Judge James Boasberg of the U.S District Court for the District of Columbia ruled this week that the Export-Import Bank (“EXIM Bank”) must produce a variety of records it initially withheld in response to two FOIA requests from Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”). CoA Institute’s September 20, 2018 FOIA request sought all communications to or from EXIM leadership regarding key EXIM stakeholders and beneficiaries. The May 2019 FOIA request sought information after a Government Accountability Office (“GAO”) report found EXIM potentially provided billions in financing to companies with delinquent federal debt by failing to use a readily available federal database. Learn More

GAO Report Finds EXIM Potentially Provides Billions in Financing to Companies with Delinquent Federal Debt

While the Export-Import Bank (EXIM) celebrated the recent confirmation of its president and two members of its board of directors, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a troubling report concerning EXIM potentially providing billions of dollars in loans and financing to companies improperly. GAO found EXIM failed to use a federal database available to all government agencies free of charge to identify companies that have delinquent federal debt. Consequently, EXIM may have provided financing to ineligible companies and increased it’s susceptibility to fraud.

GAO Finds Ex-Im Bank Lacks Comprehensive Fraud Prevention: CoA Renews Push to Abolish

The Export-Import Bank of the United States (“Ex-Im Bank” or “Bank”) is a federal agency that provides financial credit to those who claim they are unable to obtain it privately. In reality, Ex-Im Bank offers taxpayer-guaranteed loans to politically-connected companies while leaving smaller companies at a competitive disadvantage. Last August, citing Ex-Im Bank as a form of corporate welfare, Cause of Action Institute advocated for its abolishment.

Now, a new Government Accountability Office (GAO) report finds that Ex-Im Bank lacks a comprehensive framework to deter fraud, needs comprehensive fraud risk management reform, and currently poses a significant risk of loss to taxpayers by failing to provide these adequate protections against fraud and abuse.

Between October 2016 to July 2018, the GAO conducted a performance audit of the Bank, surveying more than 400 employees about the organization’s fraud risk management capabilities. The GAO report concluded that:

“[T]he Bank has approached fraud risk management on a fragmented, reactive basis, and its anti-fraud activities have not been marshalled into the kind of comprehensive, strategic fraud risk management regime envisioned by GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework and its leading practices.”

The report found that employees were concerned about the lack of proactive measures being taken to combat and prevent fraud. The protocols in place focus on reacting after the fraud was committed, rather than preventing fraud from occurring. The GAO noted that the Bank was making efforts to reform its anti-fraud capabilities, but it was not clear whether improvements were keeping pace with expectations.

The GAO report surveyed employees and included the following comments and summaries about the Bank’s attitude towards addressing fraud:

- “The Bank is more concerned with increasing sales than preventing fraud.”

- “[The current division of responsibilities] is not the most effective way for the Bank to oversee fraud and fraud risk, as responsibility needs to be given to the teams on the front end—such as the individual relationship managers and loan officers—not on the back end.”

- “[The current arrangement]seems to be more of an after-the-fact approach to potentially (if reluctantly) detecting fraud than any proactive encouragement to actively prevent fraud.”

These comments from Ex-Im Bank employees illustrate both a cultural challenge within the Bank and the Bank’s failure in constructing comprehensive reforms to prevent fraud. The GAO presented Ex-Im Bank with a list of recommendations to address its vulnerabilities and create a culture of prevention rather than reaction.

Given the Bank operates with taxpayer funds, these improvements are critical. In the words of a concerned Bank employee, “More due diligence should be required in order to qualify for the U.S. government’s support.”

It is Cause of Action’s mission to advocate for a transparent and accountable government free from fraud and cronyism. The Ex-Im Bank is a key example where oversight and accountability are critical to ensuring its service to the public interest. For too long, the Ex-Im Bank has been linked to providing political favors for well-connected corporations and undermining fair market competition, and Cause of Action Institute will continue to advocate for ending the Bank and this form of corporate welfare.

Ethan Yang is a Research Fellow at Cause of Action Institute.

