if created or received on private devices. Applicable guidance from the National Archives and Records Administration (“NARA”) on electronic records states as much. Although some have argued that Signal could have been used in the employees’ personal capacity or “off the record,” such claims rest on “murky legal ground.” At least to the extent employees used Signal on EPA devices, there should have been some mechanism in place to preserve messages until agency authorities could determine whether federal records laws applied. Such a mechanism was particularly important given the difficulty of recovering encrypted messages after deletion.

* * *

To date, CoA Institute’s investigation has unearthed previously undisclosed information about the Signal scandal and the EPA’s efforts to address allegations of legal wrongdoing. In response to our first FOIA lawsuit, the EPA acknowledged that there was an “open law enforcement” investigation and, therefore, many of the records at issue would be withheld in full. The EPA eventually changed its position on this matter and released a number of partially-redacted records. Those records corroborate the alarming facts reported in the media and reveal much more.

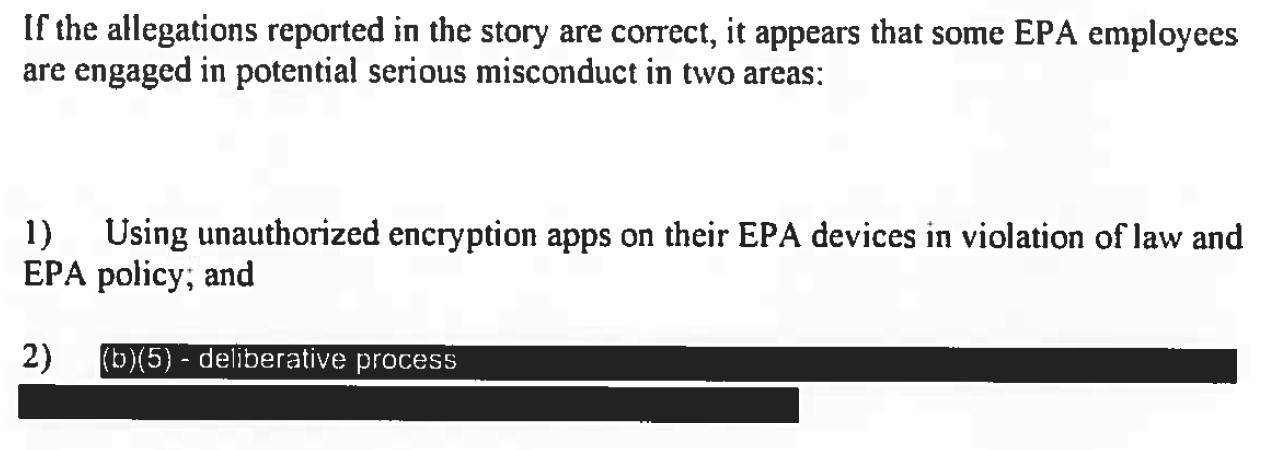

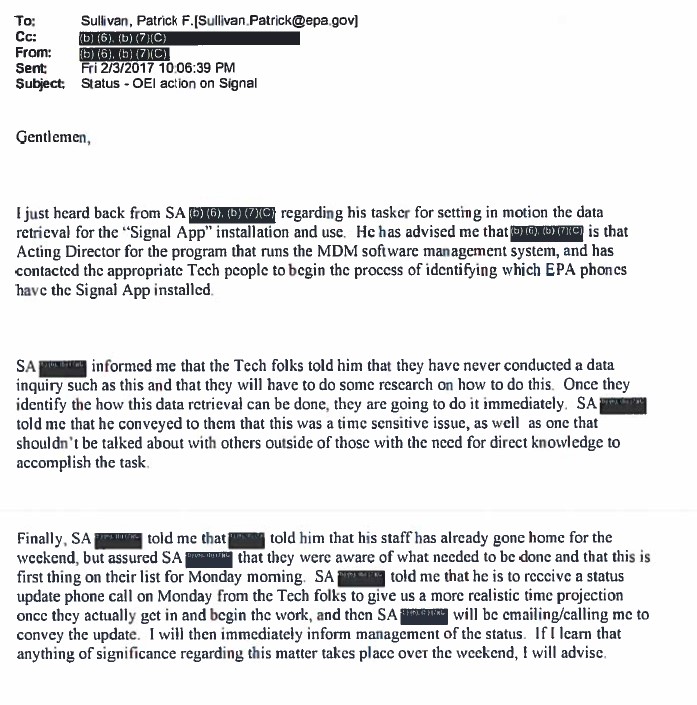

For example, the EPA Office of Inspector General apparently opened its official investigation into the use of Signal only after reading the Washington Times report on CoA Institute’s FOIA efforts. As Assistant Inspector General Patrick Sullivan noted:

Figure 1: February 3, 2017 E-mail from Patrick Sullivan to Arthur Elkins et al.

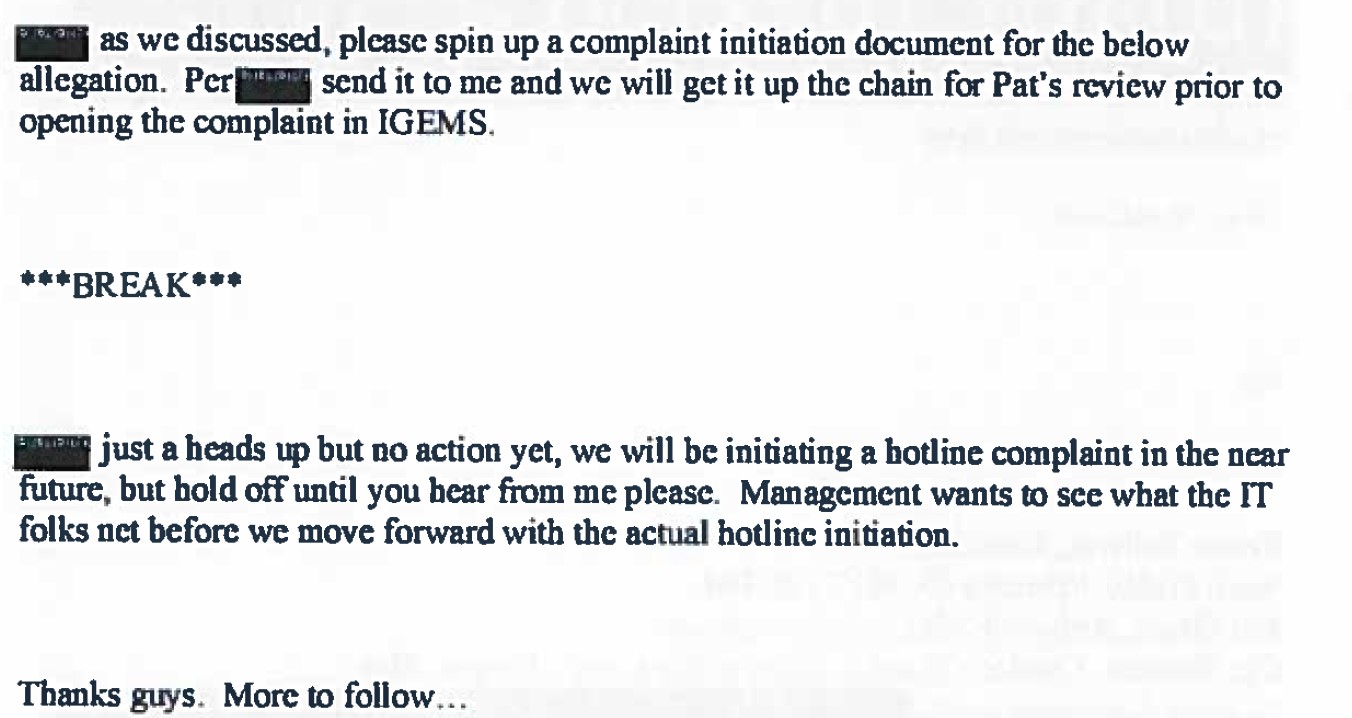

An unidentified special agent then explained how an official “hotline complaint” would be initiated, but only after consulting with IT staff.

