On October 9, 2019, the White House issued two executive orders designed to curtail the abuse of guidance documents by government agencies. Both orders address due process violations by agencies by requiring notice and an opportunity to be heard before action can be taken or liability imposed against alleged wrongdoers. Learn More

Federal judge rejects DOJ’s use of attorney-client, deliberative process privileges to hide communications with the White House Counsel from public disclosure

Judge James Boasberg of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia yesterday granted in part Cause of Action Institute’s (“CoA Institute’s) motion for summary judgment in a Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) lawsuit against the Department of Justice (“DOJ”). Judge Boasberg vigorously rejected DOJ’s attempt to withhold records of communications with the White House under the attorney-client and deliberative process privileges. CoA Institute filed its lawsuit in July 2017, after DOJ refused to produce records that would have revealed whether it was involved in implementing a controversial directive from the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services. The underlying request at issue, which CoA Institute submitted in May 2017, followed reports that Jeb Hensarling, Chairman of the Financial Services Committee, had directed twelve agencies—including, the Department of the Treasury and eleven other entities—to treat all records exchanged with his Committee as “congressional records” not subject to the FOIA.

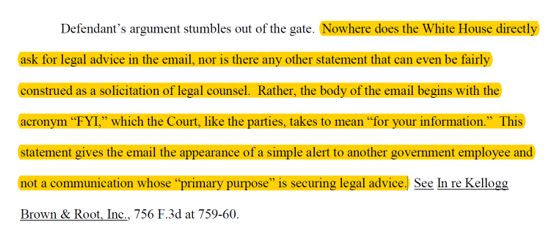

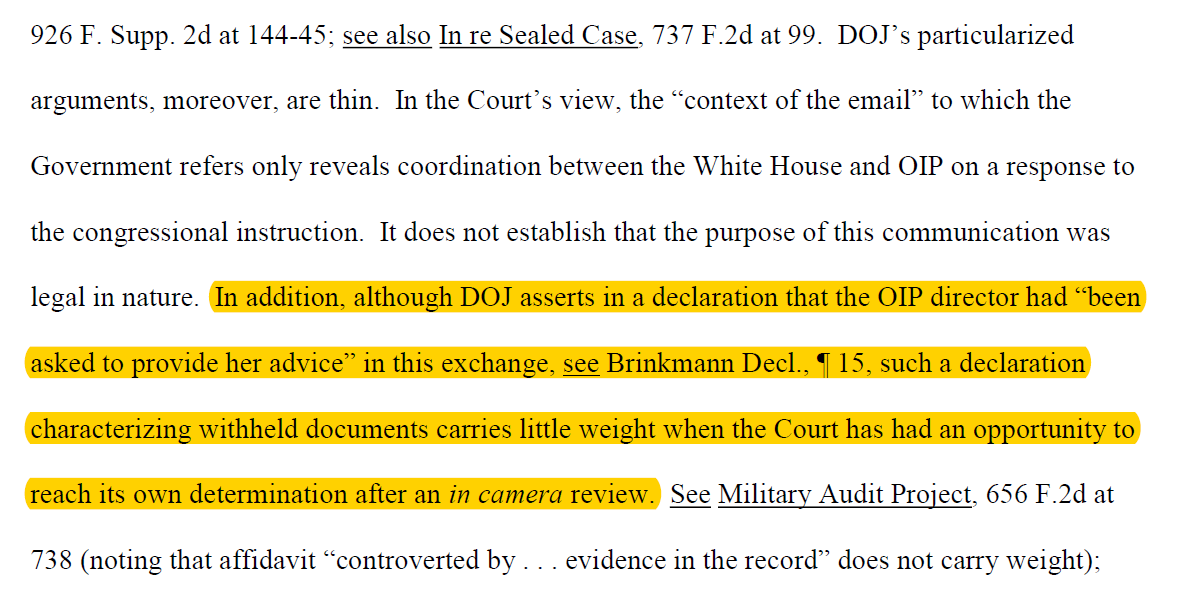