GAO Report Highlights Agencies Failing to Implement the FOIA

A report released yesterday by the Government Accountability Office (“GAO”) provides alarming details about the dearth of agency efforts to fully implement the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”). GAO previewed a draft of its report in March 2018 when its Director of Information Technology Management Issues, David Powner, testified at a hearing on FOIA compliance before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary. At the time, GAO published a concurrent report on how federal courts regularly fail to refer cases to the Office of Special Counsel (“OSC”) to determine whether disciplinary action is warranted in instances where officials have acted arbitrarily or capriciously in withholding records. (Cause of Action Institute’s (“CoA Institute”) commentary on that issue can be found here.) Yesterday’s report finalizes GAO’s findings and incorporates feedback from the eighteen agencies in the sample subject to the audit.

Many Agencies Have Failed to Update Regulations and Appoint Chief FOIA Officers

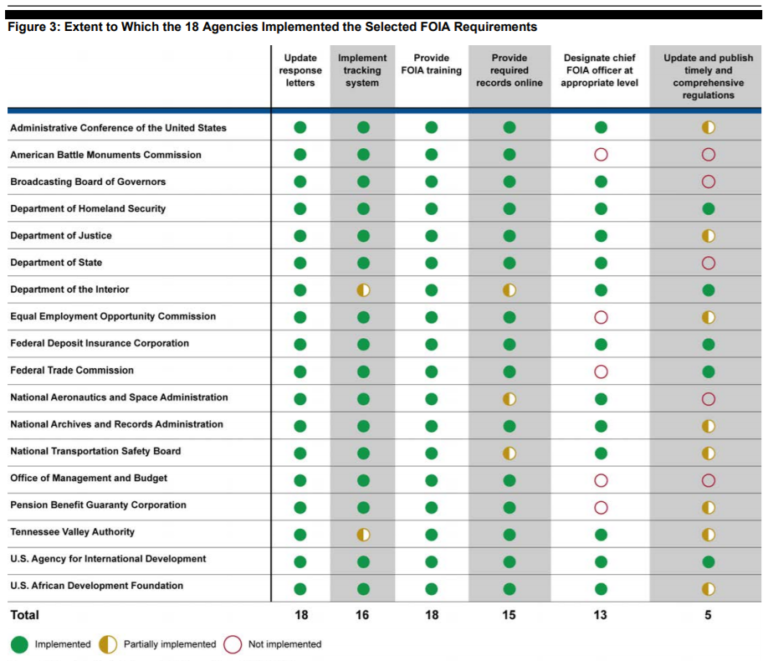

One aspect of GAO’s audit involved reviewing whether the eighteen agencies properly implemented various requirements introduced by the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016 and the OPEN Government Act of 2007. Those amendments to the FOIA require agencies, inter alia, to designate chief FOIA officers, publish timely and comprehensive regulations, and update response letters to indicate things such as an extended, 90-day appeal period. GAO also evaluated what efforts were underway by the Office of Management and Budget and the Office of Information Policy to develop a government-wide FOIA portal.

The chart above, which is taken from the GAO report, encapsulates some of the unfortunate findings. Even though it is a statutory requirement, five of the eighteen agencies have not designated a chief FOIA officer in line with applicable requirements (e.g., appointing a senior official at the Assistant Secretary or equivalent level). Chief FOIA officers are responsible for monitoring agency-wide compliance with the FOIA, making recommendations for improving FOIA processing, assessing the need for regulatory revisions each year, and serving as a liaison with the Department of Justice Office of Information Policy, the Office of Government Information Services, and the Chief FOIA Officers Council. It remains unclear why some agencies are reticent to comply with this aspect of the FOIA.

Another disturbing finding is that few agencies in the sample timely updated and published regulations to implement the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016. At least five agencies have deficient regulations—such as the Department of State—or have not bothered to issue a preliminary rulemaking—such as the White House Office of Management and Budget (“OMB”). Agencies offered several reasons for why they have not complied with the law, with most citing a lengthy internal review process. The State Department explained that it had just finished updating its regulations before passage of the FOIA Improvement Act. The U.S. African Development Foundation, however, claimed that it did not even need “to disclose information regarding fees in their regulation” because it “has not charged a fee for unusual circumstances.”

