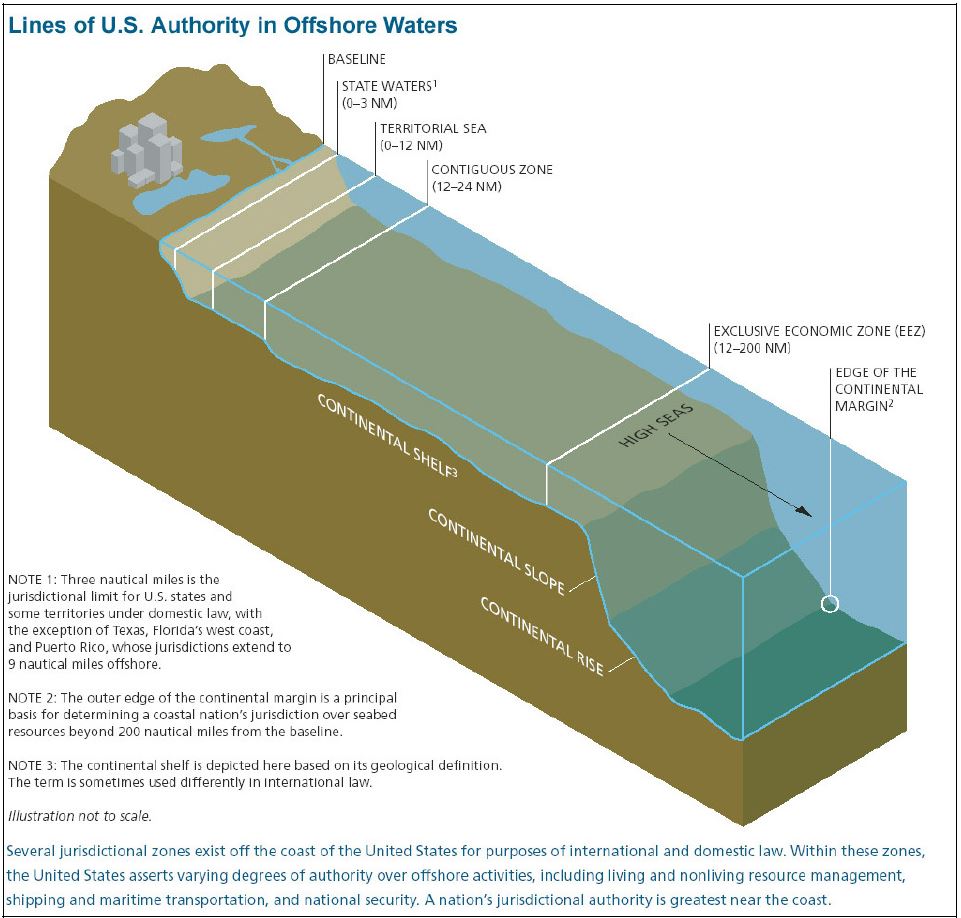

Yesterday we provided a synopsis of certain statutory and regulatory schemes that govern America’s coastal and internal waters and reviewed the definitions of the jurisdictional zones that apply to United States’ waters. Today we continue our discussion of how the various schemes apply in the jurisdictional zones.

SOURCE: U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy, 2004.

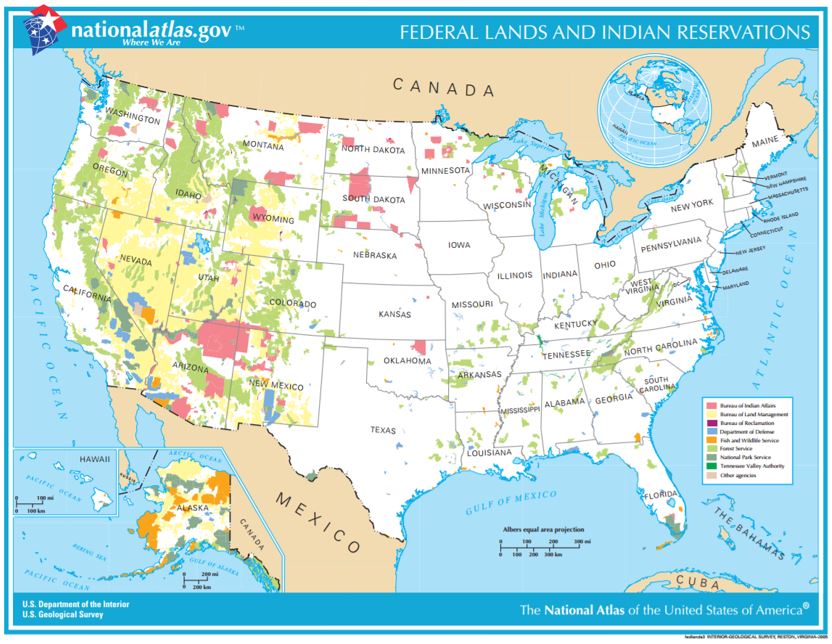

A full description of all programs that touch on the jurisdictional waters of the United States and the activities that take place thereon is beyond the scope of this analysis. However, the following programs should inform—and in some cases are legally necessary to—any change in status relating to United States’ coastal and internal waters.

Land and Water Management Laws

The Coastal Zone Management Act (“CZMA”) was enacted to “preserve, protect, develop, and where possible, to restore or enhance, the resources of the nation’s coastal zone for this and succeeding generations;” with the purpose, “to encourage and assist the states to exercise effectively their responsibilities in the coastal zone through the development and implementation of management programs to achieve wise use of the land and water resources of the coastal zone, giving full consideration to ecological, cultural, historic, and esthetic values as well as the needs for compatible economic development.”

The CZMA is administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (“NOAA”) and thus falls under the jurisdiction of the Department of Commerce. Under the CZMA, states are incentivized to develop coastal management programs with the assurance that, with some exceptions, federal actions will be constrained to those that are consistent with state-developed and federally-approved coastal management programs (the “federal consistency” provision). More information about the CZMA may be found on NOAA’s website, and individual state coastal management programs may be accessed here. State coastal management programs can be quite extensive, addressing such diverse issues as seafloor and habitat mapping, flooding and erosion, lake access, education, beach management, seismic mapping, and protecting natural habitats and wildlife.

With the exception of Alaska, all 35 coastal and Great Lakes states and territories participate in the National Coastal Zone Management Program.

The Clean Water Act (“CWA”) was enacted to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s Waters.” The goals of the CWA were to make all waters safe for fish and people, and to eliminate the discharge of pollutants into the waters of the United States.[1] Amendments to the Act provide for estuary management and protection, with special programs authorized for the Chesapeake Bay, the Great Lakes, and Long Island Sound. The CWA is administered primarily by the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”), which has established a similar program for the Gulf of Mexico.[2] States that have a federally-approved coastal management program must develop and submit a coastal nonpoint[3] pollution control plan to NOAA and the EPA for approval, identifying land uses that contribute to coastal water quality degradation and critical coastal areas.[4]

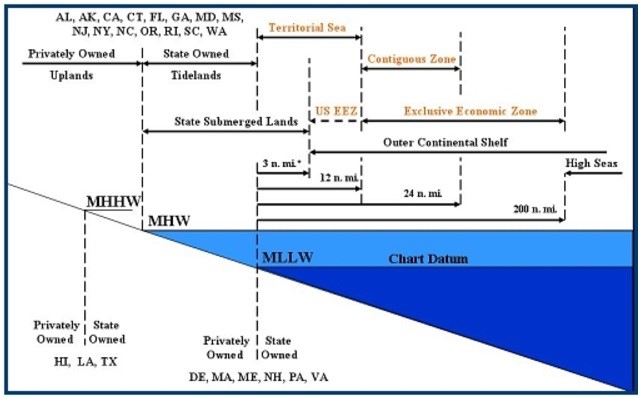

The Submerged Lands Act (“SLA”) established in the states: “(1) title to and ownership of the lands beneath navigable waters within the boundaries of the respective States, and the natural resources within such lands and waters, and (2) the right and power to manage, administer, lease, develop, and use the said lands and natural resources all in accordance with applicable State law be, and they are, subject to the provisions hereof, recognized, confirmed, established, and vested in and assigned to the respective States.”[5] Natural resources, for purposes of the SLA, include oil, gas, and other minerals; and fish, shellfish, sponges, kelp, and other marine life; but do not include the use of water for the production of power.[6]

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (“OCSLA”) established federal jurisdiction over the submerged lands “lying seaward and outside of” lands subject to the Submerged Lands Act extending “of which the subsoil and seabed appertain to the United States and are subject to its jurisdiction and control.” The Act purported to extend limited-purpose constitutional and political jurisdiction over the area:

The Constitution and laws and civil and political jurisdiction of the United States are extended to the subsoil and seabed of the outer Continental Shelf and to all artificial islands, and all installations and other devices permanently or temporarily attached to the seabed, which may be erected thereon for the purpose of exploring for, developing, or producing resources therefrom, or any such installation or other device (other than a ship or vessel) for the purpose of transporting such resources, to the same extent as if the outer Continental Shelf were an area of exclusive Federal jurisdiction located within a State: Provided, however, That mineral leases on the outer Continental Shelf shall be maintained or issued only under the provisions of this subchapter.[7]