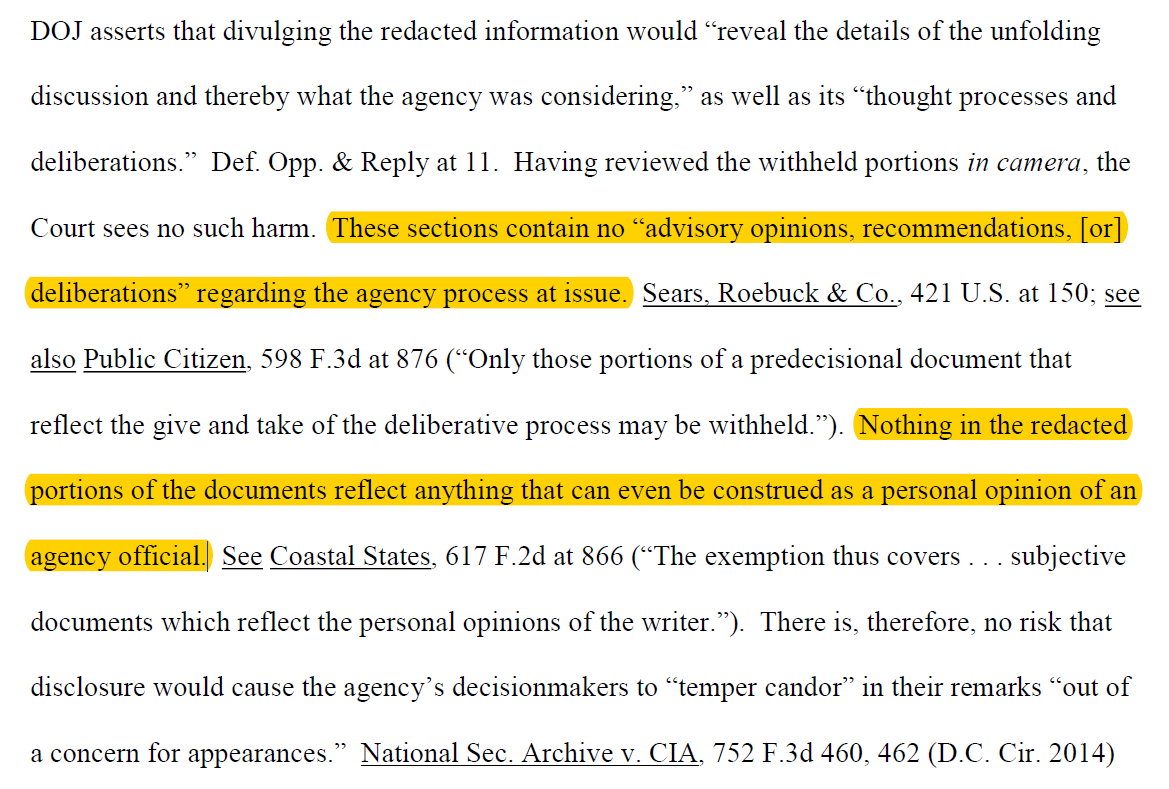

Judge Boasberg’s most damning holding concerned DOJ’s misuse of Exemption 5 to redact a line from a White House email and to withhold in full an attachment—presumably the letter from Chairman Hensarling—received by several Executive Branch agencies. As the Court explained:

Indeed, any reasonable individual would reach the same conclusion as the Court after cursorily examining the record at issue.

The sole basis of DOJ’s defense was the declaration a senior agency attorney, who claimed that the White House email reflected a “routine” sort of “consultative exchange” in which Office of Information Policy Director Melanie Pustay was asked for “advice.” But the Court saw through this self-serving statement and explained that DOJ had failed to meet its burden in proving that the specific record at issue reflected the provision of legal services. To rule otherwise would tend to turn any correspondence with a government attorney into privileged material.

The Court also failed to see how the withheld material contained any confidential information. For example, the attachment to the White House email—ostensibly, a copy of the Hensarling letter—was merely one of many substantively identical letters that DOJ admitted were received across the Administration. There was simply no agency-specific confidential information at issue.

Judge Boasberg further rejected DOJ’s use of the deliberative process to withhold the same White House communications. Despite the government’s arguments during briefing, after reviewing the records itself, the Court determined that they contained nothing that could be construed as deliberative.