OMB’s failure to satisfy GAO’s criteria for proper FOIA regulations is unsurprising and indicative of a general disregard for regulatory compliance with the FOIA at the agency. For example, for the past few years, CoA Institute has carefully tracked whether agency FOIA regulations have been updated to include the current statutory definition of a “representative of the news media.” Prior to the D.C. Circuit’s landmark 2015 decision in Cause of Action v. Federal Trade Commission, many agencies relied on OMB’s Uniform Freedom of Information Fee Schedule and Guidelines to impose an “organized and operated” standard that deprived nascent media groups of preferential fee treatment. The OMB Guidelines, which were written in 1987, have never been updated, despite requests from the FOIA Advisory Committee and the Archivist of the United States. CoA Institute thus filed its own petition for rulemaking on the issue in June 2016, followed by a lawsuit last November after OMB failed to respond.

Agencies Have Made Little Progress on FOIA Backlogs

Another aspect of GAO’s audit involved examining whether the eighteen agencies had made any headway in reducing their FOIA request backlog, as well as cataloging the statutes used in conjunction with Exemption 3 to withhold records from the public. GAO found that few agencies had managed to reduce their outstanding backlog. One major reason for the lack of progress on reducing backlogs was the failure of most agencies to implement “comprehensive plans” laying any sort of strategy. As for GAO’s catalogue of statues used to withhold information exempt as a matter of law, the most commonly cited provisions were 8 U.S.C. § 1202(f), which concerns records about the issuance or refusal of a visa, and 26 U.S.C. § 6103, which protects the confidentiality of tax returns and return information.

GAO’s audit is an important indication of how far many agencies must go to comply fully with the FOIA. This is particularly true insofar as GAO’s findings can be generalized across the entire administrative state. Congress, the transparency community, and the American public must exert even greater pressure on Executive Branch agencies to meet their obligations under the law and to improve their commitment to open government.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute

GAO audit of Office of Special Counsel referrals under FOIA reveals weakness in the statute

An audit report released yesterday by the Government Accountability Office (“GAO”) provides alarming details concerning the lack of referral of cases of wrongful withholding under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) to the Office of Special Counsel (“OSC”). Since at least 2008, neither the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) nor any federal court has referred a single case to the OSC so that the agency could investigate whether disciplinary action would be warranted for the arbitrary or capricious withholding of records litigated in court. The publication of the audit coincided with the testimony of the GAO’s Director of Information Technology Management Issues, David Powner, at a hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

OSC’s Investigatory Role under the FOIA

Congress envisaged a special role for the OSC in policing agency behavior with respect to the withholding of records. Section 552(b)(4)(F) of the FOIA obliges the OSC to investigate whether disciplinary action is warranted against an official responsible for withholding records if a federal court has (1) ordered the production of those records, (2) assessed reasonable attorney fees and litigation costs against the government, and (3) issued a “written finding” that the case “raises questions whether agency personnel acted arbitrarily and capriciously with respect to the withholding.”

Once these conditions are met in any given case, the Attorney General must refer the matter for investigation to the OSC, and the agency at issue must take any corrective action recommended by the OSC. If the government fails to comply, a court can punish a responsible official with contempt. Apart from the FOIA, the OSC also has independent authority under 5 U.S.C. § 1216(a)(3) to investigate most allegations of arbitrary or capricious withholding of records.

No Referrals Have Been Made to the OSC Over the Past Ten Years

After examining various records and interviewing officials at the DOJ and OSC, the GAO concluded that, since 2008, no court orders have issued in a FOIA lawsuit such that referral to the OSC was appropriate. At the same time, between 2013 and 2016, requesters in at least six cases nevertheless sought a court-ordered referral to the OSC. In all six cases, the court denied the requests.

The referral provisions of the FOIA are toothless in practice. According to one source, the OSC has investigated only two possible cases of punishable wrongdoing. In Holly v. Acree, the OSC concluded that it could not determine the “officer or employee who was primarily responsible for the [wrongful] withholding.” And in Long v. Internal Revenue Service, the OSC closed its investigation without any public findings. Furthermore, despite numerous allegations and some instances of field investigation over the years, it does not appear that the OSC has ever initiated a disciplinary proceeding under Section 1216(a)(3).