Under the Act, the Secretary of the Interior is authorized to develop oil, gas, and other mineral deposits via permitting and leasing; and is also charged with suspending or prohibiting such activity “if there is a threat of serious, irreparable, or immediate harm or damage to life (including fish and other aquatic life), to property, to any mineral deposits (in areas leased or not leased), or to the marine, coastal, or human environment.” Activity under this Act must be coordinated with the CZMA and requires the Secretary to coordinate with other agencies and the affected states.[8]

Fishery and Species Management Laws

In 1976, the Fishery Conversation and Management Act, now the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (“Magnuson-Stevens Act”), extended exclusive U.S. fishery jurisdiction to 200 miles offshore, covering the area that later became the EEZ.[9] The Magnuson-Stevens Act established eight regional fishery management councils.

The Regional Councils are composed of members representing commercial and recreational fishing, environmental, and academic interests, as well as state and federal government. Regional Councils are required to:

- Develop and amend Fishery Management Plans

- Convene committees and advisory panels and conduct public meetings

- Develop research priorities in conjunction with a Scientific and Statistical Committee

- Select fishery management options

- Set annual catch limits based on best available science

- Develop and implement rebuilding plans

The Magnuson-Stevens Act has been amended by the Sustainable Fisheries Act of 1996 and the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Reauthorization Act of 2006, which were intended to strengthen sustainable fish stock requirements; promote market-based management strategies, such as catch shares; strengthen the role of science through peer review; and enhance international fisheries sustainability. Catch shares are exclusive allocations of fishing rights that are provided by the fishery management council and are transferable in accordance with the policy and criteria established by the controlling fishery management council.

Once a Fishery Management Plan has been written to include the ten national standards and research about the fishery, it must be submitted to the Secretary of Commerce for approval.[10] The Secretary also has independent authority to prepare a Fishery Management Plan for a region.[11]

The focus of the Magnuson-Stevens Act is on maintaining sustainable fisheries. Accordingly, the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Act is administered by the National Marine Fisheries Service within the Department of Commerce. Additional information on the Magnuson-Stevens Act may be found here.

The Marine Mammal Protection Act (“MMPA”) differs from the Magnuson-Stevens Act in that it focuses on the health of marine mammal populations rather than on fishing yield. Subject to a few exceptions, the MMPA places a moratorium on the taking and importation of marine mammals and marine mammal products.[12] The MMPA is administered by two agencies—the National Marine Fisheries Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service within the Department of the Interior. The MMPA does not impose management responsibility on states or localities; however, a state may enter into a cooperative agreement for delegation of the administration and enforcement of the MMPA.[13]

The Endangered Species Act (“ESA”) also focuses on conservation of species and, like the MMPA, is administered by the National Marine Fisheries Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[14] The ESA does not mandate any permanent management structure that involves the states. However, Section 6 of the ESA does provide a mechanism for cooperation between the Fisheries Service and States in which the Fisheries Service is authorized to enter into agreements with any state that establishes and maintains an “adequate and active” program for the conservation of endangered and threatened species. Once a State enters into such an agreement, the Fisheries Service is authorized to assist in, and provide Federal funding for, implementation of the State’s conservation program.

The National Marine Fisheries Service also has obligations under the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act and National Environmental Policy Act to consult, coordinate, and implement regulations regarding essential fish habitat with other federal agencies.[15]

These statutory frameworks are intended to work together in managing and protecting the coastal waters of the United States, in light of the interests of the coastal states, the preservation of marine life, natural resource development, and the interests of stakeholders such as fishermen, scientists, visitors, and foreign entities engaged in traditional uses of the seas (such as the right of safe passage). To achieve that purpose, coordination and accommodation is necessary to develop the comprehensive management plans required by, for example, the Coastal Zone Management Act and the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act. Notably, this extensive coordination and balancing of local, federal, and international interests does not contemplate, and can be disrupted by, the sudden withdrawal of territory from the statutory schemes under the Antiquities Act; nor do these Acts include specific provisions for addressing lost rights; displaced scientific, commercial, or environmental planning; or conflict arising from a sudden change in jurisdiction between agencies.

Our series will continue next week with an update on the status of President Trump’s April 26 Antiquities Act Executive Order.

Any questions, commentary, or criticisms? Please e-mail us at kara.mckenna@causeofaction.org and/or cynthia.crawford@causeofaction.org

Cynthia F. Crawford is a Senior Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.

Kara E. McKenna is a Counsel at Cause of Action Institute. You can follow her on Twitter @Kara_McK

[3] Nonpoint pollution refers to runoff from rain or snow that picks up and carries away natural and human-made pollutants into coastal and internal waters

[15] Review of U.S. Ocean and Coastal Law, Appendix 6, U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy, 2004, at 46.