Although the court granted in part CoA Institute’s motion, it also sided with the government over the withholding of eleven pages of records exchanged between DOJ and an unidentified agency. After reviewing those records, the Court determined that they did, in fact, reflect the agency’s decision-making processes and revealed the solicitation and provision of confidential legal advice. Moreover, there were no reasonably segregable portions of the records that could be released to CoA Institute. Finally, the court did not resolve the parties’ dispute over the “foreseeable harm” standard that Congress introduced in the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016..

* * *

The Court has ordered DOJ to release unredacted versions of the White House communications. Once these records have been released, we will provide another update addressing their contents.

Judge Boasberg’s opinion is available here.

Ryan Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute

Loading...

Loading...

Department of the Army Refuses to Search Its Servers for Email Records

In May 2016, Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) sued the Department of the Army after it refused to produce records under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) concerning the use of teleconference technology at the White House. CoA Institute’s FOIA request, which was filed in June 2015, followed the release of a record in an unrelated FOIA matter by the Office of Management and Budget (“OMB”). That email revealed how a special email account, “system.manager@conus.army.mil,” had been set-up and was operated by the military for the purposes of facilitating teleconferences.

Although the OMB record may strike some as containing seemingly benign information, it nonetheless piqued our interest. We realized that little is known about how the Executive Office of the President (“EOP”) arranges its audio and video conferences. Moreover, there is scant public information available about the important role played by the President’s “IT team,” the White House Communications Agency (“WHCA”), in the functioning of the White House. We were also troubled because the OMB record showed how WHCA was responsible for facilitating a conference call for inter-agency consultation on “White House equities.” As we have repeatedly described, “White House equities” review is a form of FOIA politicization that allows the President to interfere with and delay the production of politically sensitive records.

WHCA released approximately 200 pages of email correspondence in response to our request. The Army, however, failed to identify any responsive records. In the lead up to summary judgment proceedings, we continually asked the Army about its efforts to search for records in the “@conus.army.mil” account. We had even given the Army a copy of the OMB email when we filed an administrative appeal in September 2015. But the Army kept mum and only provided details about its “search” last month, arguing that it had located the so-called CONUS account and determined that its contents were stored on Army computer servers. But the Army claimed that the account would contain zero “responsive records.” Why? Because only “EOP personnel” interfaced with the account, even though it was owned and maintained by the military and stored on Army hardware.

We filed our own cross-motion for summary judgment yesterday. The first part of our argument focuses on the Army’s unjustifiably narrow and unfair reading of our FOIA request, which sought all records of correspondence with EOP about conference calls “hosted and/or arranged by the military.” Not only did we give the OMB record to the government to demonstrate exactly the sort of records we wanted—which should be enough to defeat the Army’s interpretation of the scope of our FOIA request—but any natural reading of the operative words “hosted” and “arranged” would include the situation of an agency maintaining a software system and email account for the sole purpose of setting-up audio and video conferences. Whether Army personnel were involved in the day-to-day business of confirming the details for a new conference, or merely set up some sort of automated process, is without moment.

The second part of our cross-motion concerns the redaction of non-contractor employees of the Department of Defense (“DOD”) in the WHCA correspondence. DOD takes the position that, as a categorical matter, nearly all the names and email addresses of its employees may be kept secret. But there are several problems with this position. First, FOIA caselaw generally disfavors categorical claims and, in the context of personal privacy interests, the public interest can outweigh an individual’s right to keep their name and work information secret—particularly when the individual is a government employee. Second, official DOD policy posted on the agency’s FOIA website explicitly directs the sort of information we want to be made public unless disclosure would raise “substantial security or privacy concerns.” Finally, the FOIA’s newly-added “foreseeable harm” standard mandates that an agency demonstrate how specific pieces of information may, if disclosed, be reasonably foreseen to harm an interest protected by a statutory exemption. That sets a high bar, particularly in the context of DOD’s categorical and generally applicable policy. In this case, it seems unlikely that the EOP’s IT staff could be described as working in a “sensitive” position, akin to activity duty military personnel on the front line or law enforcement officials involved with criminal investigative activities. We look forward to the Army’s reply brief.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.

