Over the past year, Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) has been investigating the Department of Veterans Affairs for its continued politicization (here, here, and here) of the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”). That politicization takes the form of “sensitive review,” which refers generally to the practice of giving certain FOIA requests extra scrutiny. Sensitive review usually entails an additional layer of review or “consultation” with interested parties before potentially embarrassing or politically sensitive records are released to the public. At its best, it almost always causes delay. At its worst, it leads to intentionally inadequate searches, politicized document review, improper redaction, and incomplete disclosure.

The earliest sensitive review procedures that we’ve discovered at the VA date to the closing years of the Bush Administration. In August 2007, the VA issued a directive that identified guidance for the processing of so-called “high visibility” requests. CoA Institute recently acquired a copy of that August 2007 guidance, which it is now publishing for the first time. In the guidance, the VA defines “high visibility” requests to include anything implicating records about “controversial issues,” or which may have been submitted by “members of Congress,” the “media,” or “individuals . . . in connection with pending or future litigation.”

Once a “high visibility” request was identified, VA FOIA officers were prohibited from taking any further substantive action until all agency “stakeholders” were notified, had communicated with each other, and then “determined the best course of action for processing the request.” Certain administrative decisions were categorically reserved to higher-level FOIA officials, such as the director of the VA Records Management Service.

Once a “high visibility” request was identified, VA FOIA officers were prohibited from taking any further substantive action until all agency “stakeholders” were notified, had communicated with each other, and then “determined the best course of action for processing the request.” Certain administrative decisions were categorically reserved to higher-level FOIA officials, such as the director of the VA Records Management Service.

Subsequent iterations of the VA’s sensitive review guidance retained the same approach for potentially controversial or newsworthy requests. An October 2013 memorandum, for example, instructed agency components and program teams to clear FOIA responses and productions through centralized departmental FOIA offices. More alarmingly, a February 2014 memorandum reiterated the need for “consultation” with political leadership on requests of “substantial interest”—an ambiguous term that the agency failed to define at the time. Records obtained by CoA Institute, however, shed some more light on the meaning of “substantial interest” and how sensitive review continued to develop at the VA.

In May 2014, shortly after the issuance of the February memorandum, the VA distributed further guidance that defined a “Substantial Interest FOIA Request” to include, among other things, any request related to (1) threats to public health; (2) high profile local or national incidents involving the VA; or (3) allegations of waste, fraud, or abuse. Once a request of “substantial interest” was identified, no action would be taken by a program or field office without higher-level approval.

Following a trend that CoA Institute has identified at other agencies, the VA also started to require its FOIA officers to “flag” requests from the news media or members of Congress, regardless of whether they otherwise qualified as “substantial interest” requests. Although the VA described this practice as a form of “notification,” the agency’s guidance explicitly prohibited any FOIA response from issuing until “senior leadership” had been apprised of the proposed determination and only after departmental FOIA officials had signed-off. This “notification process”—which, in practice, may have involved political meddling in FOIA administration—remained substantively unchanged when it was reauthorized in August 2015 and, yet again, in August 2016.

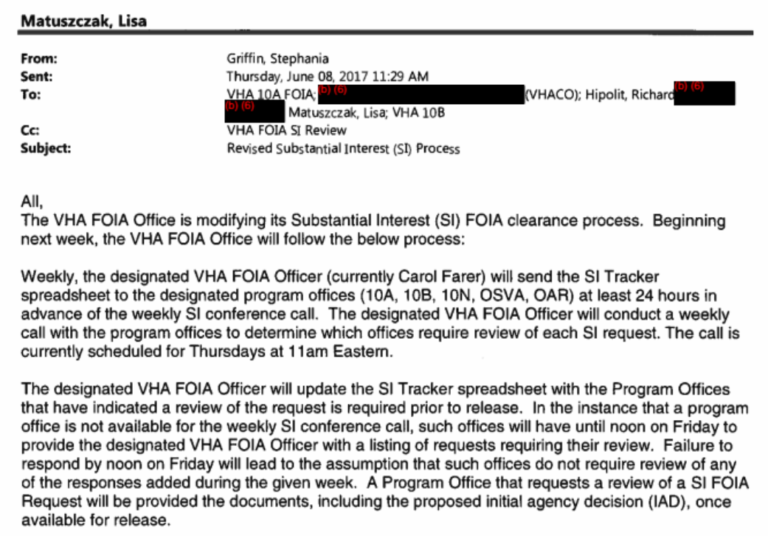

It is more difficult to gauge how sensitive review has continued to develop at the VA. CoA Institute has filed four separate administrative appeals on its original FOIA request seeking records about the practice, but the agency has been slow to produce anything from the past few years. But the few records obtained by CoA Institute nevertheless suggest that “sensitive review” remains in place. Indeed, an especially revealing email from June 2017 confirms that the VA maintains a “Substantial Interest (SI) FOIA clearance process.” The agency schedules weekly conference calls about “sensitive” requests and circulates weekly reports with tracking spreadsheets. These developments show that the VA’s sensitive review process has been systematized and become a regular part of FOIA administration in the Trump Administration.

Although the “substantial interest” review process is not supposed to take “more than a week”—and is for “situational awareness” purposes only—agency components are still expected to provide copies of responsive records for departmental-level review. And the failure of the front FOIA office to act on a request, or to provide feedback, can lead to a further delay on a “case by case” basis. That seems to contradict information found in a September 2018 VA training presentation, which suggested that sensitive review is not intended to “impact any processing or release of responsive records.” Unfortunately, based on the best publicly available information, sensitive review at the VA seems as problematic as ever.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute