We recently began our series of blog posts examining the history, purpose, and limitations of the Antiquities Act of 1906, 54 U.S.C. §§ 320301 – 320303 (“Antiquities Act” or the “Act”). Today we continue discussing how the Act fits within the variety of other frameworks for protecting and using public lands. So what is the Antiquities Act?

In contrast to the Act’s ambiguous status, as discussed yesterday, the land management plans that arise from statutory schemes, and which are managed by the administrative agencies, are both comprehensive and detailed. The United States federal government owns approximately 640 million acres of land.[1] Of that, just over 610 million acres, or 95% of federally owned lands, are under the control of one of the four main federal land management agencies: The Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”), the Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, or, the Forest Service. The first three of these agencies are part of the Department of Interior (“DOI”), while the last is part of the Department of Agriculture. Federal public lands are administered subject to “a myriad of individual agency mandates to manage particular lands and particular resources” overlapped by “general environmental statutes.”[2] In addition, these agencies hold full or co-management responsibilities for all the national monuments.

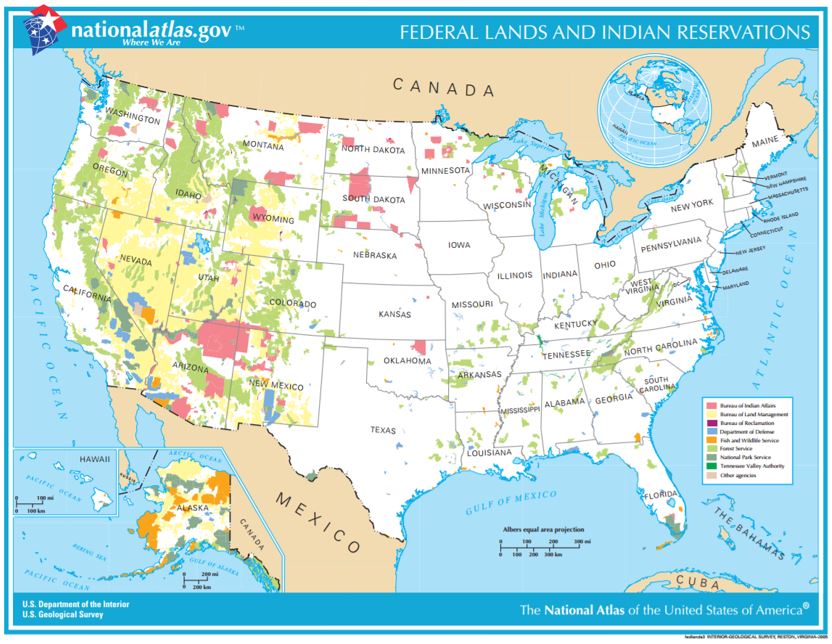

The map below shows the extent of federally held lands in the United States:

Source: U.S. Geological Survey

Established in 1905, the Forest Service is the oldest of the four major federal land management agencies, and the only one to officially predate the passage of the Antiquities Act. Its mission is “to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations.” The National Park Service followed over a decade later in 1916 and has a dual mission to preserve natural and cultural resources and provide such for the enjoyment of the public. The BLM, founded in 1946, is charged with the “stewardship of our public lands” and its management of such lands is “based upon the principles of multiple use and sustained yield of our Nation’s resources within the framework of environmental responsibility and scientific technology.” In 1966, Fish & Wildlife was the last of these agencies to be established and was tasked with “working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people.”

Read together, the missions of these federal public lands management agencies are to work collaboratively with numerous stakeholders to conserve and protect the nation’s natural and cultural resources with an eye towards multiple use and sustainable processes, as well as public access. The Antiquities Act is at odds with these major public lands management agencies to the extent that designations are made at the sole discretion of the President without consideration of existing land management, historic preservation, and/or environmental protection plans, and without any need for public input.

In addition to the laws providing for historic preservation, there are no less than twenty federal laws providing for the designation, protection, and management of environmentally sensitive areas located on public lands.[3] Many of those laws, such as the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (“FLPMA”) and the National Environmental Policy Act (“NEPA”), require both public input and environmental assessments as part of their planning processes, which the Antiquities Act does not.

Although NEPA and FLPMA may be included in the final management plans for individual monuments, there is no affirmative requirement under the Antiquities Act to provide for environmental protections on the declared parcels. Curiously, some proponents of using the Antiquities Act have supported this aspect of the law because, in their view, bypassing congressional consensus or environmental review is a quicker and easier way to gain land protections. This perceived expediency and ease of using the Antiquities Act is no replacement for open and transparent discourse, particularly considering existing comprehensive historic preservation, land management, and environmental statutory and regulatory schemes that have established mechanisms for public and congressional oversight and input.

Given the hybrid nature the Antiquities Act and the sometimes arbitrary nature of its use, any reforms, if made, should consider existing statutory and regulatory frameworks for historic preservation, public lands management, and environmental protection, as well as methods for strengthening transparency and government accountability in decision-making.

Our series will continue next week with an overview of the environmental and fishery management laws that relate to marine or other water-based federal territories.

Any questions, commentary, or criticisms? Please e-mail us at kara.mckenna@causeofaction.org and/or cynthia.crawford@causeofaction.org

Cynthia F. Crawford is a Senior Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.

Kara E. McKenna is a Counsel at Cause of Action Institute. You can follow her on Twitter @Kara_McK

a[1] Cong. Research Serv., Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data (Mar. 3, 2017).

[2] Marla Mansfield, A Primer of Public Land Law, 68 Wash. L. Rev. 801, 802 (1993).

[3] See e.g., Organic Act of 1897; Transfer Act of 1905; National Park Service Organic Act; Fish and Wildlife Act of 1956; Archaeological Recovery Act of 1960; Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960; Wilderness Act of 1964; National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act of 1966; The National Historic Preservation Act; Wild and Scenic Rivers Act; National Trails System Act of 1968; Mining and Minerals Policy Act of 1970; Endangered Species Act of 1973; The Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971; National Forest Management Act of 1977; Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977; Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979; Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act of 1980; Federal Cave Resources Protection Act of 1988; National Landscape Conservation System.