Litigation Update: Cause of Action v. Department of Justice and the House Financial Services Committee’s Attempt to Undermine the FOIA

In July 2017, Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) sued the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) after the agency refused to produce records under the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) that would have revealed whether the Office of Information Policy (“OIP”) or Office of Legislative Affairs (“OLA”) were involved in implementing a controversial directive from the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services. CoA Institute’s FOIA request, which was filed in May 2017, followed reports that Jeb Hensarling, Chairman of the Financial Services Committee, directed twelve agencies—including, the Department of the Treasury and eleven other entities—to treat all records exchanged with the Committee as “congressional records” not subject to the FOIA.

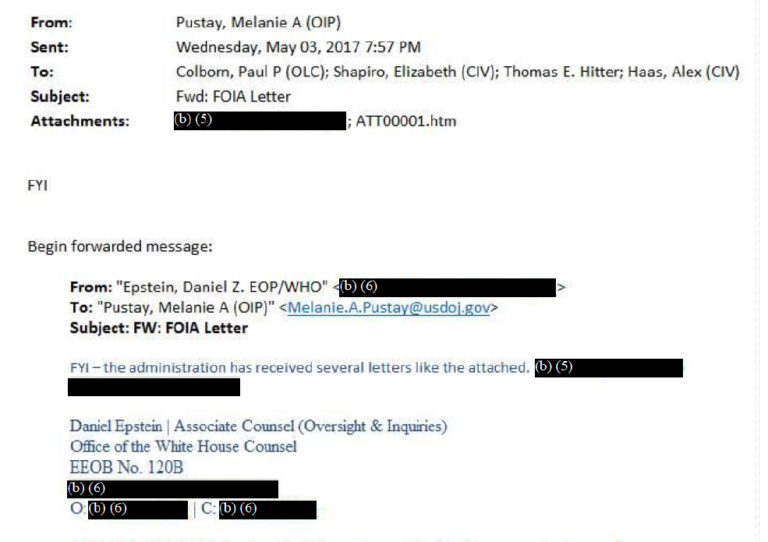

As a result of litigation, DOJ identified sixteen pages of responsive records. Eleven pages, which represent communications between an “unidentified Executive Branch agency” and DOJ, were withheld in full. One additional record—an email between the Office of the White House Counsel and OIP—was partially redacted, but an attachment—a copy of Chairman Hensarling’s letter—was withheld in full. DOJ defended its treatment of these records by invoking the attorney-client and deliberative process privileges.

Last Friday, CoA Institute moved for summary judgment, rebutting DOJ’s claims and arguing that the agency could not use the attorney-client and deliberative process privileges. With respect to the White House email and attachment, DOJ failed to establish that an attorney-client relationship existed between the White House Counsel and OIP. Assuming the requisite relationship did exist, the email still neither revealed private confidences nor solicited legal advice. It also did not reflect a deliberative or consultative process. Instead, the email was a literal “FYI”—the sort of informational notice that courts regularly compel agencies to disclose:

DOJ also wrongly withheld the email attachment—a copy of Chairman Hensarling’s letter—because the letter is already in the public domain and, in any case, does not reveal confidential information pertaining to the White House or DOJ.

Communications with the “unidentified Executive Branch agency” similarly cannot be exempt under the attorney-client and deliberative process privileges. Although these records may contain legal advice on responding to Chairman Hensarling’s directive, they were shared outside of the Office of Legal Counsel, which is the DOJ component responsible for providing legal opinions to the White House and the rest of the Executive Branch. To maintain attorney-client confidentiality, an agency must not circulate privileged material beyond those officials tasked with providing (or receiving) legal counsel. Here, by involving OLA, which functions as DOJ’s congressional affairs office and does not serve as an “attorney” to other agencies, the “unidentified” agency waived any expectation of confidentiality. Finally, DOJ misused the deliberative process privilege because it failed to explain how these inter-agency communications reflected DOJ’s recommendations or opinions or were otherwise non-factual.