Figure 2: February 3, 2017 E-mail from Unidentified Special Agent

The EPA’s administrative offices appear to have been alerted to the Signal scandal before the Inspector General, and only because of the efforts of President Trump’s political appointees. David Schnare almost immediately highlighted the need for a high-level response.

Figure 3: February 2, 2017 E-mail from David Schnare

Mr. Schnare subsequently resigned from the EPA in March 2017, citing difficulties with “antagonistic” career staff opposed to President Trump’s policy agenda.

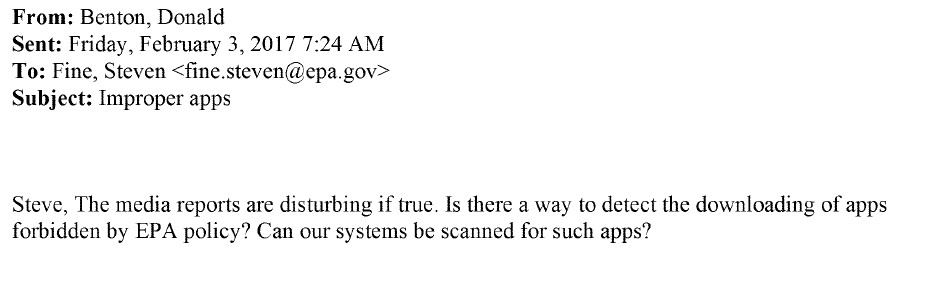

The next day, again in response to the Washington Times, another Trump-appointed advisor, former State Senator Donald Benton, described the media reports as “disturbing if true,” and wondered whether the EPA could detect whether Signal had been improperly downloaded on any devices. (Senator Benton also left the EPA following alleged clashes with Administrator Pruitt.)

Figure 4: February 3, 2017 E-mail from Donald Benton

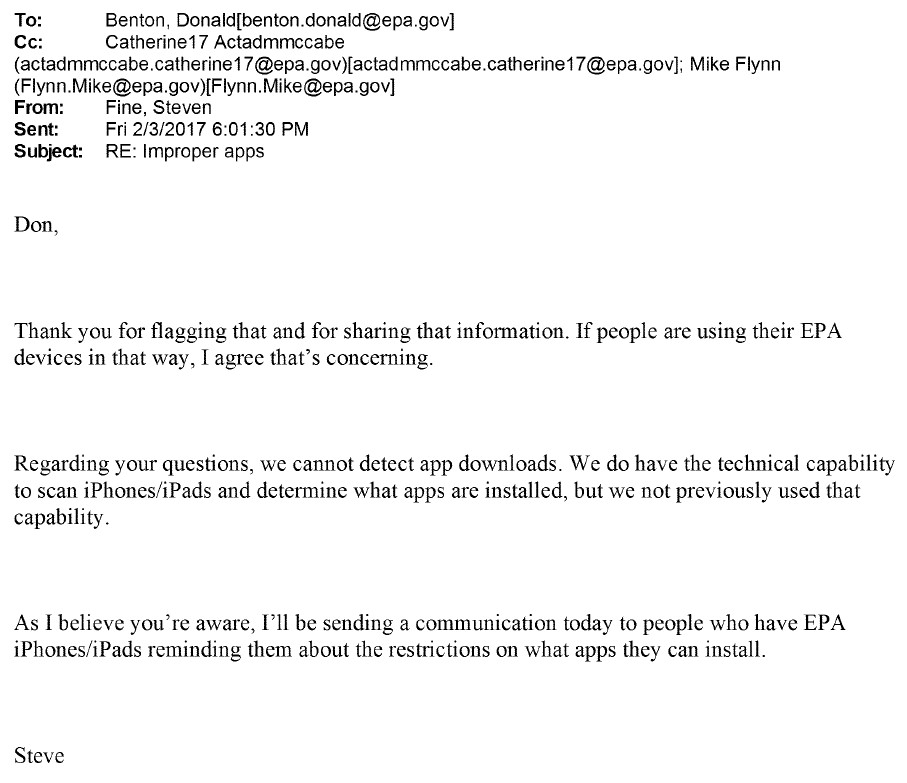

Steven Fine, the EPA’s Acting Assistant Administrator of the Office of Environmental Information and Acting Chief Information Officer, assured Senator Benton that the agency could not detect “app downloads,” but could, in fact, scan devices for already-installed programs.