Judicial decisions likewise exemplify the reticence of courts to refer cases to the OSC. The judicial branch is already highly deferential to the government when assessing justifications for the treatment of FOIA records. That deference appears to affect the analysis of whether it is appropriate to issue a “written finding” that an official or employee may have personally acted wrongfully. For example, in the case of Kempker-Cloyd v. Department of Justice, No. 97-253, 1999 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 4813 (W.D. Mich. 1999), the court acknowledged that an agency failed to act in a timely manner, to conduct adequate searches, or to comply with the FOIA “in good faith.” On further order, the court also determined the agency was liable for attorney fees and litigation costs. Yet the court still did not believe there was evidence suggesting the agency acted in an arbitrary or capricious manner. In a more recent case, Consumer Federation of America v. Department of Agriculture, 539 F. Supp. 2d 225 (D.D.C. 2008), when faced with a motion to refer the case to the OSC after the agency conducted an inadequate search and lost responsive records, the court sidestepped the issue altogether by ordering the agency to file a supplemental declaration confirming its promise—made during oral argument—to revise the process for handling requests for electronic records and to correct the problems that led to the loss of the records at issue. Countless other examples of judicial refusal to engage with the OSC referral provisions abound.

The FOIA Should Be Strengthened to Hold Agency Officials Responsible for Wrongful Withholdings

As it stands, agency officials are effectively unaccountable for their decision-making under the FOIA. There is no punishment for an agency when it mishandles a request or forces a requester to file a lawsuit to obtain records or fight wrongful withholdings. Indeed, it is the taxpayer who ends up footing the bill for the government’s litigation costs. The individuals responsible for processing requests, therefore, have little incentive aside from their personal commitment to transparency to ensure that agency decision-making is consistent with the law. Even if a requester prevails in court, he faces the uphill battle of securing attorney fees and recoverable litigation costs, not to mention the tremendous difficulty of obtaining a written finding of arbitrary and capricious behavior on the part of the agency.

The requester community deserves better. If agency officials knew that they would be held personally responsible for their administration of the FOIA, we would have a more efficient disclosure regime and a more transparent government. The OSC can and should play an important role here, but the FOIA, as implemented, does not currently facilitate that endeavor. Congress should undertake efforts to remedy the situation.

Ryan Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute

GAO on CPPW: Nothing to See Here

Arriving in the context of a broader lobbying controversy, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) recently released a report on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) lobbying policies. Even by the standards of government investigators, the GAO did a pathetic job examining the degree of CDC oversight of the Communities Putting Prevention to Work (CPPW) program and its award recipients. It makes more sense to describe GAO’s work as a survey of CDC employees, rather than as an independent evaluative report.

In responding to requests for information from Senators Lamar Alexander (R-TN), Tom Coburn (R-OK), Susan Collins (R-ME), and Orrin Hatch (R-UT), the GAO reviewed:

[D]ocuments provided by CDC, including the written policy on lobbying that pertained to CPPW award recipients; CPPW award notices, which were the written agreements between the CDC and recipients; documentation generated by CDC staff during the monitoring of CPPW recipients; and CDC site visit reports.

The GAO also interviewed CDC officials regarding the lobbying policy that applied to CPPW award recipients in two hundred eighty CPPW cooperative agreements, all of which were made in fiscal year 2010.

But just over six weeks ago, Cause of Action (CoA) released its own report, “CPPW: Putting Politics to Work,” examining twelve grant recipients based on responses to FOIA requests we sent to the CDC. Of those twelve, eight appeared to use federal funds to illegally lobby for things like tobacco taxes, clean air ordinances, and bans on sugary-sweetened drinks, rather than on sensible preventative health efforts.

CoA’s report also demonstrated that the CDC failed to take comprehensive action in one case of illegal lobbying it actually managed to identify. While the GAO had access to information on all grant recipients and considered two potential lobbying violations identified by the CDC, CoA continues to await more information from the CDC on the other grant recipients. If we found that eight of the twelve we have been able to investigate up to this point are at risk of violating federal law, how many more instances are out there that the GAO and CDC have failed to uncover?

Unfortunately, the GAO’s report was not a substantive investigation. In fact, the most noteworthy aspect of the GAO report is how sparingly the GAO examined the CDC’s ability to follow-through on its own processes for correcting instances of illegal lobbying by grantees. Instead, the GAO confirmed that the CDC engaged in no active audit function for the CPPW program, could not independently verify subrecipient expenses, and depended on self-reporting by grantees.

These findings are particularly troubling because, as the GAO fails to mention in its report, by 2015 the Department of Health and Human Services will be able to spend $2 billion per year in perpetuity on similar programs through the Affordable Care Act’s Prevention and Public Health Fund.