Importantly, DOJ also failed to meet its burden under the new “foreseeable harm” standard. Congress introduced this standard with the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016 to codify the so-called “presumption of openness,” which discouraged the mere “technical” application of exemptions. The FOIA, as amended, now requires an agency, such as DOJ, to explain how specific records can reasonably be foreseen to harm agency interests. DOJ failed to provide a satisfactory argument in this case and did not even mention its obligations under the new standard.

* * *

The public deserves to know how, and to what extent, DOJ was involved in formulating and implementing Chairman Hensarling’s anti-transparency policy. Because Congress is not itself subject to the FOIA, a request for records that have been exchanged with the legislative branch presents unique difficulties. Nevertheless, the law requires that Congress manifest a clear intent to maintain control over specific records to keep them out of reach of public disclosure. As I have argued previously, Chairman Hensarling’s directive is ineffective in this respect. The mere fact that an agency possesses a record that relates to Congress, was created by Congress, or was transmitted to Congress, does not, by itself, render it a “congressional record.” Any deviation from this acknowledged standard for defining a “congressional record” would frustrate the FOIA and impede transparent government.

The real-world implications of these sorts of congressional anti-transparency efforts are hardly imaginary or speculative. The House Financial Services Committee has already intervened in a FOIA lawsuit to enforce its directive. (That lawsuit is still ongoing.) And CoA Institute is involved with a lawsuit against the Internal Revenue Service that involves a similarly overbroad effort by the Joint Committee on Taxation to sweep a range of agency records outside the scope of the FOIA. CoA Institute has twice joined with other good government groups to express concern over these developments (here and here). We are hopeful that the courts will put a stop to Congress’s games, and ensure public access to vital records revealing the interaction of the administrative state with the federal legislature.

CoA Institute’s brief is available here.

Ryan Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute

IRS Dodges Oversight, Refuses to Measure Economic Impact of its Rules: Investigative Report

Washington D.C. – Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) today released a groundbreaking investigative report, Evading Oversight: The Origins and Implications of the IRS Claim that its Rules Do Not Have an Economic Impact, that reveals how the IRS has developed a series of self-bestowed exemptions allowing the agency to evade several legally required oversight mechanisms. The report outlines in detail how the IRS created this exemption to exempt itself from three critical reviews intended to provide our elected branches and the public an opportunity to assess the economic impact of rules before they are finalized.

Read about the report in today’s Wall Street Journal, including suggestions for how the White House and Congress can work together to end this harmful practice.

CoA Institute Counsel and Senior Policy Advisor James Valvo: “The IRS for too long has evaded its responsibilities to conduct and publish analysis of its rules. Rules issued by the IRS can change the economic landscape for Americans in many ways, including how the agency calculates deductions, exemptions, reporting, and recordkeeping. By creating bureaucratic loopholes, the IRS deliberately sidesteps several oversight mechanisms designed to provide a check on overly burdensome rules. The IRS should be held to the same standard as other regulatory agencies and stop avoiding its responsibilities.”

For years, the IRS has evaded several laws directing agencies to create economic impact statements for rules. These analyses are part of three oversight mechanisms: The Regulatory Flexibility Act, the Congressional Review Act, and review by the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. All three are good-government measures designed to provide a check on abuse by the administrative state.

CoA Institute’s investigative report reveals the origins and implications of the unprecedented IRS position that its rules have no economic impact and do not require such analysis because, it claims, any impact emerges from the underlying law that authorized the rule, and not the agency’s decision to issue or alter it.

The full report, including executive summary and key findings, can be accessed HERE.

For information regarding this press release, please contact Zachary Kurz, Director of Communications at CoA Institute: zachary.kurz@causeofaction.org.

The Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program

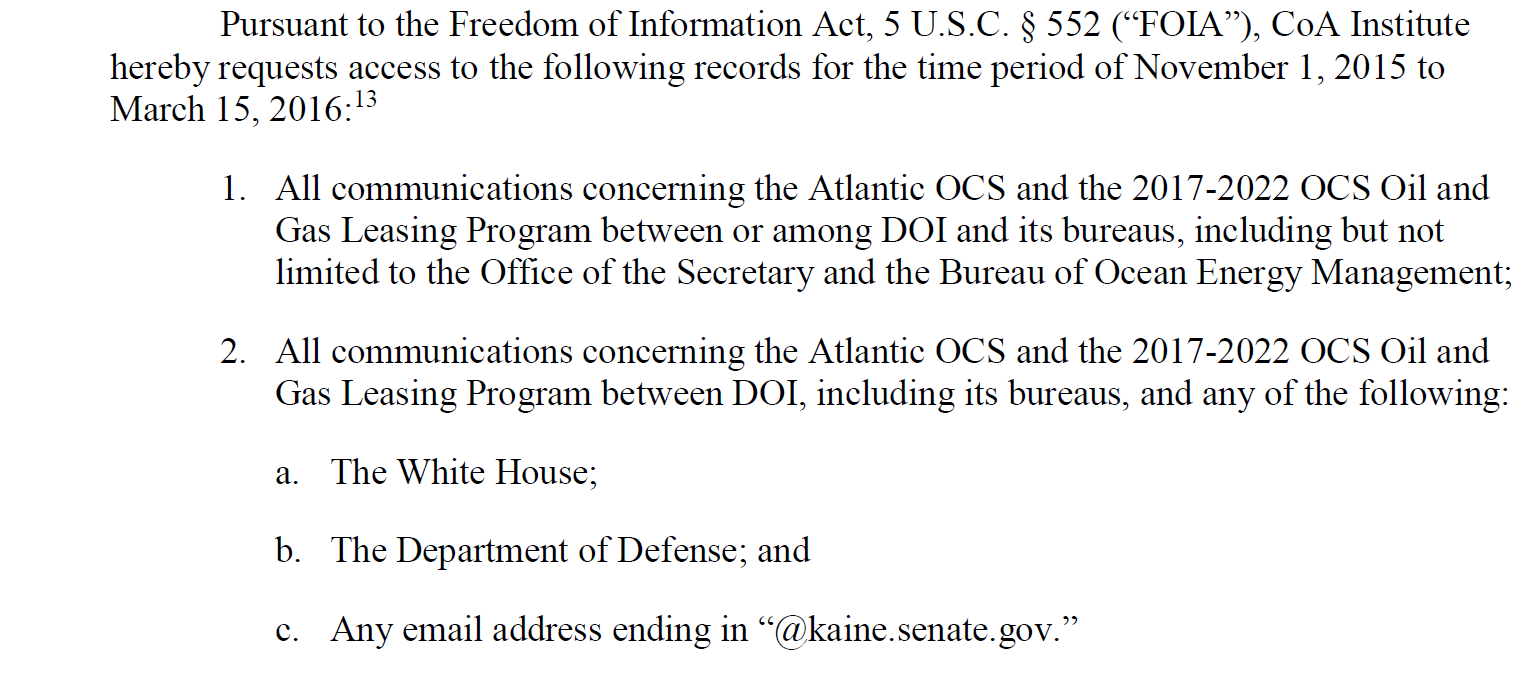

In August of 2016, Cause of Action Institute (“CoA Institute”) submitted a Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) request, seeking the following information about the Outer Continental Shelf (“OCS”):

Because of the agency’s failure to release records responsive to this request, CoA Institute filed a FOIA lawsuit on November 11, 2016. Recently, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (“BOEM”) provided its 10th and final production. While CoA Institute is still in active litigation regarding this request, considering the new administration and its priorities, we thought it of value to discuss our findings to date. However, to fully understand the process, we believe that some background on the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (“OCSLA”), 43 U.S.C., is necessary.

The Outer Continental Shelf and OCSLA background

The outer continental shelf is made up of “all submerged lands lying seaward and outside of the area of lands beneath navigable waters…and of which the subsoil and seabed appertain to the United States and are subject to its jurisdiction and control.” OCSLA was enacted on August 7, 1953 and governs the policies and procedures related to the OCS. Under OCSLA, the Secretary of Interior (the “Secretary”) is responsible for the administration of mineral exploration as well as other OCS development (i.e., wind energy).[1] Further, through OCSLA, the Secretary may grant leases to the highest qualified responsible bidder based on sealed competitive bids.[2] OCSLA also provides guidelines for implementing an OCS oil and gas exploration and development program.[3] This program, the Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program, is commonly referred to as the “Five-Year Program”.