Figure 5: February 3, 2017 E-mail from Steven Fine

The EPA’s ability to “scan” for the installation of Signal was also revealed during summary judgment briefing against Judicial Watch in unrelated FOIA litigation. A declarant for the EPA described a software tool known as “Mobile Device Management” or “MDM,” which can compile a master report that identifies the applications running on most EPA-furnished equipment. Indeed, Mr. Fine likely wrote to Senator Benton with knowledge of the Inspector General’s pending request for “assistance in identifying whether certain mobile apps, including Signal, had been downloaded” to EPA devices.

Figure 6: February 3, 2017 E-mail from Patrick Sullivan

* * *

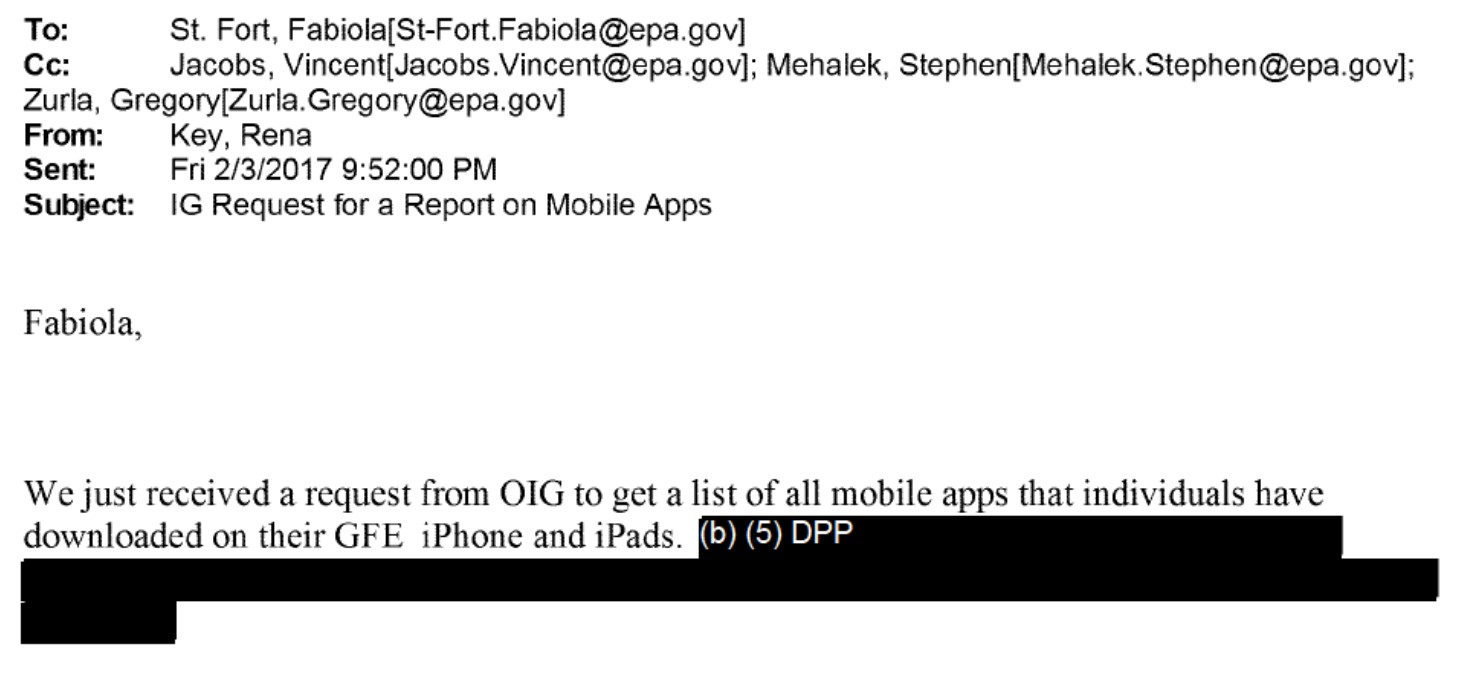

Figure 7: February 3, 2017 E-mail from Rena Key

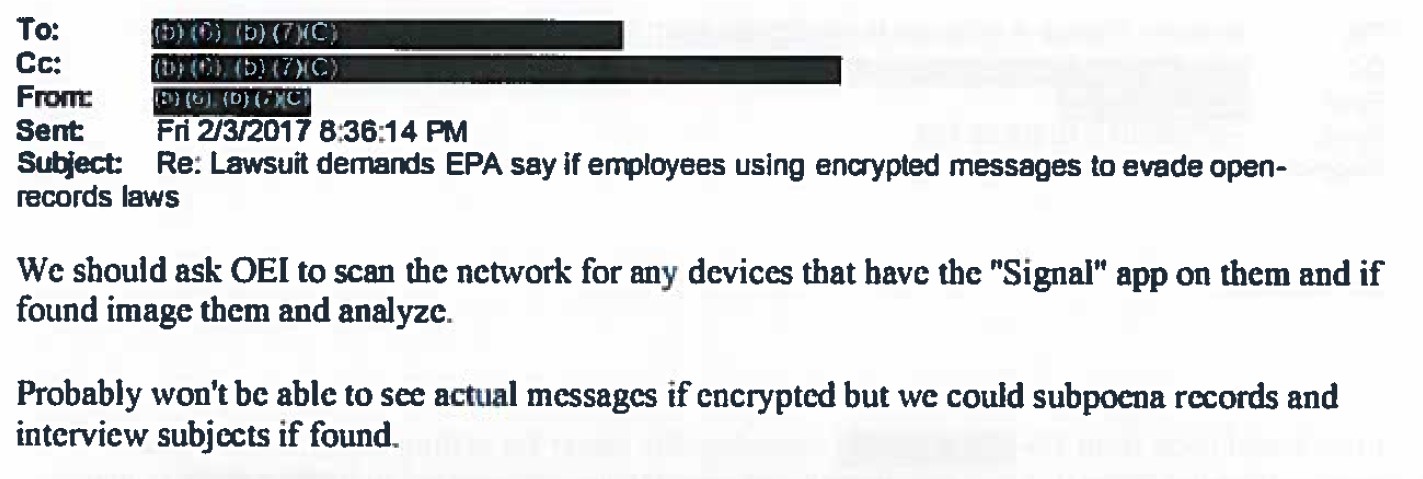

Interestingly, an unidentified special agent in the Office of the Inspector General recognized the limitations in retrieving Signal messages, regardless of the agency’s ability to use MDM to identify the relevant devices on which the application was installed.

Figure 8: February 3, 2017 E-mail from Unidentified Special Agent

An EPA contractor eventually generated the requested report in the MDM devices and transmitted it to the Office of Environmental Information. CoA Institute has a pending FOIA request for a copy of the MDM report.

Records released to CoA Institute also raise or confirm other concerning facts:

- Based on a list of approved “Terms of Service” agreements, EPA employees never were, and still are not, authorized to download and use Signal. Although various social medial tools are approved for use, Signal is not one of them.

- Internal agency guidance leaves individual employees with total discretion in determining whether text or instant messages need to be forwarded to an official e-mail address and agency recordkeeping system. Although the guidance highlights the differences between “substantive (or non-transitory)” records and those that need not be retained, there is no clear system of oversight to prevent the unauthorized deletion of electronic records.

- On February 22, 2017, NARA wrote to the EPA to request an update on the records management issues involved in the Signal scandal. The EPA responded a month later, explaining that its investigation was still ongoing and a final report would be forthcoming. The agency referred to its existing list of approved “Terms of Service” agreements, as well as its efforts to remind employees of their individual responsibility to preserve certain records. No specific mention was made of the use of Signal.

As additional information becomes available, we will provide further analysis on the EPA’s investigation into the unauthorized use of Signal.

Selected records from CoA Institute’s FOIA production, excepts of which have been used above, can be accessed here.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.