Specifications under the Five-Year Program

As provided in the OCSLA, the Five-Year Program shall have a schedule that indicates as precisely as possible, the size, timing and location of leasing activity best suited for national energy needs during the five-year period following its approval or re-approval.[4] In reviewing the five-year program, the BOEM looks at a variety of economic and environmental factors. The timing and location of exploration, development, and production of oil and gas on the OCS shall be based on consideration of eight factors.

These factors are:

“(A) existing information concerning the geographical, geological, and ecological characteristics of such regions; (B) an equitable sharing of developmental benefits and environmental risks among the various regions; (C) the location of such regions with respect to, and the relative needs of, regional and national energy markets; (D) the location of such regions with respect to other uses of the sea and seabed, including fisheries, navigation, existing or proposed sea-lanes, potential sites of Deepwater ports, and other anticipated uses of the resources and space of the outer Continental Shelf; (E) the interest of potential oil and gas producers in the development of oil and gas resources as indicated by exploration or nomination; (F) laws, goals, and policies of affected States which have been specifically identified by the Governors of such States as relevant matters for the Secretary’s consideration; (G) the relative environmental sensitivity and marine productivity of different areas of the outer Continental Shelf; and (H) relevant environmental and predictive information for different areas of the outer Continental Shelf.”

Further, the Five-Year Program provides that the Secretary shall request and contemplate input from federal agencies and the Governor of any State that could be affected under the proposed leasing program. Suggestions from local government executives in states that may be affected, which have been previously mentioned to the Governor of such State and any other person may also be considered. Under 43 U.S.C. §1331, the term “person” includes, in addition to a natural person, an association, a State, a political subdivision of a State, or a private, public, or municipal corporation.

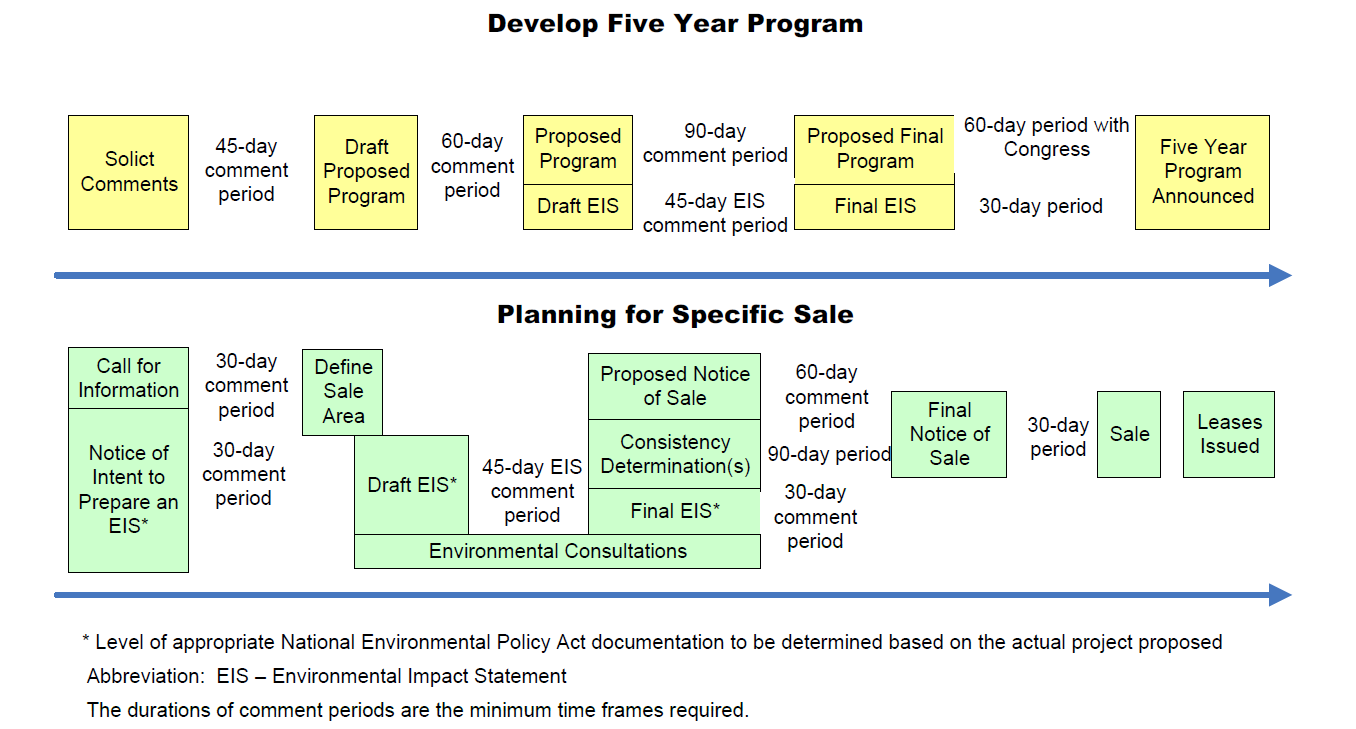

The Five-Year Program “process includes three separate comment periods, two separate draft proposals, a final draft proposal, a final secretarial proposal, and development of environmental impact statement (EIS).” This process, takes approximately two and a half years to complete. As mentioned above, input from federal agencies, state and local government, and any other person, may be considered. After the Secretary approves the program, the Proposed Final Five-Year Program is sent to the President and Congress. After at least sixty days, the Secretary may approve the program. The Department of Interior cannot offer an area for lease without it being included in an approved Five-Year Program.

The Secretary shall review the leasing program approved under this section at least once a year. After Secretarial approval, the geographic scope of a lease sale area can be narrowed, cancelled, or delayed without the development of a new program. The Secretary shall, by regulation, establish procedures for various steps in the management process. Such procedures will apply to various activities, including any significant revision or reapproval of the leasing program.

This series will continue next week with a comparison between the requirements outlined above and the process that took place during the 2017-2022 planning process.

Any questions, commentary, or criticisms? Please email us at kara.mckenna@causeofaction.org and/or katie.parr@causeofaction.org

Katie Parr is a law clerk and Kara E. McKenna is a counsel at Cause of Action Institute.

[1] Bureau of Energy Management, BOEM, https://www.boem.gov/OCS-Lands-Act-History/ (last visited January 3, 2018).

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

President Trump to appoint a new watchdog for the Intelligence Community

As we have argued previously, one of the most troubling aspects of President Obama’s legacy was his failure to nominate permanent Inspectors General (“IGs”) at many agencies across the federal government. Without presidentially-appointed, Senate-confirmed leadership, there is always a real danger that IG offices will lack the necessary commitment to transparency and accountability in government. As Senator Ron Johnson has commented, “acting” IGs—who are typically career civil servants—risk being “not truly independent [because] they can be removed by the agency at any time; they are only temporary and do not drive office policy; and they are at greater risk of compromising their work to appease the agency or the president.”

When President Obama left office, twelve agencies lacked an IG. Since taking office, President Trump has steadily moved to remedy this dearth of leadership. Last month, we praised the President for nominating five individuals to some of these watchdog vacancies. Now, we can sound another note of accomplishment following the White House’s announcement today that it intends to name Michael Atkinson as Inspector General of the Intelligence Community. Although this post only became vacant shortly after President Trump took office—the former IG, Charles McCullough, retired in March 2017—it is a vital one, particularly in the current political climate. Mr. Atkinson, who studied law at Cornell University, currently serves as the Acting Deputy Assistant Attorney General for the Department of Justice’s National Security Division. He previously worked in the Department’s Fraud and Public Corruption Section.

We reiterate our hope that the White House will continue its efforts to find IGs for all current vacancies, such as those at the Department of Defense, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The Department of the Interior, sadly, continues to lack a permanent IG since the previous watchdog left office 3,175 day ago. These large agencies have substantial budgets, and presidentially-appointed IGs will provide an important internal check on waste, fraud, and abuse.

Ryan P. Mulvey is Counsel at Cause of Action Institute.